Despite Booth’s early life in Nottingham and the beginnings of his life of preaching in the borough, after his move to London in 1849 his links with his home town were severed and many visitors to the museum which was once his home do not know the great man hailed from Nottingham.

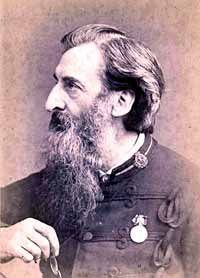

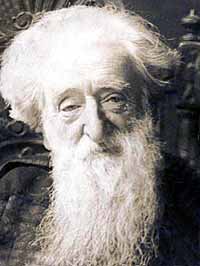

It can be said that William Booth’s Salvation Army was a product of his early life in Nottingham. He was born on 10 April 1829 at 12 Notintone Place, Sneinton, a village just outside of the town boundary, but today a part of Greater Nottingham. His parents, Samuel and Mary Booth, came to the borough around 1824. Mary was Samuel’s second wife and gave birth to three daughters, Ann, Emma and Mary as well William who was the third child. There had also been an elder son but he had died at the age of two years. He was baptised at St Stephen’s parish church, which was described as an Anglo-Catholic church with papist inclinations and eighty years later, William wrote that he left the Church of England because in his childhood he had found the services unfriendly.

The Booths were neither well off nor poor and in fact during William’s early life, his father made several business ventures, some prospered and others failed and the family fortunes fluctuated. During his early life, the Booths had left Sneinton but had returned when life was more favourable.

In October 1831 the family moved to Bleasby, a village, 12 miles north of Nottingham. They lived in what is now The Old Farmhouse. Samuel had taken up farming and was renting ten acres of land to breed rare sheep and cattle, or as William later described it ‘fancy farming’. William ‘learned his letters’ at the village school, which practised the strict language of the Anglican Church. The farming experiment obviously did not work as the family moved back to Sneinton in 1835, to a house on the corner of Bond Street, a short distance from his birthplace. Samuel was now classed as a jobbing-builder and was able to send his son to Biddulph’s school, which had been founded by local Methodists.

William favoured his mother and over his father and claimed in later life that, "My father was a Grab, a Get. He had been born into poverty. He determined to grow rich; and he did. He grew very rich, because he lived without God and simply worked for money; and when he lost it all, his heart broke with it, and he died miserably." However Samuel made a death-bed repentance. William would have liked to have gone to America to preach but would not because he did not want to leave his elderly mother who previously had to leave her house in Sneinton for a small shop in one of the poor quarters of Nottingham where she earnt a meagre income selling toys, needles, cotton and the like.

Nottingham borough at the beginning of the nineteenth century was of a modest size with a population of around 28,000. It had attracted a migrants, especially to the framework knitting industry, but this had put pressure on the limited space for manufacturing and housing. The town was confined to a small area because of the failure to enclose the surrounding land. The Nottingham Enclosure Act 1845 failed to deliver its honourable intentions for another twenty years and so the old town became a place of slums, tightly crammed houses, cheek by jowl with small noxious industrial works with no open spaces. The population by 1850 had almost doubled and was about 58000. The young William Booth would have been exposed to these slums and the poverty embedded in them and would later in his life when he was living in London and had begun preaching that he said When I saw those masses of poor people, so many of them evidently without God or hope in the world, and found that they so readily and eagerly listened to me

Whilst his father was alive William accompanied him to St Stephen’s Church and attended Sunday school. However, he also occasionally attended the Broad Street Wesley Chapel through his friendship with Samson Biddulph, the founder of the Biddulph School he attended.

In 1842 at the age of thirteen years his life was changed forever, as the various financial dealings of his father came to an abrupt end leaving him bankrupt. William was now taken out of school and apprenticed to a Francis Eames, a pawnbroker of Goosegate, Nottingham. Here he would have seen the dark side of poverty with people pawning and re-claiming goods day in day out. Francis Eames and other pawnbrokers had a close connection with the Non-Conformist Church.

Two years into his apprenticeship Booth abandoned the Church of England and was converted to Methodism in 1844. He then read extensively and trained himself in writing and in speech, becoming a Methodist lay preacher. Booth was encouraged to be an evangelist primarily through his friend, Will Sansom, the son of a well-to-do lace maker. Sansom and Booth both began in the 1840s to preach to the poor and the sinners of Nottingham who were the only people who the pair had of any real hope of success. Booth would probably have remained as Sansom's partner in his new Mission ministry, as Sansom titled it, had Sansom not died of tuberculosis, in 1849.

During his time as a pawnbroker’s apprentice he became increasingly aware that the Lord was calling him to do good work. He was very much interested in itinerant evangelism, in other words, moving from pulpit to pulpit stirring spiritual awakening. When he had successfully completed his apprenticeship he was unable to find a job in either pawn broking or anything else and this was partly because his main desire in life was to preach. In 1849 William moved to London and went to stay with his sister Ann and her husband Francis Brown, but as they were both drinkers he did not stay with them long. He briefly returned to pawn broking in Kennington but also joined a chapel in Clapham. Through this church he was introduced to his future wife, Catherine Mumford. He tried to continue lay preaching but the small amount of work available frustrated him and he returned to his love of open-air evangelising in the streets and on Kennington Common. On 16 July 1855 William and Catherine married and became a formidable and lifelong partnership. They had a brief honeymoon at Ryde on the Isle of Wight. They had eight children from their marriage.

In September 1855 they visited Sheffield together as a couple and were joined there by Booth’s mother who travelled from Nottingham. Despite William and Catherine’s upbeat view of their ‘revivalist’ meetings, the local newspaper, the Sheffield and Rotherham Independent did not mention William once, and in fact he was forbidden to preach in the south of the town because it was felt he was getting above himself. It is at this time that there was a deterioration in the relationship between Booth and the other Methodist ministers over his alleged conversions

He became an evangelist with the Methodist New Connexion and was appointed to circuits in Halifax and Gateshead but found this structure restrictive and felt he was unable to follow his true vocation for itinerant evangelism, and he resigned in 1861. It was also around this time that the Reverend PJ Wright, Superintendent Minister of the Nottingham Circuit and a critic of Booth and his preaching was elected to the Conference Standing Committee and later insisted that the constitution did not allow the creation of a missionary institution for the conversion of heathen England. So Booth decided to become an independent evangelist, travelling around Cornwall and then onto Cardiff and then to Walsall. His doctrine remained much the same, he preached that eternal punishment was the fate of those who do not believe the Gospel of Jesus Christ and the necessity of repentance from sin, and the promise of holiness. He taught that this belief would manifest itself in a life of love for God and mankind. Booth and his wife found their life hard work and were very often ‘within the sight of poverty’. He left the north and travelled to London where they began their life’s work.

By 1865 William and Catherine Booth were preaching to the poor and destitute of London's East End, and brought the good news of Jesus Christ and his love for all. Booth soon realised he had found his destiny, and later in 1865 he and his wife Catherine opened 'The Christian Revival Society' in the East End of London, where they held meetings every evening and on Sundays, to share the repentance that salvation can bring through accepting Jesus Christ as Lord and Saviour to the poorest and most needy, including alcoholics, criminals and prostitutes. The Christian Revival Society was later renamed The Christian Mission and from the autumn of 1878 it became known as the Salvation Army. As well as offering salvation through God they also helped by setting up soup kitchens and offered social help to the poor and needy.

On 13 January 1875, Booth’s mother died but there is no mention of William returning to Nottingham to make funeral arrangements. Despite Booth and his family visiting many northern parts of England, as well as going abroad William does not appear to have returned to his native Nottingham. However, Booth was extremely involved in the Army’s campaign against drink and prostitution. The nursery rhyme “up and down the city road, in and out of the Eagle” has its origins with Booth’s determination to stamp out alcohol. Booth wanted to purchase the Eagle and use it for a Salvation Army Meeting House.

In October 1890 Booth published his major social manifesto, 'In Darkest England and the Way Out'. He explored various far-reaching ideas, such as providing hostels, employment centres and helping young men learn agricultural trades before emigrating. His wife and long-term companion, Catherine, died from cancer.

In 1904 William commenced one of five motor tours around the British Isles, which ended in 1909 when he became so ill after surgery on his eyes. It is not certain whether he visited Nottingham on any of these tours. On 6 November 1905 he received the Freedom of the City of Nottingham, his home town, and a plaque in the Council House commemorates this. The following year he was also awarded the Freedom of the City of London.

He died on 10 August 1912 from complications after a cataract operation. At his funeral, 65,000 mourners passed by his coffin and 35,000 filled Olympia and 50,000 Salvationists marched six abreast behind the cortege. Booth’s Army by the end of the nineteenth century could be found in countries across the world and the membership could be counted in hundreds of thousands and continues today carry.

Thanks to the William Booth Birthplace Museum for help with this entry.