Overview

Bromley House

The idea for a library in Nottingham was conceived in December 1815 when the solicitor John Pearson wrote to the Duke of Newcastle announcing plans to establish a public library and newsroom. Mr Pearson also wrote to other prominent people including John Smith, MP.

The Duke of Newcastle gave his permission in the hope that ‘such an establishment may be a benefit and convenience to the town and neighbourhood of Nottingham’ and on the understanding that ‘it will be in no way political’.

John Smith also added his comments:

I believe that it is the recollectn of several of my friends in Nottingham that I have frequently lamented the want of an establishment of this nature from which in other Towns particularly Liverpool and Belfast the best consequences have arisen. The object has my most cordial approbation, and I beg your permission that my name may be admitted among those of the subscribers

On the 2nd April 1816 at a crowded meeting at Thurland Hall in the centre of town, the home of Dr John Storer, the Nottingham Subscription Library was formed. It was financed by the purchase of a share, at ten guineas and an annual ‘subscription’ of two guineas, the subscribers writing their names at the bottom of the rules, hence the term.

Membership covered the family, and as such is, in the way of the 19th century, predominantly in the name of the man as head of the household. Women could be members in their own right, however, with around ten per cent of the original subscribers being female, generally described as spinsters or widows. They had full voting rights in the new institution, but a special rule allowed them to appoint a proxy to vote on their behalf. As the membership covered all resident family members, this also included any servants who resided in the house, a curious quirk that technically still applies today.

This new library started by forming a committee, appointing a librarian and devising the rules, the fines being a major component of these. It is easy to imagine the fines would be eagerly enforced by the Librarian, as he was allocated a quarter of these. His annual salary was ‘from £30 to £40 ‘and he was ‘provided with proper apartments for his residence at the Library, free from rent and taxes’.

The Library opened on 1st July 1816 in premises on Carlton Street for ‘reviews and magazines alone’ and a book was provided for subscribers to propose books. Initially, the Committee agreed to spend £100 (around £4000 today) on books but in July 1816 they added a further £500 (around £18,000 today) and the Library opened for ‘the delivery of books to the Subscribers’ on 28th October 1816.

Bromley House frontage in the early 1900s. The basements were rented out to many different tenants, mostly basket makers or wine sellers.

However, by 1820 the Library was running out of space in the Carlton Street premises. At a Special General Meeting in April 1820 it was decided to purchase Bromley House, which had come up for auction. William Stretton, Edward Staveley, and John Pearson formed a sub-committee to attend the auction and were to bid no more than £3000. They bought the property for £2750.

The money to buy Bromley House came from several places. A loan of £1,700 was raised from Smith’s Bank, £669 was raised through selling off property on St James’s Street, and the rest was raised through the issuing of £25 loan shares. The loan shares were slowly bought back and had been paid off within 35 years.

The 1822 annual meeting resolved that a trust would be set up to hold Bromley House ‘for the time of 5000 years for the general benefit of the present subscribers’. This continued until 1924 when the Library became a limited company with a board of directors. This changed again in 1995 when the Library gained charitable status. Members no longer had to buy a share and the Library officially changed its name from Nottingham Subscription Library to Bromley House Library, a name it had informally used since 1822.

With new premises, the Library could now make money from more than just the subscribers. At the 1822 annual meeting, it is noted that the Library was renting out rooms to the Newsroom for £40, the Billiard room for £30, the Musical Society for £10 10s, and the cellars for £19 14s.

On 19th July 1841 Alfred Barber applied to the Library to set up a Photographic Institution in two attic rooms. He was granted permission at a rate of £8 per annum. He was using daguerreotype photography, a process patented by Daguerre in 1839 in Paris and licenced for use in the UK by Richard Beard. Alfred Barber installed, at his own expense, a revolving skylight in the roof of the south attic so that he always had the best light no matter what time of the day it was and he charged patrons one guinea to have their photograph taken. Unfortunately, Mr Barber did not make money from taking photographs and shut up the studio in January 1843, although his rent had only been paid up to July 1842. He was being sued by Richard Beard for failure to pay for his licence and Alfred Barber was countersuing as he had been promised that he would make his fortune. Alfred eventually escaped his creditors by fleeing to the Channel Islands, where the licence didn’t apply. Alfred did eventually return to the UK mainland, still taking photographs in Winchester, Reading, and finally ending up in Bristol.

Taking photographs in Bromley House may not have made Alfred Barber any money but others managed to succeed and from 1845 until 1955 the studio was in almost constant use.

Other tenants over the years have included a Ladies Branch Bible Society, a Medical Society, a Literary Society, a Law Society, a Picture Gallery, a Chess Club, a Natural History Society, an amateur Musical Society, the Bell Inn Florist Society, and the Thoroton Society.

Several of these tenants caused trouble for the Library. In 1832 and 1833 the Billiard Society were reprimanded several times for the ‘repeated firing of guns and pistols in the garden and billiard room’ and for the ‘disorderly conduct’ of the members.

In 2013 the whole of the Meridian Line was exposed for the first time in over 100 years. Photo © Frances Potts

Another one was the Natural History Society. They started meeting at the Library from 1836 until 1842. They originally rented the back half of the Newsroom and one of the attics, however having rooms on the ground floor and fourth floor did not suit the society and in December 1836 they were requesting to move to a suite of rooms on the second floor. By March 1837 they were renting out the Billiard room and the Literary Society room in the wing of the building for £30 a year. However, by 1838 tension between the Society and the Library was growing. A Special Committee meeting was called in August 1838 as the Natural History Society wanted to allow access to the members of the Nottingham Mechanics Institute to see their museum. This was objected to by the members of the Library committee and they went as far as to draft a notice for the Natural History Society to quit the premises if they allowed members of the Mechanics Institute to enter the premises again.

It seems that the Natural History Society acquiesced to the committee’s demands but by 1842 the Society had moved out to the Mechanics Institute, taking with them the collections that had been kept at the Library.

Despite the loss of the Natural History Society, the members of the Library had a keen interest in science. Before the Natural History Society rented rooms in Bromley House, the Library started its own Mineralogical and Geological Society in 1818. The Library was also furnished with scientific equipment, such as a barometer, a thermometer and a pair of 18 inch globes bought by the Library in 1821. A wind dial was procured in 1822 and a clock was donated by Mr Staveley in 1821 until the Library had the funds to purchase its own. In 1836 a sundial was donated by the Reverend Robert White Almond, who was the President of the Library from 1819 to 1853. White Almond studied mathematics at Cambridge and was a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society as well as being the rector at St Peter’s Church Nottingham for 37 years. It was probably due to his influence that a meridian line was laid in the Library. This is a mechanism for setting clocks to the right time using the sun. In 2013 the whole of the line was exposed for the first time in over 100 years.

This portrait of the Reverend Robert White Almond hangs in the Library. Photo © Frances Potts

The Reverend Robert White Almond was not the only mathematician in the membership of the Library. In 1823 George Green joined the Library. As a miller’s son, George had one year of formal schooling at the age of about 8 or 9 and went to work in his father’s mill in Sneinton (now Green’s Windmill and Science Centre). In 1823 he joined the Library and it was here that he encountered books on mathematical ideas that were not usually taught in England, such as Laplace’s Celestial Mechanics. In 1828 George Green published his first essay: An Essay on the Application of Mathematical Analysis to the Theories of Electricity and Magnetism. This work was privately published and most of the subscribers were members of the Library. It was also through the encouragement of the Library members that George Green eventually attended Cambridge University at the age of 39. It is also rumoured, although no evidence exists to back up the claim, that George Green helped to lay the meridian line in the Library.

To run an institution such as the Nottingham Subscription Library required a committee to deal with the day to day running of the Library. The committee was the final arbiter of disagreements and rule breaking. The committee minutes are littered with references to members breaking or abusing the rules of the Library and the committee’s response to them. In 1822 Mr George Freeth had to be advised that while country members (who were classed as people who lived more than 1 mile away from town) could apply for permission to borrow books for longer than the set time, unfortunately his residence on Standard Hill did not qualify him for such an extension as it was only quarter of a mile away.

This notice was placed in the Library to remind members of one of the rules. Photo © Frances Potts

In 1829 members had to be told that dogs were not allowed in the Library, as members were tying them to the bottom of the staircase in the hallway. This was introduced when two dogs were tied at the bottom of the stairs and a fight ensued. Members had to be reminded again in 1835.

We have a rule in the Library that members are not allowed on the roof of Bromley House. This rule dates from the 1826 when members were told they were not allowed on to the roof without the permission of the committee. A few months after this rule was decided some members asked for permission to go onto the roof to watch Mr Green launch his hot air balloon in the Market Square. Permission was denied by the committee on the basis that the rule could not be broken and members were not allowed on ‘the roof or in the rooms above the Library’.

Children have always been allowed in to the Library but their presence has caused some consternation amongst the membership. Children have been admonished for taking books off the shelves, running in the garden, and a notice was displayed reproaching all children who had committed the crime of reading the new books. In 1849 a baby was abandoned in the Library. This caused great debate amongst the committee. Not, as you might expect, because they were worried about the child and the mother, but because the boundary between the parishes of St Peter’s and St Nicholas’s runs through the Library and it had to be decided on which side the baby was found so that the right parish could take responsibility for the baby.

James Bishop wasn't the only problem member of the Newsroom. This notice was placed in the Library at the request of the Newsroom members. The paper had been removed for half an hour by Robert Hepburne, who promised never to do it again. He was allowed to remain as a member. Photo © Frances Potts

However, some problems were too great even for the committee. James Bishop caused problems in the Newsroom due to his ‘infirmities’. On being asked to discontinue his visits to the Newsroom, Mr Bishop refused and the Committee resolved that if he continued his visits ‘a Police Officer be directed to attend and remove him’.

The person who had to deal with such members on a day to day basis was the Librarian. While many worked hard during their tenure at the Library, some became embroiled in scandal.

In July 1834 James Archer was brought before a special meeting of the Committee as he had absented himself and ‘conducted himself in a highly improper manner’ and he was found to be ‘unfit to retain his office’.

In 1893 John Banwell was the subject of a Special Committee Meeting, the first to be held outside of Bromley House since 1820. The proposed motion was 'that it is desirable to remove Mr Banwell from the office of Librarian'. No reason for this drastic step was given, nor did one later emerge.

J. William Moore worked for the Library for 33 years, first as Assistant Librarian then as Librarian for the last six years. Despite regular increases of salary and holiday allowance, it became clear that £103 18s 2d was missing from the accounts. Mr Moore had kept the money from five shares which he had sold. While Mr Moore had written a letter admitting to his embezzlement, he was never prosecuted and it appears that the money was never recovered.

His immediate successor, Arthur Lineker, also served for a long period as both Assistant Librarian and the Librarian. Mr Lineker was a keen photographer, setting up a dark room in what is now the Safe Room, and providing many of the photographs for the 1916 history. He is also responsible for modernising the Library by introducing a typewriter in 1902. He used this to type out the card catalogue, used by the Library until 2011. From 1909 he was stopped from selling shares, perhaps because of irregularities and in 1926, after contracting scarlet fever, he was dismissed for misappropriation of funds.

But the perennial issue with the staff of the Library can be summed up by a member’s suggestion written in the 1890s:

Mrs Allcock humbly suggests that the Sub-librarian be sent to a night School. The handwriting on the covers of the magazines is a disgrace to the N.S.L.

Photo © Frances Potts

The year 2016 has seen the 200th anniversary of the opening of the library and it continues to thrive but still keeps the essence of the ideas laid down at the first meeting in April 1816. The words of Marcus Tullius Cicero are still relevant today as they were 200 years ago:

‘If you have a library and garden, you have everything you need’

Structural

Regarded as 'Nottingham's finest C18 town house' Bromley House was built by George Smith, grandson of the founder of Smith's Bank. There are two date stones in the garden walls that read '1752 GS'. The building has a five-bay front and is of three stories with attics. There are shop fronts either side of the front door that were inserted in 1929. Harwood (2008) provides a detailed description of the house.

Cartographic

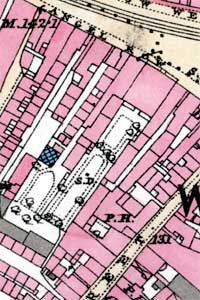

The 1st edition 25" to the mile Ordnance Survey map of Nottingham showing Bromley House in 1881. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

Large scale Ordnance Survey maps from the late 19th and early 20th centuries show the town in great detail:

- 1:2500 (25” to the mile) and 1:10560 (6” to the mile) published in 1884 (1st revision in 1898; 2nd revision in 1915)

- 1:500 (10 feet to the mile) published 1884 in 10 sheets

These maps can be consulted at Nottinghamshire Archives or the local studies sections at Nottingham Central Library or Worksop Library.

Online digital archives of these maps are accessible through the Old Maps, National Library of Scotland and Nottinghamshire Insight Mapping websites:

Graphic

The are over 30 photographs relating to Bromley House on the Picture the Past website.

Archival

Bromley House Library holds its own archive collection.

Printed

[Robinson, E. and Wilson, J.], Bromley House: The Garden, [Nottingham Subscription Library], [1996], [4] p.

Coope, R. T. and Corbett, J. Y. (editors), Bromley House, 1752-1991: Four Essays Celebrating the 175th Anniversary of the Foundation of the Nottingham Subscription Library, Nottingham Subscription Library, 1991, 137 p. Illustrations. Contents: 'Nottingham Subscription Library: Its Organisation, Its Collections and Its Management Over 175 Years', by P. A. Hoare, [1]-47, 131-134; ''The Best Built House in Town'', by F. N. Hoskins, [49]-75, 135; ''Grumbly House'': Aspects of the Administrative and Social History of the Library', by S. N. Mastoris, [77]-100; 'The Photographic Studio', by P. F. Heathcote, [101]-130.

Hall, H. C., 'Bromley House Library, Nottingham', Nottingham Observer, 6(41), 1959, 46-47.

Harwood, E., Pevsner Architectural Guides : Nottingham, Yale University Press, 2002, 59-60

Russell, J., A History of the Nottingham Subscription Library, More Generally Known as Bromley House Library, Nottingham: Derry & Sons, 1916, 127 p. Available online at the Internet Archive