Overview

When Britain became involved in the First World War in August 1914 sending The British Expeditionary Force to France there was a widespread belief that it would be over by Christmas 1914. Young men volunteered to go and fight the ‘Hun’ and do ‘their bit’. As the realisation of a long drawn-out deadlock became reality and the numbers of the volunteers, one million by January 1915, was not enough to keep pace with the mounting casualties the question was how to maintain a regular and sufficient supply of recruits was causing great anxiety to the authorities. It was estimated that at least 30,000 new men were required every week to make up for ‘wastage’. By September, 1915, the voluntary system had apparently almost exhausted itself. There were over two million single men of military age, as well as married men who had failed to answer the call to arms.

By tradition the nation was strongly opposed to conscription in any way shape or form. It was a boast that ours was a Voluntary Army. Voluntarism was associated with freedom whereas, conscription was seen as a state regulation of the lives of its citizens, such as Germany maintained. Among the working classes the feeling against conscription was deep rooted. Examples such as the French Railway strike and the action of the French minister M Briand in 1915 and pro-German agitators threatened the next step from military conscription was industrial conscription. [1] The appointment of Lord Derby in charge of recruiting saw a more robust change in recruiting organisation. The Parliamentary Recruiting Committees was systemised and thoroughly co-ordinated under 46 groups, 23 for single men and 23 for married men; men in their twenties would be called up before those in their thirties and so on and married men would not be asked to serve until the lists of single men were exhausted. Those who wanted to join the colours immediately could do so, the others would wait to be called up. Some trades were exempt from call up in the immediate term. [2]

However, later towards the end of 1915, the government under Herbert Asquith, saw no alternative but to increase the number of men into the armed forces by conscription. Parliament was intensely divided but in view of the state of the war in France and Belgium, they had no alternative but to pass the Military Service Act in March 1916, the first of two Acts imposing conscription on men between the ages of 18 and 41. The first Act was for all single men and the second in May 1916 was extended to married men. The acts applied to England, Scotland and Wales but did not apply to Ireland because of the Easter Rising 1916.

In October 1916 the Irish Nationalist party at Westminster a motion was set out that, '... the system of Government at present maintained in Ireland is inconsistent with the principle for which the Allies are fighting in Europe, and is, or has been, responsible for the recent events and for the present state of feeling in that country.’ The party also passed a resolution opposing conscription, calling for the release of untried prisoners arrested in connection with the rebellion. [3] The UK was not the only country where conscription was unpopular in certain quarters. The Inter-State Trades Union Congress of Australia voiced its ‘uncompromising hostility to conscription’. [4]

Nevertheless, in the first year after conscription over one million men enlisted. However there were those who did not answer the call for a variety of reasons including health, already doing important war work, or moral or religious grounds. Men who appealed on moral or religious grounds were called Conscientious Objectors (Cos). Pacifist members of the No-Conscription Fellowship, set up in 1915, successfully campaigned to secure 'the conscience clause' in the 1916 Conscription Act: the right to claim exemption from military service. A conscientious objector is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of thought, conscience, disability or religion. In general, conscientious objector status is considered only in the context of military conscription and is not applicable to volunteer military forces. [5] Not until 1916 when conscription was introduced did the words conscientious objection enter the language because until then it was all about joining up voluntarily.

Their only way of contesting the ‘call up’ was to go before a local Military Service Tribunal (MST). These had been set up in 1915 under Lord Derby’s scheme, to hear claims for deferring call-up. [6] Their appeal to the MST could be granted on the grounds of moral or religious and the tribunal could grant an exemption, absolute, temporary or exemption from combatant service. The local MST had jurisdiction over its local area. The tribunals were intended to be humane and fair but it was left to local councils to choose the people who actually sat on the panels, and they often selected themselves, “Tribunals were intended to be independent judicial bodies composed of fair minded citizens they were more likely to be made up of elderly local business men former civil servants and policemen clergymen all members of the middle class. With few exceptions they brought their age and class prejudices with them along with those firmly behind the country and its commitment to the war.” [7] Mostly were strongly patriotic and therefore prejudiced against anyone whom they thought was not. Similarly women seemed particularly incensed by the Cos point of view.

The MSTs were further prejudiced by the presence on the panel of a Military Representative, who had a common aim: to get as many men as possible into the army to fill the gaps left by the dead. [8] They were briefed by the local Military Advisory Committee, which emphasised the role of the military in the appeals procedure. [9]

In the period shortly after the introduction of conscription, men who claimed to be conscientious objectors found it difficult and were often ridiculed, called cowards and some were physically abused. According to contemporary commentators, the MSTs helped to augment the extraordinary number of young men who converted to new religious fellowships, societies and Quakerism in order to avoid being sent to the Front. [10] They were also vilified by those men already serving in France. A letter sent home from the Front clearly illustrates the thoughts of one officer on conscientious objectors.

“They also serve who stand and wait. That doesn’t apply to those curs of objectors: when we go the papers with the photos of that Trafalgar Square racket, to say that we were disgusted and enraged was putting it mildly. They will go through it when we return; the sinners. I was glad to see that two of them got 2 year imprisonment with hard labour for what amounted to mutiny when called up. Serve them jolly well right and they are getting off lightly to what they deserve, it is our bete noir are they worth fighting for?” [11]

In another incident at court in Nottingham, supporters of a conscientious objector, had their exit blocked by the police and each man of military age was challenged to show why he was not serving his country. Of the six, four were able to immediately show they were exempt and the other two had to await their papers being produced by friends despatched to find them. [12]

They were even singled out by protesters complaining about food plunderers at a demonstration in Nottingham Market Square. J A. Seddon, ex-president of the TUC condemned the attitude of the Conscientious Objectors and declared that they were fit company for neither man not beast and they were as bad as the food profiteer. [13]

Having introduced conscription, Parliament, both upper and lower houses, was continually reviewing how the system was applied to conscientious objectors. The fiery Colonel Norton-Griffiths, MP for Wednesbury (1910-1917) said it was imperative that there should be no interference with the existing military arrangements; Harold Tennant, under Secretary State for War, stated that there must be machinery to deal with Cos but that must not create an easy path for those with recently-developed consciences but the government would not condone any persecution of objectors. [14] The House of Lords discussed the question of conscientious objectors and several issues were raised. While it was hoped that liberal measures of protection should be given to sincere objectors, no such protection should be given to those merely claiming conscientious objections to shelter themselves. A young man, Leonard Fox, was charged with failing to report himself for military service on 30th August 1916 claiming he was a conscientious objector, but the clerk said that was no defence and he was fined 40s and handed over to the military authorities. [15] Earl Russell suggested that the authorities should try and avoid friction with objectors and they ought not to be dealt with harshly. It was agreed that the President of the Local Government Board had done his best to ensure proper treatment was given to objectors. [16]

The Cos can be divided into three categories, according to their strength of belief. The ‘absolutists’ who were not only opposed to conscription but to the war and any alternative service supported the war effort. They could be granted complete or unconditional exemption. The ‘alternatives’ were prepared to take alternative civilian work not under any military control and could be exempted from military service provided they actually carried this work out. Lastly the ‘non-combatants’ who were prepared to join up but not to be trained to use weapons or anything to do with weapons. They could be put on a military register on this basis. Unfortunately from the very outset there was an issue which involved Cos and MSTs and what the definition of what constituted acceptable conscientious grounds and this caused wide variations in interpretations. The only real agreement was that acceptable conscientious objectors were members of the Society of Friends. [17]

Cyril Pearce’s ground breaking work on conscientious objectors concludes that, there is no accurate assessment of the numbers of Cos in the UK as a whole. The data is based on fragmentary, flawed or non-existent material, biased and open to conflicting definitions. [18] Many of the tribunal’s paperwork has been either destroyed or lost, with some notable exceptions such as Huddersfield, Northampton and south Warwickshire. Nottinghamshire, unfortunately is one area where there is no trace of the MST. However, referencing the local paper, The Nottingham Evening Post, reveals the names of men who claimed conscientious grounds for not joining up and some indication of what happened to them after their appearance before the tribunal. Further investigation concludes that there were at least 253 men registered as Cos in Nottingham after 1916. They came from all walks of life and were placed in a number of different occupations throughout the war.

The Church of England supported the war so it not surprising that many of the 253 men listed as Cos in Nottinghamshire were of a strong religious background, including Quakers, Christadelphians, Congregationalists, Jewish, Seventh-Day Adventists as well as some who were Church of England. Others were listed as Atheists, believers in God, members of the Independent Labour Party or just religious. Each one has a story and a reason for claiming to be a Conscientious Objector. In this article I have selected some of the 20 Nottingham men who became members of the Friend’s Ambulance Unit (FAU), which was a civilian volunteer ambulance service set up by a group of Quakers during World War I. Its members from 1914-1919, were both Quaker and non-Quaker, but mainly Quakers or who attended Quaker meetings. They came from diverse backgrounds, such as Felley Priory, home of the Chaworth-Musters; an academic from Oxford University; three brothers who lived on Alfreton Road and a railway clerk from Nottingham.

Harold Adair Armitage, was 30 years of age in December 1915 when he joined the FAU. His FAU service card states he was single living with his father at 5 Derby Terrace, The Park, Nottingham and was a member of the Society of Friends. He was given an absolute exemption on the grounds of his conscientious objection. He was a draughtsman by trade and was a useful member of the service because he had a St Johns first aid certificate, he spoke a little French and was an electrical and mechanical engineer. He began his service at Kursaal, Dunkirk [19] on 7 January 1916 as a mechanic. He served also at Parc St Georges, Kortrijk, Belgium and Steenvoorde, northern France as a mechanic until 1/2/1919 when he left the unit.

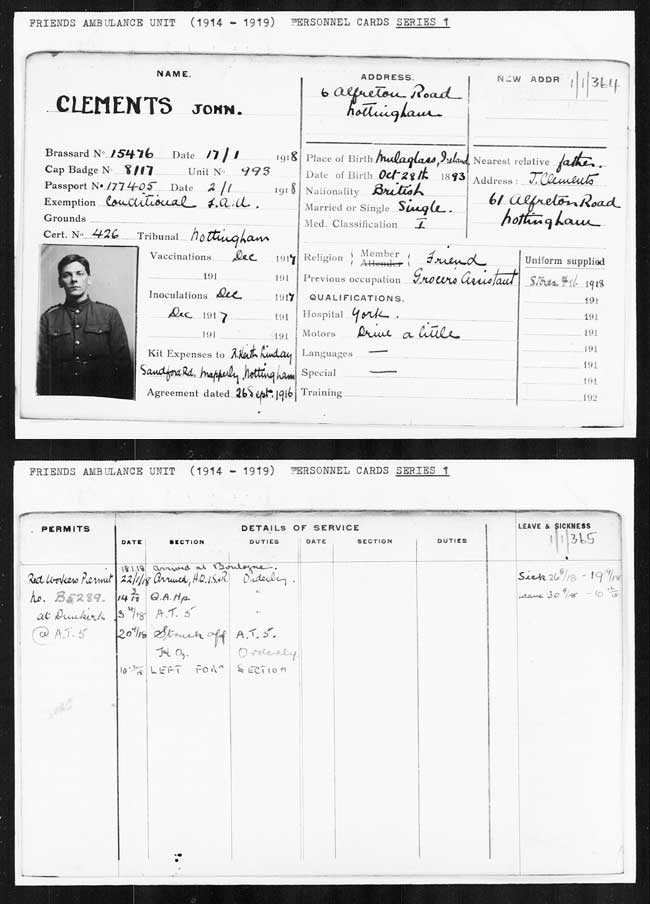

Three brothers who were all born in Mullaghglass, Ireland and were members of a large family of nine children all served in the FAU. John Clements (photo) of 61 Alfreton Road, Nottingham, a single man and a grocer’s assistant appeared before appeared before the Military Service tribunal in Nottingham on 21 March 1916 and claimed absolute exemption but was only granted exemption from combatant service; he appealed against this on 1 May 1916 but the ECS was upheld and he was recommended to join the FAU as of June 1916. He worked on a farm in Wareham until January 1918 when he was sent to Boulogne and joined Ambulance Train 5 and transferred to Uffculme Hospital, Birmingham until his discharge at the end of 1918. He knew Robert Keith Linday, who provided his kit. John’s elder brother, William James Fulton of 15 Alfreton Road was a motor driver and a member of the Quakers. He was granted exemption from combatant service conditional on he joined FAU as work of national importance within 21 days. He served from 17 May 1916 mainly in and around Norfolk until his demobilisation on 14 December 1918. The younger brother, Thomas Clarke Clements, born 6 February 1897, was given an exception from combatant service on 13 April 1916 and referred to the FAU 22 May 1916 as work of national importance. His occupation was that of a groom and general farm worker and he was posted to Norfolk for the duration of the war and demobilised on 18 November 1918. [20]

Frederick Berwyn Goosey, a 32 year old clerk to the motor trade, of 222 Wilford Road, Nottingham, was given a conditional exemption, certificate number 428, in June 1916 to join the FAU. From August 1916 until his discharge in December 1918 he worked on farms near Oakham and Stamford.

John Hughes. © Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain

John David Ivor Hughes was born in Nottingham in 1885, a single man. He attended Nottingham High School and in 1904 went to Aberystwyth, not formally as an undergraduate to read for a degree, but to attend lectures in law with a view to qualifying as a barrister. He soon moved to London and was called to the bar at Middle Temple in 1910; in 1911 he went up to Balliol, a somewhat mature student, and distinguished himself by taking a first in jurisprudence in 1914. He then read for a BCL, which he took in 1915, and was awarded the Vinerian Scholarship. During the First World War he was given an exemption from combatant services, certificate number 252, by the York City Tribunal on 23 March 1916 provided he joined the FAU, although he is not specified as a member of the Quaker movement. He had some qualifications in First Aid. He joined the FAU in July 1915 and served in York, Jordans (the training centre) and the London Office [21] before going to Boulogne, France on 21 September 1918. He was demobbed in February 1919 and later that year he was appointed professor of law at Leeds, where he remained until his retirement in 1951. He died in 1969. [22]

Joseph Bliss. © Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain

Joseph George Bliss, a 17 year old railway clerk of Albert Road, Lenton, Nottingham was a Quaker who attended the Nottingham and Mansfield Houses for monthly meetings. He was a single man. At his Military Service Tribunal he was exempted from combatant service on the condition he worked with the FAU. He had first aid training through the British Red Cross Society and he went to Dunkirk working as an orderly on Ambulance Train 16 [23] in November 1917 and was discharged on 25 February 1919.

Two more brothers were also members of the FAU. Artin Der Stepanian and his brother, Walter, both living in the Meadows, Nottingham. Although there is information on Artin, there is less on Walter. Artin was a 16 year old audit clerk whose father was a Turkish Armenian and his mother English. He was granted an exemption from combatant service on condition of joining the FAU in September 1918 where he was sent to Boulogne where he served as an orderly on Ambulance Train 5 until his discharge in February 1919.

Alfred John Dodd of Felley Priory, Jacksdale, Nottinghamshire was a pharmacist. He was 34 years old and a single man. He was not a Quaker but was granted a War Office certificate 280 in March 1916 to join the FAU. He was fluent speaking in French and had a St John’s first aid certificate. He served as a pharmacist throughout his service at Ypres, Hazenbruck [24] and Abbeville [25] . He left the service in February 1919.

Eric Hollingworth England and his elder brother Noel, both of 4 Park Street, Nottingham and single men, were granted conscientious objector status; Eric was granted an exemption from combatant service if he joined the FAU, whereas Noel was already serving in the FAU and claimed an absolute exemption but was only granted an exemption from combatant services. Eric was an analytical chemist whereas Noel was a warehouseman. Their parents were members of the Quaker movement and Eric was a regular attender. There is no mention of Noel attending any meetings. Noel was granted a War Office certificate no 329 in November 1916; he had some knowledge of the French language and treating wounds and held a St John’s first aid certificate. He served in Dunkirk as an orderly from March 1916 until January 1919. His brother Eric could speak French and he too had a St John’s certificate. He served at Boulogne as an orderly from April 1918 until February 1919.

A further set of brothers, were James Allan, aged 28 years and Robert Keith Linday, 27 years. James was single and an engineering foreman and member of the Society of Friends. He received a war office exemption and was an orderly from November 1915 until his discharge in January 1919. From June 1917 until his discharge he was a steamer orderly. His brother, Robert, was a married man and was given an exemption from combatant services to join FAU. He was posted to the Queen Alexandra Hospital, Dunkirk, in October 1918 where he served as an engineer until his release in January 1919.

William Pickard, a 24 year old wholesale grocer from Mansfield. He had already been accepted for training with the FAU but appealed on grounds of CO, and was given an absolute exemption providing he worked with the FAU. He could drive and was a member of the Society of Friends. He had a variety of occupations during the war years; he was an orderly in 1916 and then joined a hospital ship [26] and then worked in Queen Alexandra Hospital. In 1918 he twice worked in construction at Porte Synthe but then went back to working in the hospital until his discharge in January 1919.

Harold King Price, a 23 year old dental student joined the FAU in March 1916, having had his claim to the Basford Rural MST for exemption from combatant services and non-combatant corps refused. His father is recorded as a farmer of East Markham, Newark in 1911. Harold was an attender of the Friends and was accepted into the membership shortly after joining the FAU. His records are sketchy and give little detail what he did during the period of time he was in the FAU; he was classed as an orderly and served at King George Hospital and Haxby Road Hospital, York [27] until 1918.

Walter Reginald Houseley, a 21 year old junior clerk to the Divisional Superintendents Office Great Northern Railway, was given an exemption from combatant services in March 1916 and recommended by the tribunal for work with the FAU. In August 1916 he was posted to the King George Hospital and went to Dunkirk on 13 February 1917. He served as an orderly at Queen Alexandra Hospital, Dunkirk until October 1918. He was demobilised in January 1919.

The men listed above are but a few of the 253 Conscientious Objectors listed in Nottinghamshire. The majority claimed to refuse to take the colours because of religious motives, but there are some who were Trade Unionists or members of the Independent Labour Party. Unfortunately the MST records which would give more information on area such as the arguments given by the CO and reasons given for the decisions made, are no longer available for Nottingham so it necessary to look elsewhere for details on these men who only in the last few decades have become more accepted into history. Newspapers give some information but tend to be brief. Enquiries with the Society of Friends, Nottingham have so far revealed nothing. All of the men, except one, who joined the FAU was single. Among these men were several sets of brothers and it is interesting that of the Linday brothers the single one, James Alan was given an absolute exemption whereas the married brother was only excused from combatant services. All of the above men were members of the Society of Friends and claimed exemption from combatant services.

Archival

Nottinghamshire Archives

Military Tribunal Records

DC/NK/21/1 - Newark

DC/BS/1/9/1 - Beeston

DC/BS/1/10/1 - Beeston

DC/SW/1/2/5/1 - Southwell

DC/K/1/7/1 - Kirkby in Ashfield

DC/C/1/3/10/1 - Carlton

The Military Tribunal Records for Beeston are not very helpful but the others have more information contained in them.

Correspondence

DD2402/1/26 - letter from Lieutenant Thomas Moore Ward (15 April 1916 )

The Library of the Religious Society of Friends

(Friends House, 173 Euston Road, London NW1 2BJ : fau.quaker.org.uk)

Details of men who volunteered for the FAU.

Index card for John Clements. © Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain

Printed

H W Wilson and J A Hammerton. The Great War. (The Standard History of the All-Europe Conflict )

Cyril Pearce, Comrades on Conscience : The story of an English community’s opposition to the Great War, 2001, Bath Press. (The most comprehensive book on Conscientious Objectors) He has a comprehensive register of all known men who volunteered for the FAU.

John Bucknell, 'The conscientious objectors of Northampton during the First World War', Local Historian, 46/3, 2016.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conscientious_objector 24 October 2016

'Conscientious Objection' http://www.ppu.org.uk/men/context/context_con_objection.html. 30 August 2016

References

[1] Eds. H W Wilson and J A Hammerton. The Great War. The Standard History of the All-Europe Conflict, Volume 7, Chapter CXXIII, pp 35-57

[2] The Great War. Volume 5, Chapter XCVIII, pp 397-421

[3] Nottingham Evening Post, 10 October 1916

[4] Nottingham Evening Post, 12 May 1916

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conscientious_objector 24 October 2016

[6] Cyril Pearce, Comrades on Conscience. The story of an English community’s opposition to the Great War. P 161, 2001, Bath Press, p.159

[7] Pearce, Comrades on Conscience, p.161

[8] Conscientious Objection. www.ppu.org.uk^cos^st_co_wwone. 30 August 2016

[9] Pearce, Comrades, p 161

[10] The Great War. Volume 7, Chapter CXXIII, p.40

[11] Nottinghamshire Archives, DD2402/1/26, 15 April 1916 letter from Lieutenant Thomas Moore Ward

[12] Nottingham Evening Post, 18 September 1916.

[13] Nottingham Evening Post, 11 September 1916

[14] Nottingham Evening Post, 31 May 1916

[15] Nottingham Evening Post, 14 September 1916.

[16] Nottingham Evening Post, 5 May 1916

[17] C Pearce Comrades, p 160

[18] Ibid p 170

[19] The First Anglo-Belgian Ambulance Unit, later Friends Ambulance Unit, set out for Dunkirk on 31 October 1914. Headquarters were established at Hotel du Kursaal, Malo-les-Bains on 2 November.

[20] These may have been placements doing agricultural work, if it was after mid-1916, as this work became common for COs who were not fit for ambulance work. The General Service Section was part of the Home Service Section. It was established in 1916 and was a direct result of the Military Service Acts of that year. The section organised work for conscientious objectors who for financial or other reasons could not join the FAU. Mostly, the men undertook agricultural work organised by the Agricultural Sub-Committee, but they also worked in education, welfare, building construction, surgical appliance making, forestry, flour-mills or food factories.

[21] Jordans was the location of the FAU training camp for all men before they went off to work; London office is the London office of the FAU, based at Weymouth Street, which organised all the logistics, applications for membership etc.

[22] There are some papers which Hughes kept at Aberystwyth and Oxford which are currently held in the Manuscript Department, Leeds. They include notes from lectures given by Professor W J Brown at Aberystwyth and by Professor Henry Goudy and Professor Paul Vinogradoff at Oxford. The greater part of the material is on aspects of Roman law.

[23] FAU Ambulance Trains provided relief behind the British front.

[24] Musée Hospital, Hazebrouck (1915-1917); the Casualty Clearing station

[25] No.3 British Red Cross Hospital, Abbeville

[26] There were 2 Hospital Ships, The Western Australia and The Glenart Castle

[27] Haxby Road Hospital, York (opened 1915); King George Hospital, London (opened 1916); Uffculme Hospital, Birmingham (used as a hospital from 1916)