Overview

Portrait of Dr Robert Thoroton (1623-78) (image courtesy of Sir Robert Hildyard).

Portrait of Dr Robert Thoroton (1623-78) (image courtesy of Sir Robert Hildyard).Origins and upbringing

Robert Thoroton was born at 6.15 am in the morning of 4 October 1623, the eldest of six children born to Robert Thoroton (1601-1673) of Car Colston and his wife Anne Chambers of Stapleford. Thoroton’s parents had been married by licence at St Mary’s Church, Nottingham, on 30 November 1622. Thoroton’s mother died in 1660, when he was in his late thirties, but his father, Robert senior, lived until his early seventies, dying in 1673, only a few years before Thoroton himself. Whilst four of Thoroton’s siblings had their baptisms recorded in the Car Colston parish register between 1627 and 1636, neither Thoroton nor his sister Elizabeth are recorded as having been baptised in St Mary’s church.

Thoroton was descended from a family which derived its surname from the neighbouring village of Thoroton – originally ‘Thurveton’ – a Viking name meaning ‘Thurfrith’s farm’ – where they owned land in the late 1300s. The family inherited property in Screveton and Car Colston through marriage into the Morin family around the year 1500. The Morins had themselves inherited property from the Lovetot family, Norman barons who had founded Worksop Priory.

It is likely that Thoroton was educated privately by local tutors during the 1630s. These tutors probably included Gilbert Radford from neighbouring Thoroton and Thomas Stacy of Car Colston. In December 1639, Thoroton entered Christ’s College, Cambridge as a sizar. A sizar was a working undergraduate who received allowances for work undertaken in the college. Thoroton graduated with a BA in 1642/3 and MA in 1646, being listed amongst 120 students. He also studied medicine and was granted a university licence to practice medicine in 1646. He does not appear to have undertaken any clinical training, but was examined by Dr Francis Glisson, the Regius Professor of Physick at Cambridge, and a member of the Faculty of Medicine.

Seventeen years later, in 1663, Thoroton was granted a Lambeth Doctor of Medicine largely as the result of his close friendship with Gilbert Sheldon, the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1663 to 1677. Sheldon had become acquainted with Thoroton’s family when he lived with the Hackers of East Bridgford during the Civil War. It was largely as a result of Sheldon’s patronage that Thoroton was awarded his honorary doctorate in medicine, on the grounds that his studies had been interrupted by the ‘unhappy distractions’ of the Civil War.

The Civil War had broken out in 1642, when Thoroton was nineteen, and continued throughout the period that he was studying at Cambridge. As such, it is unlikely that he personally knew either John or Lucy Hutchinson, recorders of detailed Memoirs of the course of the war in the county, not least because of their different political sympathies; the Hutchinsons being parliamentarians and the Thorotons ardent royalists. Thoroton later recalled seeing the second siege of Newark in 1644 when ‘Prince Rupert took a goodly train of artillery…together with their foot arms, when he so fortunately relieved the town’. Thoroton may have watched the procession marching up the Fosse Way, which formed a boundary with his family’s land. Thoroton also recorded that, during the third siege of Newark in 1645-1646, the ‘town suffered more by the plague within than the enemy without’. This would have been particularly memorable for Thoroton, given that his great grandfather was one of fifty plague victims who had died at Car Colston in 1604.

Politics, marriage and medicine

Politically, Thoroton was a conservative – even a reactionary - in matters of church and state. He upheld the values of the monarchy, the landed aristocracy, and the established Church of England, and was keen to advance his family’s claims to gentlemanly status and noble connection. When he petitioned for his Lambeth doctorate in 1663, Thoroton claimed he had been ‘a very great sufferer for his loyalty to his Majesty and his obedience to the Church of England’ during the Civil war and had consequently been much ‘impaired in his estate’. When Thoroton was granted a crest to add to his coat of arms, the following year, the newly minted Dr Thoroton was described as ‘a person of antient family in these parts, but for his learning and prudent deportment generally notified to be well deserving of his country’.

On 27 October 1645, Thoroton married Ann Boun (or Bohun), possibly at Newark. Anne’s father, Gilbert, held property at Hockerton and at High Pavement in Nottingham. He was a lawyer and tax collector who served as a sergeant at law and Recorder, but suffered for his Royalist views, and took refuge in Newark during the Civil War. He lived to see the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, dying in 1662/3, and was survived by two sons and three daughters. However, he became impoverished by the fines levied upon his property during the Commonwealth government, between 1650 and 1660, and such was his reduced financial status by the end of his life, that Thoroton later assumed financial responsibility for maintaining his two sisters-in-law, Barbara and Millicent.

Thoroton had three children with his wife Ann. All of them were girls. Anne was born in 1650, Elizabeth was born in 1654, but the middle child, Mary, who was born in 1652, accidentally drowned, possibly in the ornamental pool in Thoroton’s garden, and died in 1655. They were all were baptised at Car Colston.

Following his mother’s death in 1660, Thoroton lived with his father in the old family home, Morin Hall, facing the Little Green at Car Colston. The Hall, together with an adjacent property known originally as Toke Place, and later as Brandreth Farm, had been inherited by the Thorotons from the Morin family. In 1666, it had become so ruinous that Thoroton pulled it down and built a new brick house next door. The hearth tax records show that the property was enlarged from five to ten hearths and later sales catalogues suggest it had about a dozen principal rooms, supplemented by kitchen, closet and subsidiary spaces. The work was probably funded by the reluctant sale of some of Thoroton’s hereditary family land. In 1660, Thoroton sold about fifty acres of land to Dr Brunsell of Bingham, who proceeded to build Brunsell Hall at the east end of Little Green in Car Colston. The sales may have been necessitated by the financial problems of Thoroton’s father-in-law, Gilbert Boun, and Thoroton’s growing responsibilities as a local physician and landowner. Even after the sales, Thoroton and his father continued to enjoy the occupation of about eighty acres of land, whilst a further forty acres was leased to tenant farmers.

During the 1660s, Thoroton established himself as consultant physician to the gentry and to a wide range of professional patients living in Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire and Derbyshire. The position entailed tact and diplomacy, with Thoroton often being called upon to act as a go-between in family arguments or asked to give legal evidence in lawsuits involving disputed wills and inheritance. Such were the vagaries of travel and communication in the period, that Thoroton was frequently driven to dispense medical advice by personal correspondence rather than actual physical examination of the patient. This could sometimes lead to plaintive letters from his patients. In 1669, George Cartwright of Ossington Hall, informed Thoroton that:

I have drunk one bottle of the tincture and have begun on the second. Tomorrow, I intend to take four pills and as soon as I know how to take the ‘snayl water’ I will take your directions. I am not yet able to go down the stairs and feel some pain in my knees, which makes me fear the next full moon…If your more urgent business would permit it, I would be glad if you would yourself take a better account of your crazy patient and humble servant George Cartwright.

The Antiquities of Nottinghamshire

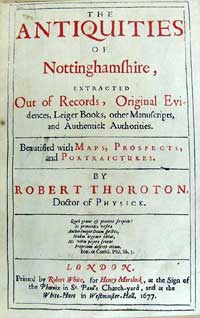

Title page of the 1677 edition of 'The Antiquities of Nottinghamshire'

Title page of the 1677 edition of 'The Antiquities of Nottinghamshire'Alongside this professional activity, Thoroton was developing his interest in documenting local and family histories. This seems to have begun as a pastime, mainly used to trace the manorial descent of each place in Nottinghamshire and the gentry families who lived in them. By visiting churches and country houses and consulting numerous archives, he amassed enough material for a book.

The research for what later became Thoroton’s Antiquities of Nottinghamshire was spread across the period from 1662 to 1675. It drew upon work undertaken by his father-in-law, Gilbert Boun, for a description of Nottinghamshire manors for taxation purposes, as well as the results of Thoroton’s own visits to churches, largely in the centre and south of the county, to make inscriptions from tablets, memorials and gravestones, and to take copies of coats of arms. He was largely reliant on correspondence for information from the north of the county. Thoroton also borrowed archives from leading members of the nobility and gentry. This gave him access to the cartularies (the deeds or charters registering titles to the property of an estate or monastery) of Rufford, Newstead, Blyth and Thurgarton. He borrowed the Southwell Chapter records and consulted the muniments and archival remains of many landed families, no doubt gaining entry by way of his professional connections as a consulting physician. However, Thoroton never visited national repositories such as the public records in London and the diocesan records in York, and this led even friendly commentators, such as William Dugdale, to qualify their praise of his work. ‘I do esteem the book well worth your buying’, Dugdale later told a friend ‘though had he gone to the fountain of records it might have been better done’. This was in spite of the fact that Thoroton had pre-empted criticism of his book with the closing observation, ‘I allow no man for a judge who has not attempted the same himself’.

But Dugdale had ‘attempted the same himself’, having already published his Antiquities of Warwickshire in 1656. It was Thoroton’s acquaintance with Dugdale, the Garter King of Arms, which was to transform his private antiquarian research into a major work of scholarly reference and the first published history of Nottinghamshire. In 1663, the College of Arms undertook a Heraldic Visitation of Nottinghamshire to ensure that no-one was using unauthorized coats of arms or pretending to be a ‘gentleman’. This was especially important, given that it was only three years since the restoration of the monarchy. As chief herald of the College, Dugdale consulted Thoroton, and employed him to compile or edit about a dozen pedigrees of local families. The following year, Dugdale encouraged Thoroton to turn his Nottinghamshire research into a book. Thoroton agreed, observing that, having acted as a doctor, but ‘not being able for any long time to continue the people living in it’, he was now going to ‘practice upon the dead’ and record their family histories instead.

It was also Dugdale who approved the addition of a crest to Thoroton’s family coat of arms, which had been granted on 23 August 1662. The crest, registered in 1663, added a lion rampant holding a bugle horn. Bugle horns were associated with military service and were distinguished from hunting horns which did not have ribbons attached. The crest recalled the Thoroton family’s ancestral links with the Lovetots and provided the emblem from which the Thoroton Society’s own logo is derived to this day.

Thoroton was now clearly entrenching his social position within the county. He was appointed a county magistrate in 1670, probably as a result of recommendation by his friend, Archbishop Sheldon. It was an unusual honour for someone who was not one of the country gentry. Thoroton was assiduous in his attendance of the magistrates' bench and was particularly noted for the severity with which he policed religious nonconformity and dissent. In the mid-1670s, Sheldon issued instructions to county magistrates to break up meetings of nonconformist bodies, and Thoroton gained notoriety within Nottinghamshire for his hard-line persecution of them. He was particularly opposed to Quakers, because they defied any attempts to regulate their conduct, and refused to take oaths of loyalty to the Church or the Monarchy. Indeed at the time of his death he had been summoned by the Privy Council to answer for the disruption caused to village communities by his excessive diligence.

Thoroton’s The Antiquities of Nottinghamshire was published in London in 1677. It is a very detailed and fully indexed study, illustrated with engravings of country houses, churches, family monuments, fine illustrated views of Nottingham and Newark, and drawings of the coats of arms of numerous local gentry families. He worked with Richard Hall, a Nottingham heraldic and monumental mason, on the drawings, which were engraved, through Dugdale’s influence, by the noted Bohemian exile, Wenceslaus Hollar. The book was printed by Robert White for Henry Mortlock ‘at the sign of the Phoenix in St Paul’s churchyard, London, and at the White Hart, in Westminster Hall’, and sold for between 16 and 18 shillings a copy. Mortlock was probably the brother of John Mortlock who was a bookseller in both Nottingham and Newark at this period.

By the time that Thoroton’s Antiquities were published in 1677, he had established the future of his family through the marriage of his two daughters. Elizabeth was married in 1672, to John Turner, a wealthy nouveau riche coal master from Swanwick in Derbyshire, whilst Anne was married, in 1673, to Philip Sherard of Whissendine, Rutland, the grandson of William, Baron Leitrim in the Peerage of Ireland. The marriages symbolised the liminal status in which Thoroton sat, in terms of social classification – poised somewhere between aspirations to nobility and gentry status, on the one hand, and well-developed connections with trade and the professions, on the other. Yet the long-term fortunes of the family were better served by Elizabeth’s marriage to the coal master John Turner than Anne’s marriage into the Irish nobility. After his death in 1678, Thoroton’s estate passed to his two daughters and their husbands. Meanwhile, Thoroton’s younger brother, Thomas (1636-95), a wealthy corn chandler from London, purchased the neighbouring Kirkton estate in Screveton, barely two miles away, in 1685. Ultimately, both the daughters’ lines ran out of heirs and the Car Colston property was reunited with the Thoroton family, with their seat at Screveton, in 1789. However, the family immediately sold off the Turner’s mineral rights in Derbyshire, in order to purchase Flintham Hall for £16,000, as their new family seat. The last of the Thoroton line married into the Hildyard family of Winestead, in Holderness, Yorkshire, ancestors of the current owner of Flintham Hall, Sir Robert Hildyard.

The Thoroton Society

Thoroton died on 21 November 1678, aged 55, having lived to see the publication of the Antiquities the year before. Over two centuries later, in June 1897, a meeting in the Grand Jury Room at Shire Hall in Nottingham, unanimously agreed to name the County’s newly formed Historical, Archaeological and Antiquarian Society in honour of Nottinghamshire’s first historian, Dr Thoroton. The suggestion was that of W.P.W. Phillimore, who was the principal founder of the Thoroton Society. The following month, the first Society excursion took in Thoroton country, centred on Car Colston and its neighbouring villages. On Tuesday 27 July 1897, fifty members met at Bingham station and proceeded to Car Colston, Screveton, Hawksworth and Thoroton. They moved on to Aslockton, Whatton-in-the-Vale (for lunch), Langar, Wiverton, and arrived back at Bingham in time for the first of what has turned out to be a Society tradition – the Thoroton tea. The following morning, they toured the historic sites of Nottingham, moved on to Wollaton in the afternoon, and finished with a lecture at the Albert Hall on ‘The Early Churches of Nottinghamshire’ and W.P.W. Phillimore’s clarion call to the Society, entitled ‘The work we have to do’. 125 years later, the Society continues to honour the name and work of its eponymous founder, and to maintain the high standards of scholarship for which he was known in his lifetime.