Introduction

Nottinghamshire Deaf Society (NDS) is a registered charity, formed in 1890 to support the Deaf Community in Nottinghamshire. It is based at 22 Forest Road West and provides welfare, social and campaigning activities, with classes in lip reading and British Sign Language (BSL). NDS has changed its name many times over the last 130 years and the term ‘society’ has been used as a catch all description. Many of the community elders have BSL as their first language and over the last fifty years have fought for self-determination, in one of the few dedicated Deaf Centres still remaining in England.

Early Deaf History

There is evidence of deaf people using sign language since at least the seventh century; in England the earliest document noting sign language is 1575 within the Registry Records at St. Martin’s Church, Leicester in a marriage document between Thomas Tilsye and Ursula Russel. John Bulwer’s Chironomia or Art of Manuall Rhetorique (1644) demonstrated an established format for the use of finger spelling. By the nineteenth century formal societies founded for or by deaf people are recorded.

The UK’s first formal Deaf Society was established in Glasgow 1822 with Nottingham establishing the Institute for the Deaf (NID) in 1868. NID was established by a hearing man, Alderman Cropper (1815-1894) who wanted deaf people to read the bible and participate in church services, as reported in the Nottinghamshire Guardian Nottinghamshire Guardian in 1874.

‘In this locality there was a gentleman who had had the largeness of heart and the sympathy to gather round him, Sunday after Sunday, so many of our fellow creatures to instruct them in the truths of the gospel, to convey to them the plan of salvation, to endeavour to give all their hearts and feelings an impression of love and joy and comfort.’

Nottingham and Nottinghamshire Adult Deaf Society’s Missionary’s Log Book, 1894-1898 (credit NDS)

Religion was a common motivator at this time, early Society log books record ‘Missioner’ visits to monitor church attendance rather than providing practical support. Image 1

In 1896 the Society appointed a deaf man, Hiram Blount, as superintendent. His duties included ‘conducting religious services in sign-language, acting as an interpreter during lectures, being ready to visit urgent cases of sickness etc. and devote himself exclusively in his spare time to the work of the Society.’ He moved on to the Plymouth Mission for the Deaf in 1899 and another deaf man John William Greaves, took over to conduct Sunday services with the school teacher, Mr Green, as secretary.

So now the Society was led by deaf people, but its tone remained religious, deeply paternalistic, and Oral (deaf people should ‘fit’ with society through lip reading and speaking rather than using sign language) “They pass through life silent, terrible monuments of the mysterious will of God – no thought of heaven or glory. Fatherless, redeemerless, spiritless, hopeless – unable to interpret their woes – and in awful ignorance” (1892 Annual Report). However, sign language was used to inform members “With a celerity which surprised many of those present the speeches at the Annual Meeting of the Nottingham and Notts Adult Deaf and Dumb Society were interpreted by the secretary to the deaf mutes by means of the manual alphabet and signs. Mr Green (the sign-language interpreter) was able to keep pace with the speakers and the applause with which the deaf people greeted many of the observations told how clearly they understood everything that was going on.” (Nottingham Daily Guardian, 1905)

Around this time, we see the emergence of national magazines for the deaf including the British Deaf and Dumb Times.

The Twentieth Century

Moving into the 20th century we see hearing people taking control over the Society again, very much on a charitable model. Various members of the ‘Nottingham elite’ became involved, including James Forman of Thomas Forman & Sons and A R Tweedie, an Ear, Nose and Throat Surgeon at Nottingham General Hospital. The demographic of the local deaf community changed post WW1 with 242 ex-servicemen returning to Nottingham with hearing loss. These men needed to learn to lip read and receive support to gain work. Taking a snap shot from the Annual Report in 1926 we learn that the Society now had 812 deaf members and up to 70 people attended church service.

Nottinghamshire Deaf Society centre today (credit NDS)

Nottinghamshire Deaf Society centre today (credit NDS)Tweedie recognised that the increased demand for services meant the Society needed a permanent home, and after raising £7,000 from public subscription he steered the acquisition of the old Congregational Institute on Forest Road. The building offered a large hall, office, committee room, billiards room, and a separate room for women. The grand opening for the new building took place in 1931 with many VIPs including the Duke of Portland.

In the 1930s the Society had a clear aim ‘To encourage them in habits in industry and sobriety and to live moral and religious lives.’ Activities included: sport for men and women, a library, a chapel, an ex-servicemen’s group, lip-reading classes, social events, children’s activities, interpreters, employment advice and support for those in ‘necessitous circumstances. The Society promoted employment opportunities with local employers, and established a boot and shoe repair workshop to train and employ deaf men. The workshop continued right through to 1966.

The Society’s efforts were so successful that the 1934 Annual Report stated there were only 2 deaf people unemployed in the county!

A new Superintendent Mr Fox was appointed who “visits the sick, has to be present at all times when the building is open, interviews possible employers, interprets, deals with domestic disputes, arranges events and outings. Mrs Fox always at hand when a woman’s help is needed.”

During World War 2 the Society’s building was passed over to the local air wardens, and the deaf school moved to Normanton Hall in Southwell.

After the war the Society evolved further with the introduction of the National Assistance Act (1948) when local authorities took over responsibility for services to disabled people. This allowed the Society to increase services including new branches in Worksop and Newark, and support for deaf patients at Rampton.

When Mr Tweedie died in 1936, his widow took over as chairman, followed later by their daughter. The Society is now “the embodiment of an attempt by socially-conscious, non-handicapped people to convey to deaf people their sensitive awareness of the problems encountered by deaf people to their daily lives”. Whilst authorities continued to push Oralism the Society provided opportunities for deaf people to learn and communicate via sign language. Videos from the 1950s and 60s show this was mainly finger spelling, rather than the more rounded sign language of today. Evelyn Steele recalled “When I left school at 16, I came to the Deaf Club here. I remember at that time it was full of old people using fingerspelling to communicate with each other. I was from India and I struggled to understand what they were saying.”

Rise of Deaf activism and the fight for BSL

The 1970’s saw a number of changes in the attitude and public role of deaf people. Two deaf people were appointed to the Society’s Executive Committee, but it was 1980 before they were allowed an interpreter at committee meetings.

In 1971 the UK noted the first documented use of the term British Sign language (BSL), prior to that, terms such as manual signing, or finger spelling were commonly used, and in 1975 the first BSL classes were started for hearing people to learn to sign.

By 1978 the Society had activities for every day: social, sports, welfare, educational and of course church on Sundays. The Society organised holidays (including for deaf children) around the UK and abroad. These have been caught on videos and photos held at the Society’s Archive.

British Deaf Association manifesto, 1982

British Deaf Association manifesto, 1982In 1979 impatient for change The National Union for the Deaf was formed – this is when a capital D in the spelling of Deaf started to be used – reinforcing a new political identity. In 1982 the British Deaf Association launched their eight-point manifesto, “We ask to be heard.”

In 1985 Deaf people walked out of the International Congress on the Education of the Deaf and organised an ‘Alternative Conference’ at Manchester’s Deaf Centre. Deaf historians regard this as the ‘true birth’ of the campaign for the use and the recognition of British Sign Language. One of its key successes was the commission of the BBC ‘See Hear’ TV series. Deaf tutors (rather than hearing people) started to teach BSL. Access to these courses was subsidised by Local Authorities to enable more people to learn the language (the author attended classes in London around this time), interpreting became a profession, rather than an add-on to a social worker’s job. In Nottingham we started to see interpreters at local theatres.

In 2003 another radical group was established, as local activist Anne Darby explains “The idea came from the British Deaf Association. We were campaigning for BSL recognition by government and so we set up the Federation of Deaf People to fight for BSL recognition nationally … We could take a more political stance as the FDP. After the BSL charter was set up, many organisations in Nottingham were happy to sign up. That’s why Nottingham as always is in the forefront as all our organisations are willing to work together, share resources, share ideas and set up Deaf events.” In 2003 BSL was finally recognised as an official language by the UK government, and in 2010 the 21st International Congress on the Education of the Deaf, held in Vancouver, finally apologised for enforcing ‘Oralism’ at the Milan Conference of 1880.

Today the Deaf Community continues to be vocal - they organised a sit-in against funding cuts on the tram lines at the Market Square in 2010. The use of cochlear implants, integrated schooling, and the use of technology have left many individuals struggling with their Deaf identity. Many younger Deaf people do not learn BSL, many Deaf Centres have closed in the last 20 years, and those that remain tend to be used by older people, but BSL classes are popular as a growing number of people are seeing interpreting as a good career choice, to support community elders.

Education for the Deaf

Holly Mount House, Nottingham first deaf school (credit M Cooper)

Holly Mount House, Nottingham first deaf school (credit M Cooper)In the UK the first formal Deaf School opened in Bermondsey in 1792, but it was the Education Acts from 1870 onwards that provided for education for all children. At this time, it was estimated that only 3,000 of the 5,000 deaf children in England were in education. In Nottingham the School Board provided some education in various venues and in 1883 set up a new Deaf School at Holly Mount House in Clarendon Street, the school stayed there 50 years.

The founder and headmaster of the school was Mr C H Green, a hearing man proficient in signing. He was an ‘Oralist’ and raised funds by getting the children to show how they were taught to speak, as can be seen in this newspaper article from 1889.

‘An interesting entertainment in connection with the deaf and dumb school … was given in the Sunday schoolroom of the Wesleyan chapel Mansfield Road, Nottingham last evening. A number of pupils in various stages of progress in speaking were called on to the platform during the evening, and the system of teaching was thus practically illustrated.’

Nationally and internationally during this time some schools and societies offered deaf children and adults opportunities to develop their signing skills, however a major challenge to this practice took place at the International Deaf Education Conference in Milan in 1880 when it was declared that the ‘Oral Method’ of education should be used in education and that sign language should be suppressed.

In 1930 the Nottingham School for the Deaf moved to the new Deaf Centre on Forest Road, providing education for 60 to 70 children, as young as 2 years old. Interviews with community elders show a great affection for this school, although sign language was very much a playtime activity. Margaret Mee recalled ‘I didn’t sign at school because it wasn’t allowed. If you got caught signing, you’d get a slap on the wrist. The classroom was for speaking, listening and learning, not signing.’

Gloria Pullen added ‘it’s interesting that in school we would sign in secret under the desk. If we were caught, we would be punished. Also, I would have more access to information because I attended the deaf club with my parents. So, on Monday I would come back to school and tell all the children the news.’

In 1960 the school moved to the purpose-built Ewing School on Mansfield Road under the headship of Mr French.

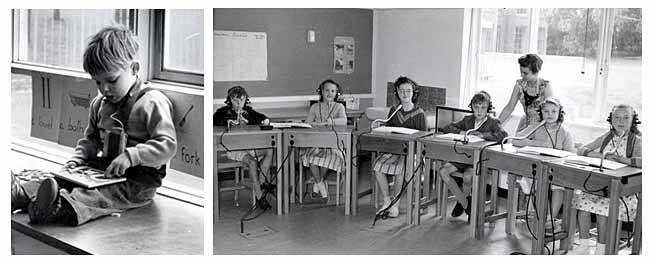

Left: Ewing School 1960s (note large portable amplifier that children were expected to carry with them)

Right: Ewing School 1960s, showing desk amplifiers as described in Stephen Mather’s interview (credit NDS)

Many of the people interviewed during the project discuss enforced oralism and large machines attached to little children. Stephen Mather’s interview explained: 'At my desk, I had headphones plugged in, … On the left-hand side, the volume would be set to number five, on the right it would be set at zero as I’m profoundly deaf in my right ear. … so, I turned it down to zero. The teacher would walk round and she saw it was set at zero, she asked me why and I said I was deaf in my right ear. They said I had to turn the volume up to 10. I turned it right up and it was just an awful noise…. The next day, back at school I had it back down at zero, when the teacher walked past, I turned it right up to 10, and as soon as they went, I turned it back down to zero.’

For younger people these modern schools were an improvement. Garfield Hodelin said ‘It was different here in England, it was better. We had interpreters, people could sign and communication was good. Everyone could sign well. In school in Jamaica, I didn’t understand anything, it was difficult to communicate’.

In 1978 The Warnock Report was published, advocating the integration of deaf and disabled children into mainstream education. This eventually led to the closure of many specialist and residential schools, including Ewing in 1994. This move was not always welcome by Deaf people - Ben Thompson recollected “I was born in Nottingham but eventually we moved to Derby because at that time, the council refused to fund a specialist school placement, so I ended up being educated at the Deaf School in Derby.” Derby Deaf School remains the only local specialist school in the Midlands.

This article is based on research undertaken as part of the Heritage Lottery Funded ‘Hearing Deaf Voices’ project (2016). Details of the project, and a lovely 15-minute film can be found at https://www.nottsdeaf.org.uk/hearing-deaf-voices.

Resources and further reading

Nottinghamshire Archives have various documents relating to NDS – see Reference No DD/2016, Accession No 5183, Title NOTTINGHAM AND NOTTINGHAMSHIRE DEAF SOCIETY, Date 1927-1995

Nottinghamshire Deaf Society have a private archive of photos, reports and memorabilia – access via NDS

Video, time line and more images: see https://www.nottsdeaf.org.uk/hearing-deaf-voices/

Understanding Deaf Culture: In Search of Deafhood, Paddy Ladd, Multilingual Matters (2003), for a full dialogue on the politics of Deafhood

https://bda.org.uk/project/heritage-project/ - national heritage project

https://www.historypin.org/en/share-the-deaf-visual-archive - great videos and resources collected by BDA over the last 5 years.