The Luddites

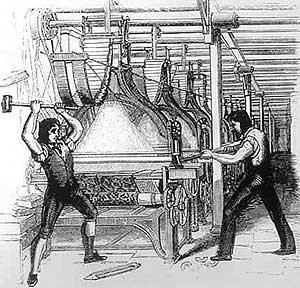

An early 19th century engraving showing frame-breaking in progress.

Luddites was a term given to frame breakers, in the years between 1811 and 1817. It was coined around the mythical figure of Ned, or General Ludd, who was named as the leader of the disturbances. Subsequently the term has come to refer to anyone or any group of people who oppose the introduction of new machinery, or new technical equipment.

Frame-breaking has a long history, but it was usually associated with industries where new technology was undermining the livelihoods of those who worked the old machines. This was particularly the case in the Luddite disturbances, where groups of workers sought to maintain their own employment by damaging, or destroying, new machines which were faster and more efficient, and as a result led to a price war.

The first disturbances associated with Luddism occurred on 11 March 1811 when a group of Nottingham framework knitters assembled in Arnold, beyond the town boundaries, and destroyed 63 frames ‘belonging to those hosiers who had rendered themselves the most obnoxious to the workmen’. No other damage was done and no violence was reported. The key points were that the frames which were damaged were wide frames, and they were usually worked by ‘colts’; in other words they were frames on which cut-ups were made, which were cheaper but not fully fashioned on the machine and so of an inferior quality; and were worked by people who had not served the traditional seven year apprenticeship, known as colts.

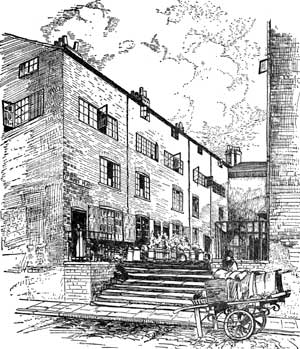

Framework knitters' housing in Nottingham.

The framework knitters were not fundamentally opposed to the wide frames or the colts, but they were when employers continued to rely on them during a trade depression. In these conditions the knitters wanted the employers to lay off the colts working wide frames, in order to protect the skilled workers operating the old narrow frames, until times improved. For their part, the employers were suffering as much in the trade depression as the knitters, and they wanted to maximise output in order to keep up their sales income.

John Blackner, in his History of Nottingham (1816) referred to the events of 11 March as a form of direct action to take ‘vengeance upon some of the hosiers, for reducing the established prices for making stockings, at a time too, when every principle of humanity dictated their advancement’.

Between 16 and 23 March 1811 more than one hundred frames were broken in Sutton in Ashfield, Kirkby in Ashfield, Woodborough, Lambley, Bulwell and Ilkeston, and other attacks followed in Mansfield and Bulwell.

A handbill of 26 March 1811 produced by Nottingham corporation, offered a reward of £50 to anyone supplying information about frame breakers, referred to them simply as ‘evil minded persons’ who had ‘assembled together in a riotous manner’.

At this stage, the movement was amorphous and leaderless, and even the word ‘movement’ possibly suggests a level of organisation which simply did not exist. It was also covert, in that it took place by night, frame breakers covered their faces to avoid recognition, information was spread entirely by word of mouth, the frame breakers having done their job dispersed into the night, and the authorities neither knew who or what they were trying to apprehend. Nor did they have any success at all in identifying participants.

The disturbances seemed to have fizzled out by the end of April 1811, but they started again on 4 November 1811 when six frames were smashed in Bulwell. For the first time, Ned Ludd appeared as a name on threatening letters. Ludd, subsequently promoted to ‘General’, was by repute an apprentice stocking frame knitter. Blackner recorded in 1816 that he was ‘an ignorant youth, in Leicestershire, of the name of Ludlam who, when ordered by his father, a framework-knitter, to square his needles, took a hammer and beat them into a heap’. William Nunn, a Nottingham lace manufacturer, reported to the Home Office in London on 6 December 1811 that ‘many hundreds of letters have been sent signed “Ludd”, threatening lives and to burn and destroy the houses, frames and property of most of the principal manufacturers’.

An imaginary portrait of "The Leader of the Luddites" published in 1812.

Ludd was never a single real person. The term referred to a leader, and could be assumed by anyone leading a group of frame breakers. Contemporaries often used fictitious names like this to ensure that they retained anonymity. So letters in the name of Ludd were circulated to indicate to recipients where they had come from without giving away any particular people.

On 10 November 1811 the movement took a sinister turn when John Westley of Arnold was shot dead during a disturbance in Bulwell. His fellow Luddites first removed his body to a safe distance, before returning to the workshop and, ‘with a fury irresistible by the power opposed to them’, smashed the frames, while the so-called guards all ran away. Another 10 or 12 frames were smashed at Kimberley the same evening, on this occasion because the owner had ‘the habit of learning colts: that is, he had learnt persons to make stockings without their serving a regular apprenticeship to the trade’.

Over the following days there were numerous outbreaks of frame breaking, and troops were summoned, together with the militia and yeomanry cavalry to try to establish order, without a great deal of success.

On the night of 23-24 November Luddites broke 30-34 frames at various workshops in Basford, and one frame in Chilwell. In Basford ‘the ironwork of [the broken frames] was broken into pieces and scattered in all directions’. On 25 November eleven frames were broken in Eastwood during the afternoon, and others in Trumpet Street and York Street in Nottingham, in Cossall, Heanor, Arnold and elsewhere.

The Luddites worked by night, and they assembled at pubs or other known meeting points. As such they were always one step ahead of the authorities, so that no arrests were made: ‘anonymous threatening letters are continually received by the Magistrates without detection, and the Military are likely to be harassed by misinformation, and are themselves unequal to meet the evil, unless some collateral assistance can be afforded.’

Police specialists, known as Bow Street runners, were sent from London to assess the situation and to offer advice on how to restore order.

On 26 November 1811 an official notice signed by the town clerk was posted around Nottingham:

" The Magistrates have observed with extreme regret, that the Spirit of Disorder which has for some time past disgraced the County in the immediate neighbourhood has at length found means to proceed to the Destruction of Frames within the Town of Nottingham: I am therefore directed to give Notice That for the maintenance of the Public Peace in order to enable them to give immediate protection to the property of their fellow tradesmen, the magistrates have taken effectual means by which an adequate Civil and military Force can be assembled and brought to the immediate Assistance of any Person or Persons in the Town whose person or property may be in danger. And in order that every individual may know as well by night as by day where to apply for aid I am further desired to state for the information of the public that a number of Constables will be kept in constant attendance at the Police Office to give immediate information to the magistrates so long as they consider such precautions necessary."

This claim brought an ‘Address from the Framework Knitters to the Gentlemen Hosiers of the Town of Nottingham’, published in the Nottingham Review on 29 November 1811 pointing to the economic conditions under which the knitters laboured, and the need for better regulation of the trade, but it did not stop the frame breaking. On 27 November a frame was broken at Carlton, and a number of frames being moved to Nottingham were attacked at Redhill. The following day four frames were broken at Basford and three to five at Bobbers Mill. Between 31 and 37 frames were broken at Beeston, Blidworth, Basford, Radford and Bobbers Mill on 29 and 30 November.

To counter the apparent threat to public order special constables were sworn in for every village affected by the disorder. They were to patrol nightly. A curfew was also imposed: ‘no one is to be found out of his house after 10 o’clock under pain of arrest and any meeting of persons to be instantly dispersed by the civil or military power’. Publicans were ordered to close their houses at 10 p.m. A notice circulated around Nottingham on 2 December and posted on church doors and other public places, warned that ‘all persons seen out of their houses after ten o’clock at night will be apprehended by the constables and kept in safe conduct until they can be taken before a magistrate’.

On 4 December 1811 negotiations commenced between delegates representing the knitters and the hosiers. These continued through December and the intensity of the incidents declined. The town clerk of Nottingham put this down to better organisation on the part of the authorities: ‘the good effects of these precautions have been strongly evinced by their consequences’. Fewer than ten frames had been broken in the town, and two men were arrested by constables on evening patrol. On another occasion, constables caught frame breakers at work and only failed to arrest them when they ‘escaped out of a two pair of stair window at the back of the house’.

George Coldham, Nottingham’s town clerk reported that ‘I am sorry to say that these proceedings of the people have produced considerable alarm among their Employers and daily dispose individuals amongst them more or less to conform their modes of conducting their business to the will of the people’. He was not alone in adopting such a position. On 15 December the Prince Regent issued a proclamation offering a reward of £50 to any party instrumental in the conviction of a frame breaker, and notices to this effect were quickly distributed through the county.

On 28 December an agreement was signed between the hosiers and the knitters designed to ensure that average wages would rise. The Duke of Newcastle, the lord lieutenant of the county, hoped this would be the end of the unrest.

Unfortunately some Nottingham knitters remained dissatisfied and some hosiers refused to be bound by the terms of the agreement. As a result, the New Year saw more frames being broken in the villages around Nottingham: one in Wollaton on 2 January, 9 in Basford and 2 in Bulwell on 3 January, 7 in Hucknall, and two lace frames in Nottingham on 4 January, 2 more lace frames in Nottingham, and two frames in Basford on 5 January, and 13 frames in Radford and 5 in Arnold on 6 January.

In addition, ‘a great number of men armed with pistols, hammers and clubs, entered the dwelling house of George Ball, framework knitter of Lenton, disguised with masks and handkerchiefs over their faces’. They struck and abused Ball, and ‘wantonly and feloniously broke and destroyed five stocking frames standing in the work shop, four of which belonged to George Ball, and one frame, 40 gauge, belonging to Mr Francis Braithwaite, hosier, Nottingham’. A reward of up to £200 was offered for a conviction.

It was clear to those in authority that the Luddites were increasingly well organised. Coldham admitted as much when he wrote to the Home Office on 14 January 1812: ‘they have lately exercised great judgement and discretion in the selection of their victims in the town by fixing upon the property of individuals on some account obnoxious to popular resentment. The last frames destroyed in the town belong to persons who have been in the habit of paying the workman in part or in whole in goods generally inadequate in value to the price of his labour.... they feel a confidence which is hardly ever abused in each other and refuse to trust any person not concerned in the trade.’

The hosiers refused to agree to further concessions, partly because the number of troops stationed locally gave them some hope of holding out against the claims of the knitters, who in turn were unable to enforce the general agreement reached on 28 December. Meantime the disturbances had spread to Derbyshire and Leicestershire, and into the West Riding of Yorkshire. In February 1812 the Home Office brought in legislation to render frame breaking a capital offence. It was during the debates over this bill in the Commons and Lords, that Lord Byron made his maiden speech in the upper house. The bill became law on 1 March 1812. Its terms and conditions were to last for two years in the first instance.

Tension ran high in Nottingham as the Assizes approached, since several Luddites were due to be tried. Coldham insisted that troops needed to be strategically placed in the town because of fears that attempts might be made to free the prisoners by force, and witnesses intimidated; indeed, he believed that ‘persons had actually been dispatched into the Country to murder or remove out of the way one of the leading prosecutors of several of the individuals against the framebreakers’.

The Assizes were held on 17 March. Two of the Luddites were acquitted and the rest sentenced to transportation. The new legislation, with its capital punishment proviso, did not have to be invoked, much to the relief of the town clerk.

The legislation did not prevent Luddite activity, but it did diminish during the summer of 1812. Further outbreaks occurred in November and December 1812, both in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. Apart from an isolated attack in November 1813 at Wymeswold, Luddite activity seems to have been muted until the Spring 1814. As Coldham informed the Home Office in February 1814 ‘the trade of the town is revived to an extent which is truly wonderful. The increase of work and of wages will I should hope take from the workmen all cause of discontent and all occasion for combining to increase their wages.’ However, on 2 April three frames were smashed at Kimberley, and two days later another five at Thomas Morley’s workshop in Greasley. Enquiries failed to find any evidence as to the perpetrators. Twelve warp-frames were broken at Castle Donington on 10 April, and the following day 5 silk-frames were broken in Nottingham. George Bateman reported that three or four men entered his house at about 9 p.m., went upstairs to his workshop, and began to break his machines. When Bateman’s wife raised the alarm, the men left ‘having considerably damaged 5 frames therein’. The magistrates, having been alerted to the attack, summoned constables ‘to patrol the town in every direction during the night’. Coldham wondered whether this new phase was a result of the expiry of the 1812 legislation, but he soon found that economic conditions had improved to the point where activity slowed down or even stopped.

Further outbreaks of machine breaking took place in October 1814, March 1815, and June 1816 but they were not on the scale of the earlier activities, and the movement had shifted away from Nottinghamshire towards Leicestershire (particularly Loughborough) and Lancashire, Cheshire and Yorkshire.

Occasional outbreaks were now countered with a strong response. On 18 March 1817 Daniel Diggle, 21, was brought before Mr Baron Richards, at County Hall, Nottingham (then on High Pavement), charged with attempting to shoot Mr George Kerrey of Radford. On 22 December 1816, Diggle, with William Burton and two other men named Henfrey and Wolley, had gone on a framebreaking expedition to the house of Mr Kerrey who resisted. Diggle fired at pistol at him. Kerrey was not seriously injured, but Diggle thought he had killed him ‘and with his confederates made a precipitate retreat’. Diggle was subsequently arrested when caught poaching near Trowell, and when one of his co-poachers turned King’s evidence Diggle was convicted of shooting at Kerrey. Diggle was executed outside the county gaol on 2 April 1817. His dramatic ‘authentic confession’ was printed and distributed at the time of his hanging.

As the result of this incident, and a number of other successful prosecutions in Loughborough and elsewhere, Luddism gradually faded away. At its most simple level Luddism was about the defence of hand trades in the textile industries in the face of innovation which threatened jobs and with it livelihoods. It applied across a wide range of interests including threshing machines in the Captain Swing riots of 1830-2, and handloom weaving in the Lancashire cotton trades.

Was Luddism simply an economic movement, or was there more to it than this? Many commentators, both at the time and subsequently, have taken the view that although it probably began primarily as a reaction to economic conditions, it became politicised and organised, a common conception when covert tactics and a fictitious leadership name were used. The secrecy of the movement, and the nature of its activities, meant rumours abounded. According to a contemporary, William Felkin, there were said to have been four companies or gangs, one each for the districts of Sutton Ashfield, Nottingham, Arnold, and Swanwick.... They made their attacks in parties of from six to fifty, and seem to have implicitly obeyed the command of their leaders. Those on guard were armed with swords, pistols, guns, and other weapons; the actual frame breakers carried sledge hammers, axes &c. After the work of destruction was done, the captain called them over by numbers, to which they answered and on his firing a pistol the men uncovered their faces and dispersed.

This sense of order and organisation among the machine breakers was heightened by the use of the threatening letter. This enabled working people to present demands in a way that protected individuals from possible employer retaliatory action had they known the identity of those involved. In the Luddite troubles, the threatening letter suggested that an organised movement existed potentially able to rally significant numbers with which to oppose the forces, such as they were, of law and order. Since the authorities found it problematic, even with significant ‘rewards’ on offer, to identify any Luddites, let alone their leaders, at least before 1816-17, and since the Luddites were apparently able to strike at will and more or less unopposed, a sense of alarm gripped both local and central government through the Luddite years which probably meant that the precautions taken were far more draconian than the actions could ever have justified.

The Luddites produced many documents, including letters, proclamations, poems and songs. They included petitions seeking support from the authorities for the regulation of trade, and economic analysis asserting the rights of labour. Some were political, proposing radical and in some senses revolutionary politics. Taken together they were a uniting force for all the different strands of Luddism, holding everything together through the over-riding message, which was General Ludd’s assertion and defence of a traditional way of working. As such, anyone who was opposed to government, whether defending the economic order, or advocating a new political order, could call upon Ludd in support of their viewpoint. This has led some historians to conclude that Luddism may have begun as an economic force, but that it turned into a revolutionary movement nipped in the bud partly by government action, and partly by the return of inertia when economic conditions improved. At the same time, the general thrust meant that Luddism could flourish in different contexts between the east midlands, Lancashire and Yorkshire, despite the absence of a common agenda.

Blackner referred to the first round of frame breaking in March 1811 as resulting from ‘their mutual sufferings’, and William Felkin agreed that it had started because ‘the times became troublesome and dangerous, issuing in the revival of Luddism’. But there is little doubt that the reaction of the state, particularly the town clerk of Nottingham and the Home Office, suggested a real concern that Luddites had an underlying political message, which might be a prelude to insurrectionary activity. In this atmosphere, radicals and some determined groups of revolutionaries who had been active since the 1790s, sought to divert the movement into a stronger sense of political and not just industrial grievances.

The Nottingham Gazette accused the Nottingham Review, which was founded in 1808 as a radical paper as distinct from the Tory Nottingham Journal, of being an advocate and apologist for the Luddites. In May 1814 the Gazette concluded that Luddite violence could be attributed in part to the machinations of ‘pretended patriots' - the political opposition - who used the depression in the trade for political objectives, and it clearly associated these with the politics of the Review. It interpreted Luddism as essentially a revolutionary protest.

An example of a Luddite poem written at the height of Luddite activity in Nottinghamshire: ‘Mr Perceval’ (Spencer Perceval), who is referred to in the first verse, was the Prime Minister who was assassinated in May 1812. His administration had introduced the Framework knitters bill into Parliament in February 1812 that proposed the death penalty. Byron’s maiden speech opposed the bill, speaking of ‘men meagre with famine, sullen with despair ... will you erect a gibbet in every field and hang-up men like scarecrows?’

Well d(o)n(e) Ned Ludd, your cause is good,

Mr Perceval your aim,

By the late bill ‘tis understood,

‘Tis death to break a frame.

With dextr(ou)s skill the Hosiers kill,

For they are quite as bad,

To died you must by the late bill,

Go on my bonny lad.

You may as well be hanged for death,

As br(ea)k(i)ng a machine,

So now my lad, your sword unsheathe,

And make it sharp and keen.

We’re ready now your cause to join,

Whenever you may call,

To make foul blood run fair and fine,

Of tyrants gr(ea)t and small.

P.S. Deface this who dare

Shall have tyrants fare,

For Ned’s everywhere,

To both see and hear.

An enemie of Tyrants