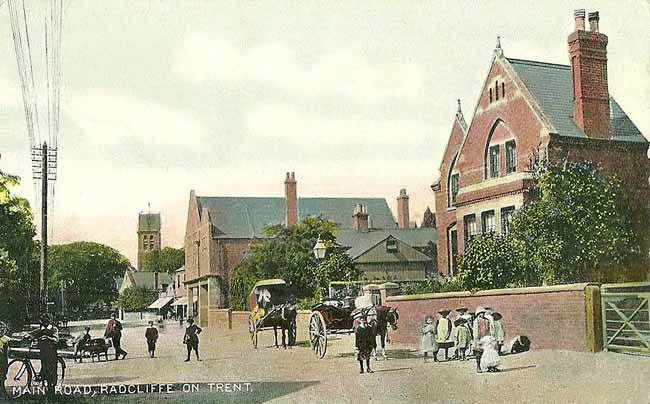

Main Road, Radcliffe-on-Trent, c.1910.

Main Road, Radcliffe-on-Trent, c.1910.The village of Radcliffe on Trent lies five miles south-east of Nottingham on the south bank of the River Trent.

What attracted the early settlers?

Its site borders the River Trent, which provided a water supply, food through fishing and a transport route. While the lower ground to the west floods, it does offer rich pastureland. The drier higher ground to the north and east is suitable for arable farming and the building of dwellings.

The village boundaries

Radcliffe-on-Trent on the Ordnance Survey 1 inch to the mile map of 1889 showing the parish boundary.

Radcliffe-on-Trent on the Ordnance Survey 1 inch to the mile map of 1889 showing the parish boundary.The boundaries were fixed many hundreds of years ago and are essentially the same now as they were in the Middle Ages. In tracing the boundary, let’s start at the point which gives its name to the village: the red cliffs on the Trent by the present-day weir.

The boundary with Shelford parish leads southwards in a series of dog legs, at the eastern edge of the large medieval open field named ‘Cliff Field’, which stretched from the river to what is now the A52. These dog legs lead to a short stretch of Oatfield Lane, part of the ancient route from Cropwell Butler to the Trent at Shelford.

Just before reaching the road to Bingham, it crosses the Syke Drain: the stream, now mainly culverted, that ran down the main street to the Trent. Here the boundary, and that ancient route, continue as Henson Lane, with to its west the Breck open field. The name ‘Breck’ indicates that this field, the furthest from the settlement, was sometimes cultivated and sometimes not, depending on how much pressure there was on the land.

The nature of the land itself is reflected by some of the old names of its furlongs, such as ‘Hunger Hills’, ‘Foul Syke’ and ‘Windy Arse Furlong’.

On the far edge of modern Upper Saxondale, the boundary turns west and follows the stream, variously called ‘Radcliffe Dyke’ or ‘Cropwell Dyke’, down its valley past the ‘Breck’, ‘Stoney’ and ‘Sunpit’ open fields into Lamcote. Then the dyke and boundary turn northward to meander to the Trent. Reaching the river, the modern boundary follows the Trent downstream back to our starting point at the cliffs.

However, until 1934, part of Radcliffe parish lay north of the Trent, an area named ‘Hesgang’. ‘Hesgang’ means ‘horse pasture’, its early use. This is the area of the modern ‘Netherfield Lagoons’ nature reserve. Clearly, the curve of that former boundary marked an ancient major course of the Trent.

Another complication is that, until modern times, Lamcote was in the ecclesiastical parish of Holme Pierrepont, but in the secular administrative one of Radcliffe.

Early history

While the first reference to a place called Radcliffe was almost 1000 years ago in 1086, there certainly was a human presence in this area, hundreds of years before then.

Stone Age tools have been found within the parish, south of the A52 and on Clumber Drive; a Bronze or Iron Age boat was found on the border between Radcliffe and Holme Pierrepont and there were Iron Age dwellings at Gamston.

Later were Roman villas at Newton and Bingham, the Roman fort and settlement at Margidunum and the major Roman road of the Fosse, less than a kilometer from Radcliffe’s parish boundary.

Recently discovered was a Romano-British farm at the top of Shelford Road; there were Anglo Saxon cemeteries at Cotgrave and Holme Pierrepont.

Domesday

In common with most settlements, the first reference to Radcliffe is in the Domesday Book, which tells us that in the second half of the 11th century:

- There were two manors or estates in Radcliffe and three in Lamcote.

- The identities of the landowners before and after the Norman Conquest,

- A description of the land and

- The size and makeup of the population, because the villeins and bordars (the two classes of serf) were assets belonging to the landlord.

The landowners before the Conquest were members of the Saxon elite. They were absentee landlords, with many other manors and their bases away from Radcliffe. Thus, they cannot be counted among the first residents.

They were replaced by the new Lords of the Manor:

- Healfdene of Cromwell, who was unusually a Saxon tenant in chief of 12 manors, an ancestor of both Thomas and Oliver Cromwell.

- Ralph de Buron who was based in Horsley, Derbyshire.

- Roger de Busli of Tickhill Castle in Yorkshire.

- Walter de Aincourt, after whom our Dayncourt School was named.

- William Peverel the illegitimate son of William the Conqueror, of Nottingham castle.

The last four were all rewarded for fighting at the Battle of Hastings.

All were tenants in chief of the King of double or three figure numbers of estates, and so what they have in common again is that they were absentee landlords, for whom Radcliffe would be just a minor item in their portfolio of estates.

Domesday population

The Domesday Book tells us that living in Radcliffe were 40 adult males (2 sub-tenants and the serfs: 29 villeins and 9 bordars). Lamcote had just 4 adult males (2 sub-tenants and 2 villeins). The approximate population can be estimated by multiplying the total of 44 adult males by 5, giving a total for the two settlements of 220.

We also learn that the area contained arable and pastureland and a fishery.

In 1289 Richard de Burton gave to Thomas Bayseley ‘certain villeins, lands and houses in Radcliffe’.

What more do we know about the medieval village?

Open field system

The agricultural land of the village was farmed in five large open fields, divided into hundreds of strips grouped into furlongs. A tenant farmer’s strips would be scattered around the open fields and farmed communally under rules agreed at the manor court.

There was also pastureland, with regulated grazing rights, and waste land.

Residential core of the village

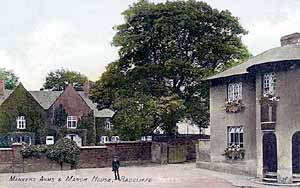

The Manor House and The Manvers Arms, c.1910.

The Manor House and The Manvers Arms, c.1910.Even without the benefits of a detailed map until 1710, we can say confidently that the layout of the village would follow the East Midlands pattern of open fields and a nucleated village, that is one with concentrated not dispersed dwellings.

Dwellings couldn’t be built in the open fields, so the early settlement would be in the core of the village by the church, probably with the basic street pattern that we see centuries later.

Self-sufficiency

Despite the proximity to Nottingham with its market, Radcliffe, like other villages, needed to be self-sufficient.

Most people worked on the land to provide food, both for their own needs and for the surplus taken by the lord of the manor and the church, but other trades and crafts were needed. There would have been carpenters, tailors, shoemakers, millers, smiths, brewers, and bakers.

There is a steady increase in population, interrupted most dramatically by the devastation of the Black Death, which arrived in England in 1348. There is no reason to believe that Radcliffe escaped this disaster.

There is a steady increase in population, interrupted most dramatically by the devastation of the Black Death, which arrived in England in 1348. There is no reason to believe that Radcliffe escaped this disaster.

The dramatic loss of life from the Black Death and the reduction in the labour force led to an abandonment of marginal land and a collapse of the manorial system.

In general, there was a consolidation of land ownership by absentee major landowners and, to a lesser extent, by the village elite. At the start of the 18th century two of these major landowners were the Rosell family from Cotgrave, and the Duke of Kingston, one of whose homes was Holme Pierrepont Hall.

Occupations

We don’t have occupations from censuses for another 140 years but, most unusually, the Bishop’s Transcripts (the copies of the parish registers that were sent to the bishop) for a four-year period from 1716 state the occupations of the heads of household.

As you would expect, this paints a picture of a rural, overwhelmingly agricultural, economy.

The Manvers estate

The Rosell estate map of 1710 looks to have been drawn up in preparation for the estate being put up for sale and, indeed, it was bought in 1722 by the Musters of Colwick, who, two years later, sold it on to the Manvers estate.

The Manvers had been lords of the manor of Holme Pierrepont since the 1200s and had, since then, advanced in status from Baron to Earl and, in 1715, to Duke of Kingston upon Hull.

This purchase doubled the Manvers properties in Radcliffe, adding to their already extensive land holdings, not only in Nottinghamshire (where their main seat was at Thoresby Hall) but in Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, Norfolk, Shropshire, and Wiltshire. They already owned much of Lamcote.

The Estate was steadily extending its holdings in the village. In 1732 the estate owned 49% of the land but by 1746 this had risen to 60%. It didn’t farm this land itself but let it out to tenant farmers.

Enclosure

Radcliffe’s Enclosure Act of 1790 broke the open fields into hedged discrete fields. These fields were individually owned, albeit in the main by the Manvers family, and so could over the years be developed for housing and other non-farming uses.

This process extended control over the village by the Manvers family.

Transport

Radcliffe was not isolated. Its position on the Trent meant that, when transport was much easier by water than land, residents would have seen the passage of many craft, from Viking longboats to trading vessels.

There was an active wharf from at least 1779, with wharfingers and boatmen employed, and a ferry operating until the late 1930s.

Radcliffe-on-Trent station, c.1910.

Radcliffe-on-Trent station, c.1910.But something far more important for the future of Radcliffe occurred in 1850, with the arrival of the railway. The period of its actual construction must have been dramatic. This local stretch of the ‘Nottingham to Grantham’ line was, itself, a major construction project. The laying of miles of rail track from the north bank of the Trent at Colwick to Saxondale involved building a bridge over the Trent, a viaduct over the flood plain and then a cutting through the village itself.

All this was constructed between February 1848 and July 1850 by a labour force of 300 navies, housed here. This must have been eventful enough, but more important in the long term were the consequences of its arrival.

This first 1850 timetable shows that:

- there were 4 trains a day in each direction,

- it took 15 minutes to travel from Radcliffe to Nottingham and

- there were four classes of comfort, or discomfort, at four prices.

The dramatically reduced journey time meant that it became feasible and attractive to work in Nottingham and live in Radcliffe, and affordable, if you happened to be a factory owner or a professional.

The cheapest return fare from Radcliffe to Nottingham was 10 pence halfpenny: a considerable sum for an agricultural labourer earning just 10 shillings a week. It should be said, however, that fares did become relatively cheaper, so that clerical workers, for example, were able to commute.

Radcliffe’s Trent-side location attracted hundreds of day trippers. It is recorded that on Whit Monday 1881, 2000 visitors descended on the village, more than doubling its population of just 1,700.

Again, there was a significant increase in Radcliffe’s population over the next 50 years. By the fourth quarter of the 19th century Radcliffe was no longer a purely agricultural village.

From the 1860s, fields within easy reach of the station were sold off for housing, especially in the building boom of the 1870s. New dwellings were built for more affluent residents, such as those on Lorne Grove: housing was spreading out from the historical core of the village.

But it wasn’t only businessmen and professionals who needed to be housed. There were also dwellings being built for workers and their families, often meaner houses of poor-quality construction that, unlike the middle-class houses which still survive, have disappeared. These were on Bailey Lane, Back (now Water) Lane and the yards squeezed into the Mount Pleasant and Main Road areas. These overcrowded areas of Radcliffe were notoriously unhealthy and were the subject of articles and correspondence in the Nottingham newspapers. The cholera outbreak of 1849, with Mount Pleasant at its centre, was followed in 1859 by smallpox, and in 1881 by scarlet fever epidemics.

The Manvers estate had been selling off land, piecemeal, for building since the last quarter of the nineteenth century. This pattern accelerated. In 1897 the 130 acres of Lings Farm were sold to the County Council for the building of an asylum, where Upper Saxondale now stands.

In 1919 Bingham Rural District Council bought 21 acres off Shelford Road for housing: ‘homes fit for heroes’. The biggest sale of Manvers land took place on 3rd March 1920, when many properties and land were sold.

The population increased steadily in the first half of the 20th century. Noteworthy is the impact of the opening of the Asylum early in the century. The 1920 Manvers sale and the last one in 1940, finally ended the Manvers presence in the village. These sales made possible the spread of housing, outwards from the village core.

But it has been the years since the Second World War that have seen the most dramatic changes in Radcliffe.

This shows the significant increase in population, accompanied by an increase in dwellings and the continuing spread of the built area from the old village core.

Centre of the village

Matching the outward spread of homes have been substantial changes in the village centre itself. Main Road has changed from being a street of residential homes, pubs and a few shops, to the retail centre for residents, not only of Radcliffe, but of neighbouring villages.

Looking back

The size of population has increased steadily from an estimated 240 in 1086 to 8222 in 2018 and of dwellings from 44 to 3570.

Where there were fields in 1800 there are houses, with the built area spreading out far in all directions from the historic core.

It’s certainly true that the residents of 1086 wouldn’t recognise modern Radcliffe. What we can confidently conclude is that, over the ages, people have wanted to live in Radcliffe and continue to do so.

Further information on the history of Radcliffe on Trent can be found at

radcliffe-on-trent-local-history-society.co.uk/