Structual

Standing Buildings

Two overlapping categories of building with folklore associations are pubs with folklore-related names, and haunted buildings.

Taking the pubs first, there are numerous hostelries in Nottinghamshire named after Robin Hood, Little John, or one of the other personages associated with his legends. None appear to be particularly old. There are also pubs named after other Nottinghamshire tales. For instance, The Cuckoo Bush at Gotham is named after one of the tales of the Wise Men of Gotham, and the Sir John Cockle Inn, Mansfield derives its name from the ballad The King and the Miller of Mansfield and the stage play version written by Robert Dodsley.

|

Cursed Galleon at Ye Olde Trip to Jerusalem, Nottingham, before and after its exorcism and move. Courtesy of the Evening Post and www.history.uk.com. |

A few pubs’ names relate to seasonal customs. The various Maypoles, for instance, at Hucknall, Wilford and Newark require no explanation. The unique Speed the Plough, Sutton-in-Ashfield, probably derives its name from a traditional toast on Plough Monday, although there is also a folk dance entitled Speed the Plough. No doubt there are further interesting names to be discovered.

Of course, many pubs and inns purport to be haunts of various supernatural goings on, for details of which see the ghost books of David Haslam (1996) or Rupert Matthews (2005).

One example will suffice. The Trip to Jerusalem pub, Nottingham, which claims to be the oldest pub in England, and which is partially carved into Nottingham Castle Rock, has its famous cursed galleon. This model sailing ship used to hang from the roof of one of the upstairs caves. It was said that if anyone moved it or cleaned it, they would die soon after. It therefore remained uncleaned, and acquired a thick unhealthy-looking layer of dust and cobwebs. A few years ago, the pub was refurbished, and it was decided the galleon needed to be moved, but no one was prepared to do the job. A cleric was therefore brought in to exorcise the curse. The galleon now sits in a glass case – still undusted – above the upstairs bar.

The Trip to Jerusalem is also home to an unusual local pub game called ‘Bull’s Horn’. A cow’s horn is mounted on the wall of one of the cave rooms, and a bull’s nose ring is suspended from the ceiling some distance away from it. The aim of the game is to swing the ring so that lands on the horn and stays there. So many people have missed the horn that the ring has carved a groove in the sandstone cave wall all around the room.

Folklore can also be found in the architecture of buildings, particularly in church architecture and furnishings. The carvings in Southwell Minster in particular include a number of so-called “foliate heads” or “green men” – human faces with foliage growing out their mouths to form a surrounding wreath. The significance of these faces has not been settled. Some people, notably New Age Pagans see them as relics of England’s pre-Christian religions, which seems strange in a church setting. However, others say they may be more in the nature of stonemasons’ trade marks. The “green man” appellation for these heads is actually quite recent, having been coined by Lady Raglan in an article in Folk-Lore in 1939. Before then, the name “green men” was used for heraldic wild men dressed in leaves (see Simpson & Roud, 2000, entries for “Foliate head”, p.127 and “Green man”, pp.154-155).

Another place to look in churches is underneath misericords – the fold-up seats found in many choir stalls. These have a wooden block attached to the undersides of the seats so that when the seats are up, the choristers can still rest on them. Many of these blocks were ornately carved, often with humorous or even decidedly irreligious scenes. These sometimes depicted proverbs or jokes – permissible because these carvings were not normally visible to the general congregation. In Nottinghamshire, there is a misericord with a foliate head at Holy Trinity Church, Wysall. Unfortunately, but unsurprisingly, many misericord carvings were defaced by Puritans during the Commonwealth period.

Ruins & earthworks

|

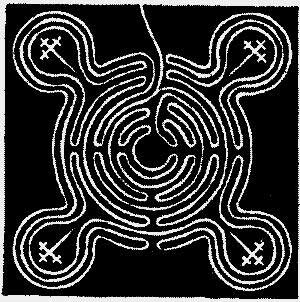

The turf maze near St. Anne's Well, Sneinton, which was ploughed up in 1797 (diameter 51ft.). |

There are legends and ghost stories attached to ruins and earthworks in Nottinghamshire, details of which may be mentioned in relevant local history books. One particular earthwork that deserves mention, if ‘earthwork’ is not too strong a word, is the lost labyrinth or turf maze that used to be situated on Blue Bell Hill near St. Anne’s Well in Nottingham. This was called ‘Robin Hood’s Race’ or the ‘Shepherd’s Race’, and was a winding path cut into the turf. Unlike hedge mazes, which are large-scale path-finding puzzles, the challenge of a turf maze is simply to walk or run the complete path. There is a legend with ‘Robin Hood’s Race’ that it was walked by monks during their meditations, but this may be a Victorian invention. Unfortunately, this maze was dug up at the end of the 18th century, although short-lived copies were made in the 19th century.

At the villages of East Bridgford and Car Colston, and very probably at other locations, people visited the local mounds on Shrove Tuesday to play games. The nature of the games is unclear, but Shrovetide was generally a time for playing a variety of games – for instance mass skipping by the whole community at Hilltop, Eastwood (Bennett, 2000). It was also the time of year when children brought out their whips and tops, hoops, and other toys after the winter.

Archaeological Remains

In her History of Bingham, A. A. Wortley mentions that it used to be the custom for people to visit the Stones on Parson’s Hill on Shrove Tuesday. The stones were a prehistoric henge monument, taken down and broken up on the instructions of the local rector in the 19th century. The remains were buried under an industrial estate car park in 1972. No doubt there are other customs and folklore associated with archaeological remains in Notts.

Landscape

|

The Druid Stone, Blidworth. |

Continuing the above theme, some standing stones have acquired legends regarding their formation, usually involving attempts by the Devil or giants to hurl stones at places that had displeased them. In Nottinghamshire, these stones mostly seem to be natural features with perhaps some shaping by human hand. Familiar examples are the Hemlock Stone at Stapleford, the Druid Stone at Blidworth, and a stone that once stood at Kinoulton. Certain hills have similar legends regarding their formation, for instance the Robin Hood Hills, Annesley, and Hoe Hill between Cropwell Bishop and Cropwell Butler.

The Blidworth Druid Stone has a hole in the middle, through which a child could pass. This may have been one of the holed stones in Britain where mothers would bring their children to pass them through the stone as a protection against rickets, although this requires corroboration with local primary evidence. The adjacent Ricket Lane is encouraging.

There are numerous geographical features in Nottinghamshire that are named after Robin Hood or his associates, not to mention Sherwood Forest itself, his erstwhile stamping ground. These include:

- Robin Hood's Well, near Beauvale Priory (SK495495) – now dilapidated. An alternative name for the old St. Anne’s Well, Nottingham was also Robin Hood’s Well

- Robin Hood's Stable, Papplewick

- Robin Hood Hills, near Annesley (SK515545)

- Robin Hood’s Cave. There are two, one near Annesley (SK515545) and another by the River Maun at Walesby (SK665705)

- Friar Tuck’s Well, Fountain Dale

See Tim Midgley’s website (reference below) for a comprehensive nationwide list of Robin Hood place names.

In some cases, street names such as Maypole Yard, off Clumber Street, Nottingham and Maypole Road, Wellow indicate the sites of certain traditional activities.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the last remaining English open field system at Laxton has its annual Jury Day and Court Leet in the autumn. While the Jury Day and Court Leet are strictly speaking manorial legal institutions for allocating the field strips and settling boundary issues, they have acquired the characteristics and ritual of calendar customs. This is evidenced, for instance, by the token fines of two pence or two pounds for certain misdemeanours. Consequently, they are often included in national lists of English customs.

References

- Frank E. Earp (1991) The Old Stones of Nottinghamshire, Mercian Mysteries, Feb.1991, No.6 [Available online at www.indigogroup.co.uk/edge/Nottston.htm, Accessed 7th July 2007]

- Michael Bennett [ed.] (2002) A Century Remembered: Reminiscences of Everyday Life in eh Eastwood Area. Eastwood: Eastwood Historical Society, 2000, ISBN 0‑9517209‑2‑9, pp.210-211

- Tim Midgley (2006) Places which carry the name Robin

Hood

www.geocities.com/heartland/lane/8771/ robinhoodplaces.html, Accessed 28th Dec.2007 - Lady Raglan (1939) The 'Green Man' in Church Architecture. Folk-Lore, 1939, Vol.50, pp.45-57

- Jacqueline Simpson & Stephen Roud (2000) A Dictionary of English Folklore. Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press, 2000. 2nd ed: Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0-19-860766-3.

- Adelaide A. Wortley (1954) A History of Bingham. Bingham: Bingham Church School, 1954, p.53