Evacuees leaving from Nottingham Midland Station in September 1939.

Small children stand, well scrubbed, tightly buttoned up in their best clothes, suitcases in hand, gasmasks strapped across their chests and large luggage labels pinned to their coats while anxious mothers fight back tears and smile encouragingly. This is most people’s abiding vision of the mass evacuation of children in September 1939. However, not all the eligible children were evacuated, and in the first wave from Nottingham only 20% of the expected 22,000 children and their teachers presented themselves at the appointed time and place.

Although initially Nottingham was not expected to be one of the cities to be bombed by the Germans, as soon as war broke out, strong representation by the Ministry of Health and the fact that there were so many offers of homes for evacuees resulted in Nottingham being added to the preparation list in July 1939. So what happened to change the lives of so many families in Nottinghamshire over 1939-1945? Some children had fun, others suffered at the hands of unscrupulous hosts, and others either returned home or were re-evacuated as circumstances of the war changed. For many, the changes were profound.

Even before war was declared, the rather darkly named 'Operation Pied Piper' set out preparations to evacuate school children, children under five with their mothers, pregnant women near their time, blind people and those with a disability which would made them unable to access air raid shelters. In July 1939, families were sent letters offering them the chance of evacuation if they qualified. When war with Germany was finally declared in September 1939, two problems faced the organisers. Schools which were to be the coordinating centres were closed by government order and the Regional Commissioner imposed restrictions on the numbers of children who could assemble at any one point so the evacuation had to be done in stages. The Evacuation Officer in charge of putting the plans into action in Nottingham was the City Treasurer, Mr Jesse Boydell.

Teachers called at the homes of those who were eligible for evacuation and gave them the time and place to present themselves. Special buses and trains were laid on and school children were sent in parties of 10 accompanied by their teachers. Because of the new rules, the children were collected every quarter of an hour at each school. They were allowed to take as much luggage as they could carry, and parents were expected to give them food for two meals, although lemonade and other liquids were not allowed. Pocket money for the journey was limited to 2/-. Once they arrived at the receiving centres, the children were given a medical examination and then their emergency rations in carrier bags which included such items as tinned milk, beef, biscuits and chocolate. Volunteers then ferried them by motor car to their destinations. Mothers with children under five did not depart from schools and so buses were provided for them both in the Market Square and at Huntingdon Street Bus Station in Nottingham. On arrival at their destination, the mothers were allowed to send postcards to their husbands free of charge.

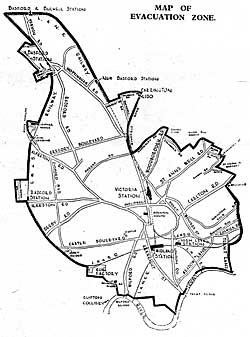

Map of the 'evacuation zone' in Nottingham.

There were three national waves of evacuation. The first was in September 1939 when many children from Nottingham city were sent away from areas including the Meadows, Radford, Basford, Carrington, St Ann’s, Sneinton and Colwick (see map of evacuation zone). In September 1939, of course, many evacuees were received into the Nottinghamshire area away from the city. However, as there was no immediate bombing, many children returned home by April 1940, in the period often called the Phoney War. The other two waves which were produced by fears of invasion on the south coast mostly concerned children being evacuated into Nottinghamshire. Nottingham itself was actually bombed eleven times, most notably once at the end of August 1940 in Mapperley and Sherwood in which a baby was recorded to have been killed on Hood Street. The most destructive raid on the city, however, was on May 8/9th 1941, when 159 people were recorded as having been killed and numerous buildings were destroyed.

The Nottingham Evening Post reported that although the initial evacuation went well, the fact that fewer children than expected had left the city created a shortage of school teachers, many of whom had departed with the evacuees. Schools could not reopen unless they had air raid shelters in place, and there were no immediate plans in place to build them in the city schools as they were expected to be empty and so the long summer holiday dragged on, good for the children but not so for their parents. Complaints were made about children running amok in the city and also of those evacuated causing chaos in the countryside, unable to settle to country ways. There was pressure put on parents in the city to let their children go, but many still resisted, wanting to have their children close. The official line taken for the disappointing evacuee figures placed the responsibility squarely on the shoulders of 'selfish and ungrateful parents'. Many had not wanted their children to go because they did not know where they were being sent. There was also a rumour that it was only unwanted children that were being sent away. On September 13th, the Nottingham Evening Post reported that, "the whole difficulty (of the education authority not having the facility for educating those not evacuated) has arisen through parents' non-acquiescence to what unquestionably was a very fine scheme for the benefit of their offspring."

Evacuees from Sheffield arrive in Bingham.

As well as children being evacuated from the city, in September 1939 villages in Nottinghamshire were preparing to receive the evacuees from both Nottingham and other cities such as Hull, Leeds and Sheffield. Receiving towns and villages included Kimberley, Ruddington, Bunny, Costock, Trowell, Papplewick and Gotham. Although the scheme was voluntary, those offering billets received around 10/6 per child, and parents were expected to contribute to this, although about one quarter of these were exempt because of means testing and so did not have to pay anything. Parents were also expected to provide their children’s clothes and shoes but this was not always practical because of children growing and perhaps needing different clothes in the countryside. Many foster families and voluntary services in the villages helped out with 'hand me downs' and 'make and mend' parties, and teachers held weekly inspections to see which children needed new clothes or shoes. However, there were some unscrupulous people who took in children and 'forgot' to tell the billeting officers when they had returned home, continuing to claim money for them, and some who crowded a number of children together in order to receive the maximum amount of money for them. Children were expected to help out with chores and were not always paid for this.

At the beginning of September 1939 some 23,000 women and children were received across the county of Nottinghamshire, and the system was put into place like clockwork. One example from the Basford area shows how 169 schools were used as evacuation reception centres for evacuees who had arrived by 40 trains and various buses. The railway station at Ruddington was reported to be handling 700 evacuees per train. In Mansfield, the Miners’ Welfare Convalescent Home at Berry Hill took in 300 expectant mothers and children under five. However, on 2nd September officials at Southwell reported that "anticipated numbers were not arriving: 4,445 had arrived the previous day but of similar numbers expected today, only 47 arrived on two trains."

The SS Volendam.

Some parents evacuated their children abroad if they had family or friends who would take them and this was organised through the Evacuation Committee. From Nottingham, two children successfully went, one to South Africa and another to Canada. However, Joan Gilder of Radford was on her way to Canada on the SS Volendam when it was torpedoed. She survived and it was reported in the Nottingham Evening Post that "she was none the worse for her experience". One must remember that there was no National Health Service or psychological support available for traumatised youngsters such as this one. 'Keep Calm and Carry On' was the order of the day. Nevertheless, the overseas evacuation programme was abandoned shortly after this when the SS City of Benares was torpedoed and 77 of the 90 children being evacuated were killed.

Much is made of the stories of the evacuees, but what about those left behind? How were the men going to manage if their wives had gone? In Hartford Road, three men in adjoining houses were left without their wives and children. The mother in law of one volunteered to cook for all three. One of the lucky men commented, "She’s a really good sort and we are certainly glad for the help." Another husband told the Post, "it’s a hard blow losing them, but they will be better off. When the siren went the other night my wife was so excited that I realised that if she had been on her own she would never have got the two children’s gas masks on, let alone dress them and get them to a shelter. I feel much easier in my mind now. Where she is going she will have the help of others should the need arise." This was reported in September 1939, so one must assume that there had been air raid practices beforehand where the hapless wife had panicked.

The Nottinghamshire County Council Board of Education minutes of July 1940 (Nottinghamshire Archives Office: CC 4/10/4/17) recorded that some evacuated children were writing home to their parents with exaggerated rumours of the war. They give the example of a letter from a child billeted in Cornwall writing that a great number of parachutists had descended on a neighbouring village, "There were only 30 men to defend the village and over 200 parachutists – now we are afraid of going out." In fact, no parachutists had been in evidence at all. Teachers were recommended to check such rumours first with the Ministry of Information as a "great service to public morale."

As children were evacuated with their teachers, their education carried on, often on a part time basis to begin with until things were settled. During the school holidays volunteer teachers set up activities for the children to ease the burden on the foster parents. Other problems beset the education of children, as school buildings were sometimes requisitioned for war purposes. In January 1940, only 19 of the 120 schools in Nottingham were fully open and a shift system became operational with some children being taught in the mornings, others in the afternoons. Teachers were in short supply as many had gone with the children who had been evacuated, based on the expected numbers, which as we have seen, were lower than expected. Other teachers had been called up for military service. As well as lessons, children took part in the many wartime activities, such as growing crops, the Dig for Victory campaign, keeping chickens in the school yard and waste paper collections, as well as the air raid practices and gas mask drills. Nuthall Road and Perry Road playing fields and the school field at Jesse Boot school were ploughed up and used as allotments.

Small study circles met up in village halls and public libraries and many children benefitted from these small groups and made good progress. School trips were also organised to local factories and collieries and to Wollaton Hall. By March 1940 most schools were back in use for their original purpose, although some had to rely on retired teachers. Nottingham Boys High School called in two over 60's to run their cricket team, but it was reported that the team still gained excellent results.

Some evacuees needed to be kept together for their schooling, such as 32 blind pupils from different areas who were billeted together at Normanton Hall, Southwell. Others such as a group of Roman Catholic children who came from Leeds caused the Evacuating Committee a few headaches in trying to keep them together, but problems were usually sorted out with the help of willing volunteers. One such centre was set up in Burton Joyce where the billeting officer, Lady Readett-Bailey, furnished and equipped an empty house for 'difficult' boys. It was reported in the minutes of the Education Committee on 31 July 1940 that the boys had become better disciplined and that they had increased in height and weight in every case since their arrival.

School log books give interesting information on activities to keep the children occupied. In October 1940 Cropwell Bishop School "received wool and 15 girls commenced knitting helmets, gloves, mittens, socks and scarves for the Nottinghamshire Services Comfort Fund" whilst the older children engaged in potato picking. The boys in Brinsley School were luckier. In May 1941 "Mr Pierce, Air Raid Warden brought a Spitfire Engine into the school grounds on a lorry for the boys to examine." Out of school hours, many children had nothing to do and the authorities were worried about delinquency but did not want to go down the 'Hitler Youth' road, so youth clubs were opened and children were encouraged to attend these or join the scouts or guides, but these were not terribly popular. Truancy was also a problem. One headteacher wrote in his school’s logbook in August 1942, "this afternoon 5 boys were not present, 3 subsequently came back; probably a case of truancy. (The attraction was an overturned trailer laden with biscuits)." In October 1939, the head teacher of Newstead School wrote, "A few more children have returned to Nottingham and at this rate I am afraid that in the course of a few weeks the scheme will have to be regarded as a failure." By May 1944 this school only had one evacuee on their roll.

Schools were not supposed to open until they had air raid shelters, although those without could have schemes called 'scattering' where children would either be taken to safe parts of the school or scattered to houses within a five minute walk from the school. One evacuee, speaking later, told that in order to decide which children went home, they were told to run home as fast as they could and those who did not make it in five minutes would be kept in school in an air raid. These were practised in the same way as air raid shelter practices. Those schools with shelters had to prioritise children between the hours of 8.30 and 5.00; otherwise other members of the public could use them. Henry Mellish School had a shelter to accommodate 500 people whereas that of Bramcote School had a capacity of 75. Bluecoat school pupils dug 20 feet into the sandstone under their school for a cave air raid shelter that was capable of holding 100 people.

Schools had to cater for incoming evacuees and some teachers found the children less amenable than their 'own' children. The Hoveringham School logbook records, "the evacuees are a very noisy crowd, knowing, or showing no obedience." Host mothers were shocked at the manners and health of some of the inner city children who came to stay, many of them malnourished and smaller than rural children of the same age, turning their noses up at healthy food and asking for fish and chips instead. Many had head and body lice. The annual report of the County Schools Medical Officer, Dr Christopher Tibbitts, reported in 1940 that all incoming evacuees were medically examined and more than a quarter had signs of 'verminous infestation' and a number also had skin diseases. In September1939, a woman in Bottesford was badly upset that the beds in her home "had been made alive by Sheffield children." The local authority was liable for paying compensation to householders whose furniture or bedding was damaged by evacuees.

However, some children settled well with their host families and remained in touch after the war. Thurgarton took in evacuees from Sheffield in September 1939, and only seven remained after the Phoney War. However, with the threat on invasion on the south coast in 1940, 18 children and one teacher came from Southend increasing the school roll to 43 pupils compared to the roll of 30 in 1937.

For some, it was an idyllic life: Gladys Topmans came as a seven year old with her younger sister who was four, and they stayed until 1944, enjoying the village atmosphere. Others, such as Ken Lambert and his brother Peter saw evacuation as an adventure and got into a number of scrapes, some ending with the cane. The boys were taken home by their parents in summer 1943, although they had not wanted to leave. There were reports of evacuee children never having slept on beds before and jumping up and down on them with pleasure.

So, was the evacuation of children and other vulnerable members of society successful? Yes, in many ways. The first phase was very well organised although the take up was poor and some children returned home during the first few months when the expected bombing of cities did not materialise. When raids started, people were keen to evacuate their children and it certainly saved many lives. It gave some city children the opportunity to live in a different environment with better food and conditions than they had been used to. Their education became more informal as they learnt about farming and worked together for the war effort as well as their ordinary lessons. Some friendships were made for life. It is also claimed that people became more aware of the poor health of many city dwellers and this went some way in paving the way for the National Health Service after the war. Financially it was a heavy burden on the taxpayer, but in the greater scheme of things, the cost was subsumed in the overall costs of the war. Psychologically, some children suffered at the unscrupulous hands of some hosts but overall the benefits of the majority have left a lasting memory of adventure and a sense of self-reliance in their memories.

Further information

Lance Wright's research will be deposited at Nottinghamshire Archives in a folder labelled 'Evacuation 1939-1945 in Nottinghamshire.' Please note that some school data is restricted so researchers should contact Nottinghamshire Archives for advice.

The Evacuees Reunion Association is a non-profit making registered charity that was formed in 1995 "to ensure that the true story of the great evacuation would become better known and preserved for future generations."