1918 is notable not only for marking the end of the First World War but also for being the year when the world was faced with one of the most deadly pandemics it had ever experienced. Where it came from is uncertain although it did not come from Spain despite its popular name of Spanish ‘flu, coined because it was through the uncensored press of neutral Spain that others first became aware of it. Of the theories put forward, the most generally accepted is that it developed in the military population due to wartime conditions, in particular, where humans and animals such as pigs, horses and poultry, live in close proximity.1 These conditions were common in Military camps like Etaples in France, and provided the influenza A virus, the type capable of infecting animals as well as humans and causing epidemics and pandemics, with the perfect environment to jump species and mutate into a strain against which humans had no resistance. The type A strain which caused the 1918-19 pandemic is now known to be H1N1.

The pandemic appeared first in naval and military populations in April 1918, infecting the British Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow, the American and British Expeditionary Forces in France and the German Army. As men returned home on leave, they took the infection with them. Thus, it entered the civilian population, first through the ports and then, by means of the main communication routes such as railway lines, into towns and cities along the way, from where human contact carried it into all the remaining towns, villages and rural areas across the country.

In Britain, the pandemic occurred in three waves over 46 weeks which, according to the official report by the Registrar-General for England and Wales (R-G), published in 1920, were between 23 June 1918 and 10 May 1919.2 The report places the first or summer wave from 23 June to 14 September 1918, the second or autumn wave from 15 September 1918 to 25 January 1919 and the third or spring wave from 26 January to 10 May 1919, although onset, duration and severity of each wave differed from place to place.

The unseasonable appearance of the first wave of influenza in the summer months made this an unusual event to begin with. It was also extremely contagious and many people, especially school children, became infected although most recovered. The second wave, however, was much more serious. The speed with which it struck its victims, the virulence of the infection and the fatal consequences which often ensued, made this wave particularly lethal, while the third wave was only slightly less severe. Furthermore, the age range most seriously affected by it, the 18 to 40 year olds, should have been most resistant to its effects which added to the unexpected nature of the disease.

A prominent feature of this influenza outbreak was the heliotrope cyanosis or purplish-blue discolouration of the faces of victims, signalling a lack of oxygen to the body and approaching death. This was caused by pneumonic complications associated with additional bacterial infection in the lungs; post mortem examinations revealing lungs full of bloody fluid, indicating that the patient had effectively drowned. This was caused by the over-reaction of the victim’s immune system to the virus, the most aggressive response being made by the systems of healthy young adults, hence their susceptibility.

News that the pandemic had reached Nottinghamshire and that there were ‘many hundreds of cases’ appeared in the East Midlands’ press in July 1918.3 Four days later Nottingham Post Office and the Corporation Tramways were reported as experiencing serious difficulties in maintaining services through staff illness.4 School children were particularly affected by the infection and elementary schools were closed in Sutton-in-Ashfield because of absences. Factory workers and miners were also badly affected, 250 miners being reported absent from the Mansfield pit in one day.5 By August the outbreak seemed to be over but this was just the end of the first wave. When the second wave appeared it was much worse.

The second wave struck the military population in August 1918 and mortality rose significantly. It appeared in Nottinghamshire in October and a severe social and medical crisis quickly ensued. Businesses, such as ‘the Nottingham and Notts Bank in Thurland Street’ and ‘the Netherfield Co-operative Society’ struggled to cope because of staff illness and absenteeism.6 In Industry, Nottinghamshire miners in the Bulwell, Annesley and Newstead districts were reported as suffering badly,7 while in Arnold the press revealed that ‘Hundreds of men and women are away from work and some of the factories have been almost deserted.8

Public services were also seriously disrupted once again. The local press reported that ‘50 per cent of telephonists…in the Nottingham district …’ were down with influenza,9 while at the Nottingham Summons Court numerous cases had to be adjourned because of illness.10 Nottingham authorities were reluctant to close schools but following a serious increase in the death rate in the city in November, the Education Committee decided to close schools immediately, not re-opening them until 16 December.11

Dr Philip Boobbyer

In matters of public health and the control of epidemic disease, the Local Government Board (LGB) was the central authority responsible, but local health authorities in the guise of Sanitary Committees and their Medical Officers of Health (MOH), were by far the most active in this respect. The MOH for Nottingham was Dr Philip Boobbyer who, in a possibly unique measure in England, set up an emergency influenza hospital in what had been a war crèche at Annesley House in Queen’s walk, where the principal treatment was fresh air and plenty of it. In addition, he set aside 36 beds for influenza patients in Bagthorpe Isolation Hospital where he was medical superintendent.

Nonetheless, care of the sick was a serious problem as 52 per cent of doctors, thousands of nurses and the majority of hospital facilities had been taken over by military authorities, leaving little for sick civilians.12 Where hospitals, like Nottingham General Hospital, were willing and able to take influenza victims, the usual procedure was to set aside wards but these quickly became full. Consequently, most people had to be cared for at home which caused great difficulty for the general practitioners and nurses still remaining in civilian practice.

Dr Boobbyer admitted that ‘Some doctors have not had their clothes off for two or three days…Several doctors have over 200 patients on their lists.’13 One Nottingham doctor who had to suspend his morning surgery to visit influenza victims devised a system by which he left prepared medication at his practice and patients would call in and collect it.14

The extreme circumstances in which doctors found themselves is indicated by a desperate plea sent by one general practitioner in Nottingham to the War Cabinet.

I beg to represent, as a matter of the gravest and most immediate urgency the necessity for the demobilisation of men from the army to help the local profession...We at the clinic are carrying over 40 and 50 patients…from one day’s waiting list to the next. Cases are being left for days unvisited…and the unvisited cases may any of them be pneumonia or even of more urgent consequences, yet it is physically impossible to cover the ground. I am personally extremely near the limit of my physical endurance, after working for a long period from 14 to 18 hours (or more occasionally) Sundays and week-days. Meantime we are all grossly misused and our patients are literally being neglected and unattended…15

The difficulty of acquiring the services of a doctor coupled with the speed and suddenness with which many people died from the infection resulted in a significant increase in coroners’ inquests. Nottingham press reported:

During the weekend the ‘flu has exacted another heavy toll from the inhabitants of the Nottingham district and both the city and the county coroners this morning received further batches of reports of cases where the victim of this extraordinary malady had passed away so suddenly that it was impossible to obtain medical aid.

The city coroner has no fewer than 14 of these cases under consideration, whilst the county coroner has also received a number of reports of tragically sudden deaths from the ‘flu at Gedling, West Bridgford, Eastwood and other parts of the district.16

Unfortunately, the release of medical personnel from military service was slow. However, Dr Boobbyer devised a strategy to aid hard-pressed doctors. He closed the maternity and infant welfare centres in the city and took their entire staffs, totalling 16 nurses, and assigned them to doctors working in the community. These nurses visited all cases of influenza as soon as doctors were notified; they reported back on the condition of the patient then took charge of the less serious influenza cases, allowing doctors to concentrate on the serious ones. By this means, it was reported, ‘excellent results are being obtained.’17

So effective was this measure that Dr Boobbyer received high praise from the LGB. One of their medical experts, a Colonel James, visited him in Nottingham and said that ‘Without this assistance the medical services of the city must have broken down badly.18 It was a measure also employed by Dr Parkinson, MOH for Basford Rural District Council who engaged 4 nurses at a cost of 14 guineas to undertake similar work and it was reported as being ‘money well spent.’19

This highlights that the most urgent need of influenza patients was nursing care. In fact, doctors had no idea what treatment to give; some resorting to ancient practices such as cupping and blood-letting or smoking pipes full of strong tobacco whilst treating patients in the belief that this was a powerful germicide. The most commonly prescribed ‘medicine’ was alcohol, particularly whiskey and brandy, but this was very difficult to obtain during war time. Consequently, nursing care did much more good than anything that doctors were doing at that time.

In a press interview in October 1918, Sir Arthur Newsholme of the LGB advised anyone infected to go immediately to bed and stay there until recovered.20 This was followed by a circular to local authorities to publicise, giving a list of things for the public to do to prevent the spread of infection. This advised: the constant flushing of rooms with fresh air; avoidance of overcrowded rooms and places of entertainment; one person to one room for sleeping purposes in infected homes; wet cleansing of all infected areas; abstention from indiscriminate spitting, alcoholism, prolonged mental strain and over fatigue; all catarrhal attacks and illness involving raised temperatures to be regarded as infectious and precautionary measures adopted.21 Dr Boobbyer also added the importance of boiling all eating utensils used by others before using them oneself.

Item two on the LGB list reveals the concern felt by public health authorities on the danger of crowded environments spreading infection and in November 1918 the LGB issued an order concerning the restriction of performances in cinemas, theatres and music halls and the ventilation of such premises, action which had already been taken by many local authorities.

Picture House advert

Some establishments advertised in the local press to reassure patrons that their houses were free of influenza germs. For example, the proprietors of the Picture House in Long Row, Nottingham stated that they had spent thousands of pounds installing a perfect ventilation system which was ‘an absolute victory over impure atmosphere’22 The restrictions agreed in Nottingham were similar to those operating elsewhere. These were: children under 14 years barred from entry; no performances between 5.00pm and 6.00pm each day to allow doors and windows to be opened for thorough ventilation; a further period of ventilation for 10 minutes between the hours of 8.00pm and 9.00pm. Following a military order on 19 November 1918, uniformed personnel, including nurses, were also barred from entry.

With no National Health Service and with doctor’s fees beyond the means of many people, self -medication was the usual way to deal with illness at this time and although medical care was provided freely to those in need during the crisis, people still purchased over-the-counter remedies for curing or preventing influenza. Some of these were nutritional products, some focused on hygiene and others were intended for use as medicines.

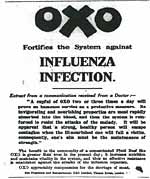

Advert for OXO

Poor nutrition, especially a lack of meat, was thought by some to be the cause of the influenza outbreak. Consequently, products such as OXO, Bovril and Chymol were advertised as the solution, strengthening the system against infection and aiding recovery.23 For cleansing purposes, carbolic soap was favoured, particularly Lifebuoy, Gossages and Pinkobolic soaps.24 Medicinal products included Venos Lightening Cough Cure, Formamint Throat Tablets, Dr William’s Pink Pills, Collenza, Dr Mayu’s Influenzine, Fort-Reviver and Ker-Nak Tablets, while Boots eau de cologne was advertised as an antiseptic perfume.25 Furthermore, some doctors encouraged the use of a nose and mouth wash made from a solution of permanganate of potash and salt, as well as smoking as a germicide.26 A more unusual remedy was Sister Veitch’s electro-therapeutic treatment, administered at her consulting rooms in the George Hotel in Nottingham.27

Despite efforts at prevention and cure, mortality remained high and the R-G’s annual rate of mortality figures for the 96 great towns of England and Wales for the week ending 23 November 1918, placed Nottingham highest on 74, the average being 36.3.28 Undertakers, coffin makers, gravediggers and ministers all struggled to keep pace with the demand for their services. At Beeston it was reported that ‘The constant funeral processions to the cemetery have never had their equal’ while at Hucknall, where an entire year’s burials normally averaged 170, it was reported on 23 November that ‘By Saturday…there will have been 105 interments at the cemetery already this month.29 At Bagthorpe workhouse, so many of the staff and inmates were affected that in a week when 22 deaths had occurred and 28 nurses were incapacitated by influenza, it was reported at the guardian’s meeting that ‘Amongst the victims were the majority of the Board’s workmen, including joiners, the result being that there was no one there to make coffins.’30

In Nottingham, the backlog of corpses awaiting burial, some for as long as a week, reached worrying proportions. However, there was apparently no problem in storing bodies until burial could be arranged, the mortuaries at Hyson Green and Leen Side reported as having ample accommodation.31

The second wave of influenza came to an end in Nottinghamshire in late December 1918, but by February it had returned in the third and final wave. Widespread disruption to public services, industries and businesses followed, schools were closed and entertainments suffered another period of restrictions although the Goose Fair went ahead as planned. Many more deaths occurred, tragically including soldiers who had survived 4 years of trench warfare only to return home and die of influenza within weeks. One such was Lieutenant Reginald Trease D.S.O., M.C. of the RAF. Son of Mr and Mrs George Trease of Waterloo Crescent, Nottingham, he had served with distinction and had been recommended for the V.C. He returned to England following the Armistice but contracted influenza and died from pneumonic complications.32

Wade-Dalton window at St Mary's church, Nottingham.

Other local influenza victims included the Cox family from the village of Kinoulton. William Cox, his wife, sister, son Jack and Jack’s wife all died, leaving Jack’s two small children orphaned.33 Then there was Katherine Wade-Dalton who married in St Mary’s Church, Lace Market, Nottingham, on 23 March 1918 and died of influenza on 30 March 1918 whilst still on her honeymoon; a window in St Mary’s is dedicated to her memory.34 A Nottingham resident whose death appeared in The Times was 48 year old Mr Albert Brough, landlord of the Cremorne Hotel in Nottingham who, at 7 feet 7½ inches tall, required a specially modified hearse to transport him to his funeral.35

In Nottinghamshire, the influenza pandemic finally disappeared in April 1919 and the crisis was over. After the event, the R-G produced a report on the pandemic and its effects on the civilian population. Using mortality statistics he produced charts and graphs to indicate the seriousness of the pandemic across England and Wales. He also used death rates to rank the 335 administrative areas identified, according to their category, these being county boroughs, large towns (over 20,000 population) and remainder of counties (small towns, villages and rural areas), the place with the highest death rate being ranked number 1. Overall, the county borough of Nottingham was placed 6 out of 82, the large towns of Mansfield, Sutton-in-Ashfield and Worksop were placed 90, 18 and 13 respectively out of 161 and Nottinghamshire (remainder of county) was placed 3 out of 61.36

The above figures indicate the severity of the pandemic experience in Nottinghamshire. Why this occurred is possibly linked to the county’s place at the centre of an extensive railways network, connecting urban and rural populations locally and nationally, exposing it to a constant stream of goods and passenger traffic carrying infection into and throughout the area. Furthermore, the high level of industrialization in the county meant that many would have been living and working in conditions conducive to the spread of infection.

Whilst the risks of infection posed by certain occupations during the influenza pandemic, such as public services, factory work and anything involving close contact with others, have been recognised,37 recent research has also revealed the dangers of living and working within enclosed environments during outbreaks of epidemic disease, there being no way to escape the germ laden atmosphere once infection has been introduced. Hospitals, troop ships and mines are noted as amongst the worst places to be at such times.38

During the First World War, power was largely generated by coal and Nottinghamshire’s miners were crucial to coal production for home and military use. As a result, miners who were recently infected or not yet fully recovered from influenza would have continued to work in spite of public health advice, either through patriotic duty or financial necessity, thereby infecting their fellow workers and exposing themselves to the secondary bacterial infections that led to pneumonic complications and almost certain death.

Furthermore, despite the contentions of the R-G and of Dr Thomas Carnwath of the LGB that all sections of society suffered in a similar way regardless of wealth,39 socio-economic status has been raised in recent research as a critical factor, not so much in who caught the flu but rather who died from it and the living conditions of the workers became an election issue at this time.40 Arthur Hayday, labour candidate for West Nottingham, addressing a meeting in the Wollaton Road Schools on 27 November 1918, said:

…the influenza scourge had proved how bad the general housing conditions of the masses of the toilers really were. Mortality had been far heavier amongst the workers than any other section of the community for the simple reason that so many of the poorer people were herded together in wretchedly built and badly ventilated dwellings.41

Hayday’s argument is supported by recent findings, which have revealed a correlation between higher mortality during the pandemic and ‘social disadvantage…overcrowding and poverty.’42

Notes

1. J. S. Oxford et al, ‘World War 1 may have allowed the emergence of “Spanish” influenza’, The Lancet: infectious diseases, 2/2 (2002), pp.111-113. J. S. Oxford et al, ‘A hypothesis: the conjunction of soldiers, gas, pigs, ducks, geese and horses in Northern France during the Great War provided the conditions for the emergence of the “Spanish” influenza pandemic of 1918-1919’, Vaccine, 23/7 (2005), pp. 940-945.

2. P.P. 1920, x, Cmd. 700, Supplement to the Eighty-First Annual Report of the Registrar-General of Births, Deaths, and Marriages in England and Wales: Report on the Mortality from Influenza in England and Wales during the Epidemic of Influenza of 1918-19 (London, 1920), p. 3.

3. Leicester Mercury, 2 July 1918, p. 2.

4. Nottingham Evening Post, 6 July 1918, p. 2.

5. The Times, 3 July 1918, p. 3.

6. Nottingham Evening Post, 28 October 1918, p. 2; Nottingham Local News, 23 November 1918, p. 3.

7. Nottingham Local News, 2 November 1918, pp. 1-2.

8. Nottingham Local News, 23 November 1918, p. 3.

9. Nottingham Evening Post, 22 November 1918, p. 2.

10. Nottingham Evening Post, 22 November 1918, p. 2.

11. Nottingham Daily Express, 11 December 1918, p. 3.

12. F. R. van Hartesveldt, ‘The Doctors and the ‘Flu’: The British Medical Professions’ Response to the Influenza Pandemic of 1918-19’, International Science Review,85/1 (2012), pp. 33.

13. Nottingham Evening Post, 4 November 1918, p. 4.

14. Nottingham Daily Express, 29 November 1918, p. 3.

15. CAB/24/71, ‘Demobilisation of R.A.M.C. Medical Officers’, 4. 12. 1918, London, TNA, p. 88.

16. Nottingham Evening Post, 25 November 1918, p. 2.

17. Nottingham Daily Express, 8 November 1918, p. 1.

18. Nottingham Evening Post, 15 November 1918, p. 2.

19. Nottingham Evening Post, 17 November 1918, p. 2.

20. Nottingham Evening Post, 11 October 1918, p. 2.

21. Nottingham Evening Post, 22 October 1918, p. 2.

22. Nottingham Evening Post, 6 December 1918, p. 4.

23. Nottingham Guardian, 6 November 1918, p. 6; Nottingham Guardian, 23 November 1918, p. 5; Nottingham Local News, 13 July 1918, p. 3.

24. Nottingham Daily Express, 29 November 1919, p. 4; Nottingham Evening Post, 13 November 1918, p. 4; Nottingham Evening Post, 11 December 1918, p. 4.

25. Nottingham Daily Express, 28 October 1918, p. 3; 12 November 1918, p. 2; 5 November 1918, p. 3; 19 November 1918, p. 3; Nottingham Evening Post, 22 January 1919, p. 4; 28 February 1919, p. 4; Nottingham Local News, 8 March 1919, p. 3; Nottingham Journal and Express, 25 February 1919, p. 6.

26. Nottingham Daily Express, 26 October 1918, p. 3; Nottingham Evening Post, 23 October 1918, p. 2.

27. Nottingham Evening Post, 15 March 1919, p. 4.

28. Nottingham Daily Express, 28 November 1918, p. 1.

29. Nottingham Local News, 23 November 1918, p. 3.

30. Nottingham Evening Post, 12 November 1918, p. 2.

31. Nottingham Daily Express, 5 December 1918, p. 1.

32. Nottingham Evening Post, 5 December 1918, p. 2.

33. Nottingham Evening Post, 12 March 1919, p. 3.

34. Nottingham Evening Post, 1 November 1918, p. 2.

35. The Times, 16 January 1919, p. 5.

36. Registrar-General, Report on the Mortality from Influenza in England and Wales during the Epidemic of Influenza of 1918-19, pp. 25-27.

37. K. McCracken and P. Curson in H. Phillips and D. Killingray (eds), The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918-19: New Perspectives (London, 2011),p. 112.

38. J. F. Brundage and G. D. Shanks, ‘Deaths from Bacterial Pneumonia during the 1918-19 Influenza Pandemic’, Emerging Infectious Diseases, 14/8 (2008), pp. 1193-1199; N. Johnson, Britain and the 1918-19 Influenza Pandemic, pp. 108-115.

39 Registrar-General, Report on the Mortality from Influenza in England and Wales during the Epidemic of Influenza of 1918-19, pp. 29-30; T. Carnwath, ‘Lessons of the Influenza Epidemic 1918’, Journal of State Medicine, 27/5 (1919), p.146.

40. H. Phillips, ‘The Recent Wave of “Spanish” Flu Historiography’, Social History of Medicine, (2014), p. 11.

41. Nottingham Daily Express, 28 November 1918, p. 3.

42. D. C. Pearce et al, ‘Understanding mortality in the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic in England and Wales’, Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses, 5/2 (2011), p. 89.