Berry Hill Hall in 2016.

Berry Hill Hall in 2016.The centre had first been decided on in 1922, when the Miners Welfare Fund of Mansfield Woodhouse joined with the Mansfield Committee project to acquire Berry Hill Hall with its 90 acre grounds for a convalescent home for miners. In 1932 the Nottingham Evening Post wrote that a scheme had been suggested to adapt the Hall, which had been used as a convalescent home for miners into a convalescent treatment home for the wives and children of miners.

The Berry Hill Hall Rehabilitation Centre, the first of its kind was established in Mansfield in 1939. It came into existence in April 1940 when it was opened by the Midland Colliery Owners' Mutual Indemnity Company in association with the Bolsover and Butterley Colliery Companies, and was at the service of the entire coalfield, which extended over seven counties. The centre was aimed at miners injured whilst working in the pits; for many years miners who were critically injured spent the rest of their life incapacitated and often were unable to work below or above ground. The Nottingham Journal commenting on the centre’s achievement in 1942 said, “…..the sights we used to see in mining villages, of men with injured spines and other fractures, becoming simply human derelicts, will not be allowed to reoccur, since these men can now reach practically 100% recovery.” 1 In a lecture to the Oxford Ophthalmological Congress in July 1915, Dr Frank Shufflebotham, a doctor and a medical referee in the workmen’s compensation system, pressed the case for increased interest on the part of the medical establishment in the causes and consequences of illness and injury among coalminers. “I do not think that sufficient attention has been paid by the medical profession…to the conditions of employment in this country…by those whom we have regarded as the leaders of the profession.” The speech, though focusing mainly on eye diseases, encapsulated an intensifying medical scrutiny of workers especially miners.2

The necessity for such an institution became even more desirable after the beginning of the Second World War when young men were conscripted to work in the coal mines of the United Kingdom, between December 1943 and March 1948, in order to increase the rate of coal production, which had declined through the early years of the war. The Bevin Boys, named after Ernest Bevin,3 chosen by lot as ten percent of all male conscripts aged 18–25, plus some volunteering as an alternative to military conscription, nearly 48,000 Bevin Boys performed vital and dangerous civil conscription service in coal mines, the final conscripts were not released from service until March 1948. Few chose to remain working in the country's coal mining industry after demobilisation. Many of these young men became the target of abuse as draft dodgers and deserters and unlike their military counter-parts, they were not given medals and their contribution was not recognised until 1995. Many of these men came from white and blue-collar work jobs and they were unused to the hard manual graft underground in mines in very cramped and hazardous conditions. Although they received training, nothing could prepare them for life and injuries underground.

Ernest Nicholl.

Ernest Nicholl.Colliery owners in the midlands had become aware that their injured workers were often treated inadequately, and Ernest Nicoll was asked to establish a fracture clinic at the local hospital. Known as Nick, Ernest Alexander Nicoll, was born 8 March 1902. He studied medicine at Cambridge University and St George’s Hospital, London, before going on to become consultant general surgeon in Mansfield 1931 and consultant orthopaedic surgeon in 1948. He was admitted as a New Fellow to the Edinburgh College of Surgeons in December 1934. His interest in trauma began in the 1930s after his appointment to Mansfield Hospital.

In April 1941 he wrote a paper for the British Medical Journal, “Rehabilitation of the Injured”. He argued that the word rehabilitation is an entirely different process for a person who has received injuries, rather than one who has been born with disabilities, from which the person needs to be cured or the disability needs to be reduced so that they may return to their previous work place; there was no really light work to offer disabled men. In the nineteenth century, many miners were ‘cured’ by having the problem amputated.4 The limited skills of some colliery surgeons and more general the inability of orthopaedics to carry out the complex repairs to limbs that came in the post-war period meant that amputation was often the easiest or indeed the only option.5 The rehabilitation problem in coal-mining was five times higher than the average industrial accident rate and in his work a miner who returns to full work has fully recovered. Over half of the cases in his fracture clinic, about 1200 a year, were miners injured at work. However, 87% resumed their full pre-accident occupation and 9% resumed lighter work in the same industry.6

The Miners’ Rehabilitation centre housed a gymnasium and a remedial workshop. It was not part of the local (Mansfield) hospital, which Nicoll believed had certain psychological advantages; patients who lived nearby could attend daily; those who lived further away, were under-nourished or whose home circumstances were unsuitable lived in. The treatment was intensive and aimed at each individual’s injuries. There were graduated remedial exercises, occupational therapy, physiotherapy and remedial games. However, perhaps more important, the gospel of rehabilitation was drummed into the patients – that recovery can only come by the unremitting hard work of the patient himself.

Nicoll believed that injuries had to be viewed both in terms of the broken bones but also the impact they had on the tissue, i.e. the muscle surrounding the bone, and unless the soft tissues were treated from the very beginning rehabilitation would become a salvaging problem. He said, “…the more one analyses disability the more one becomes convinced that the key to success is restoration of muscle power.” Mobility in his view was secondary, adding that to a miner diminished mobility with full muscle power gives a much better functional result than full mobility with diminished muscle power. Being able to lift weights off the ground is a vitally important part of the miner’s job especially if he is a coal-face worker. He emphasised that this could only be done by the unremitting efforts of the patient himself. Remedial exercises were the backbone of treatment, he suggested, but they must be performed against gradually increasing resistance, day in and day out using a system of pulleys and weights designed to determine muscle efficiency. The exercises were carried out for two periods of an hour and half each day. Dr Nicoll was in favour of passive movements, i.e. the patient helping himself to make movement, which flew in the face of the general thinking of the time. These remedial exercises had to be used in conjunction with other forms of treatment, such as occupational therapy, physiotherapy and remedial games; the first to gain ground and the secondary to consolidate it.

Occupational therapy and recreational activities were conducted both indoors and outdoors. Tasks such as work in the laundry and domestic cleaning, simple carpentry, the care of lawns and log-sawing were included. In order to get men back to ‘full’ working order they were given tasks such as operating a conveyer belt loaded with pieces of wood which helped in the use of their backs, as well as walking, bending and shovelling, all under supervision and giving the men time to pause occasionally. Games such as badminton, bowls and croquet as well cycling were all used to help the patient’s recovery. Physiotherapy was either rapidly alternating electric currents to stimulate nerve and muscle activity or deep massage.

The success of the centre led to the national programme of rehabilitation under the Miners' Welfare Commission, of which Berry Hill formed a part. Miners’ Associations from around Britain and abroad came to view the work carried out at the centre under the supervision of Ernest Nicoll. In August 1941 Warwickshire Miner’s Association came to inspect Berry Hall with the possibility of establishing a rehabilitation centre in Warwickshire.7 In 1942 and again in 1943 the Nottingham Journal reported that the pioneering work of Ernest Nicoll and successful experiments of the Berry Hill Hall had been the stimulus for the proposed erection of seven similar centres around Britain.8 The Yorkshire Post ran an article on injured miners at Berry Hill Hall, where one of the men commented, “They have done me a lot of good.” Another said, “The Centre is a grand thing for the miner. He gets the extra care and rest…”. 9 In 1945 he visited France and advised the French government on the development of rehabilitation for French miners.10 Following this visit in 1946 a French Medical Mission, who advised mining groups in the Pas de Nord and Pas de Calais coalfields visited the Nottingham area to see the work of the rehabilitation centre.11 In 1955 the Coventry Evening Post was reporting on the success of French doctors working miracles on miners using Nicoll’s rehabilitation ideas.12

The Berry Hill Hall Rehabilitation Centre had become regarded as one of the greatest centres in the country; compared with the treatment before the Second World War, the period of disability had been reduced remarkably and many men in the mining industry who had passed through the centre now had a far greater earning capacity than would have been possible if the rehabilitation service had not been established.13 Ernest Nicoll was often asked to speak to or accompany interested parties around the centre. In September 1942 a delegation visited the rehabilitation centre and saw 40 patients undergoing remedial treatment; one group who had compound fracture of the spine were playing netball. They were shown around by Ernest Nicoll and Guy de George Warren, managing director of the company. Later that year members of the Miners Federation were shown around by Nicoll and Warren. The visitors spoke to miners who were almost restored to their normal powers after severe pit accidents. 14

In 1947 and 1948 Nicoll visited the United States and Canada on behalf of the Miners Welfare Commission and the National Coal Board. His itinerary included New York, Chicago, Boston and Toronto. He addressed surgical meetings in San Francisco and Quebec.15

In September of the same year, he was to visit Amsterdam to take part in an International Congress on Orthopaedic and Traumatic surgery and was to address the Congress on behalf of Great Britain.16

In 1948 the Nottingham Evening Post reported that three ‘modern miracles’ had occurred at the centre. Lady Houldsworth, the wife of the chairman of the East Midlands Division of the National Coal Board, handed over three mechanically propelled invalid chairs to three miners paralysed as a result of spinal injuries sustained in the mine. One of them a Bevin Boy, Allan Wallace, whose legs were useless had managed to walk and could get around without crutches.17 In 1949 members of the east Midlands Group of the Institute of Public Administration were welcomed and shown around by Ernest Nicoll and given an insight into the remedial methods of treatment.18

In 1950, Dr Nicoll spoke to the Insurance Institute about the successful treatment men received and were able to regain full use of their limbs. He also showed a film he had made, called “They Live Again”, in which a miner is seen receiving treatment and then resuming his old work. He went on to advise the Miners’ Welfare Commission on the establishment of similar centres in the major coal fields throughout the UK.

Nicoll was awarded the CBE for his work with the rehabilitation centre in the 1950s. At the time he was surgical director of the Accident Services at Mansfield General Hospital, orthopaedic surgeon to the Chesterfield Royal Hospital and surgeon-in-charge at Berry Hill Hall.

Group of surgeons visiting from the Continent, with Mr Nicoll and Colin Chapple (bottom-right), at Mansfield General Hospital (early 1960s).

Group of surgeons visiting from the Continent, with Mr Nicoll and Colin Chapple (bottom-right), at Mansfield General Hospital (early 1960s).With the advent of the NHS Nicoll became a consultant orthopaedic surgeon continuing his work with trauma. He later became the first director of postgraduate education for the Sheffield Regional Hospital Board and Sheffield University. He died from bowel cancer on 3 October 1993. The Berry Hill Hall centre carried on its work until 1988.

A Grade II listed 18th century building, the Hall was sold in 1994. Blackthorn Homes bought the dilapidated hall in 2003 and worked alongside conservation and planning officers and councillors from Mansfield District Council on the £30m restoration to restore the 250-year-old buildings to their former glory, including a clock tower and the front of the hall.

It is of interest that the major rehabilitation centre for returning war casualties is now in Nottinghamshire, at Stanford Hall, near East Leake.

1. Nottingham Journal, 11 December 1942

2. Kirsti Bohata, Alexandra Jones, Mike Mantin, and Steven Thompson, Disability in Industrial Britain : A cultural and literary history of impairment in the coal industry, 1880–1948, Manchester University Press (2020). p. 64

3. The programme was named after Ernest Bevin, a former trade union official and then British Labour Party politician who was Minister of Labour and National Service in the wartime coalition government.

4. Disability in industrial Britain, p. 74

5. Disability in Industrial Britain. p. 74

6. E A Nicoll, BMJ, Rehabilitation of the injured, 5 April 1941, pp 501-506

7. Tamworth Herald, 30 August 1941

8. Nottingham Journal, 11 December 1942 and 13 August 1943

9. The Yorkshire Post, 16 April 1943

10. Mansfield Advertiser, 6 January 1950

11. Nottingham Evening Post, 22 October 1946

12. Coventry Evening Telegraph, 6 May 1955

13. Nottingham Journal, 12 July 1946

14. Nottingham Journal, 24 September 1942 and 11 December 1942

15. Mansfield Advertiser, 6 January 1950

16. Mansfield Advertiser, 23 April 1948

17. Nottingham Evening Post, 22 October 1948

18. Nottingham Journal, 12 March 1949

Structural

Berry Hill Hall, c.1800.

Berry Hill Hall, c.1800.The house was built in the early 18th century, extended c.1770 and a symmetrical front with a pedimented entrance bay added in the early 19th century. The house has been converted to flats.

A stable block surmounted with a polygonal tower was built in the late 18th century.

The Listed Building description is available on the Historic England website.

Cartographic

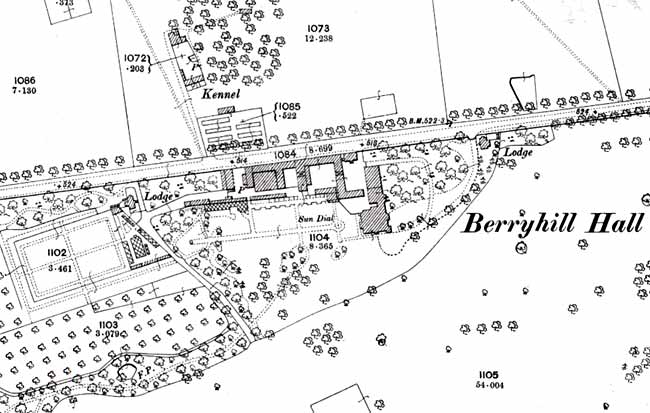

Ordnance Survey map of Berry Hill Hall dated 1898. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.

Ordnance Survey map of Berry Hill Hall dated 1898. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland.A wide range of Ordnance Survey maps from the 1840s to the present day are available at Nottinghamshire Local Studies Libraries and Nottinghamshire Archives. The earliest large scale (25" and 6” to the mile) coverage dates from the 1870s and an online digital archive of these maps for the whole county is accessible through the Old Maps and National Library of Scotland websites:

Graphic

There are 21 photographs of Berry Hill Hall on the Inspire Picture Archive website, 2 images on the Picture Nottingham website and 1 photograph on the Picture the Past website.

There is a film (shot in 1944) available on the British Council website that 'depicts the service provided for injured miners at a well-known hospital and rehabilitation centre in the Midlands. All stages of the treatment of severely injured miners are shown, also the principles underlying rehabilitation.' It is believed the rehabilitation centre is Berry Hill Hall:

Archival

Nottinghamshire Archives hold a small number of documents relating to Berry Hill Hall. Details available on the online catalogue.

Printed

Kirsti Bohata, Alexandra Jones, Mike Mantin, and Steven Thompson, Disability in Industrial Britain : A cultural and literary history of impairment in the coal industry, 1880–1948, Manchester University Press (2020)

E A Nicoll, 'Rehabilitation of the injured', British Medical Journal, 5 April 1941, pp 501-506

'E A NICOLL CBE, MD, FRCSED [obituary]', British Medical Journal, Volume 307, 4 December 1993, pp 1490-1