Overview

Poverty

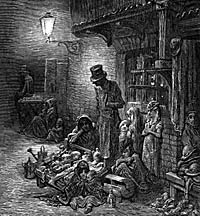

The problem of the poor, and of relieving the poor, goes back many centuries, and in the medieval period was regarded as part of every individual's Christian duty. By the 16th century this was insufficient, and the government began to intervene to help to provide relief for the poor. In 1536 legislation was passed giving individual parishes across the country powers to raise money to provide for the impotent poor – those who were unable to work and so could not look after themselves. In 1576 it passed an Act allowing parishes to set the able bodied poor to work.

The Old Poor Law

In 1601 the Elizabethan poor law statute defined different classes of pauper and suggested that they should receive different types of relief. The impotent poor were to go to poor houses or almshouses, the able bodied were to be set to work in a workhouse and children to be apprenticed. Idle able-bodied people were to be sent to the House of Correction where, as the name implies, they were to be set to work and whipped if they did not conform. Each parish was to appoint an (unpaid) parish overseer to collect a poor rate which was levied on property owners.

From 1662 the overseer was allowed to return anyone who could not show they had the right to reside in a particular parish (usually through birth) to their native parish if they sought relief. Further legislation in 1722 required the able bodied to be relieved only in a workhouse, and parishes were given powers to acquire such premises.

Nottingham Corporation first petitioned Parliament in 1700-01 for permission to build a workhouse, but this project did not materialise until 1726 when all three parishes were leased land by the corporation for workhouses, under the 1722 legislation. The Corporation leased workhouse sites to St Mary's and St Nicholas's for 999 years at 1s yearly. St Peter's completed its workhouse in 1732, but still found it necessary to pay substantial amounts of outdoor relief. In theory the three parishes looked after their own poor separately.

Radford parish workhouse, c.1968 (photograph courtesy of the North East Midlands Photographic Record).

In 1735 the Corporation acquired the land and property belonging to Gregory's Charity. William Gregory a former town clerk, in his will of 1613, gave eleven tenements in Houndsgate to the Corporation for poor people to live in, and 40s (£2) a year to repair them. The Corporation leased the property to the three parishes in September 1732. St Peter's used the land to build a workhouse. In 1788 the Corporation sold the property and divided the money between the three parishes. St Mary's used its share to build twelve rooms in York Street for the elderly, St Nicholas's built eight rooms in Finkle Street, and St Peter's built a new workhouse on the south side of the Broad Marsh on a piece of land left by Margery Doubleday for the purpose of ringing a morning bell at St Peter's Church. The site chosen for the new workhouse obscured Mrs Abigail Gawthern's view over the Meadows from her house on Low Pavement. As a result, ‘Mr Gawthern paid £20 to have the building which was erected for a new workhouse to be taken down, as where it then stood obstructed the view from the Meadows from the back part of our house, and it was removed.'

Elsewhere in Nottinghamshire, by 1776 there were workhouses in Basford, Beeston, Bulwell and Hemshill, Bunney, and Greasley. A workhouse was recorded at Bingham in 1777 with accommodation for up to thirty inmates. Others were at East Retford (up to thirty inmates), Clarborough (sixty) and Sutton (forty). A workhouse was built at Mansfield by 1730, and in the 1770s it was capable of holding fifty-six inmates. Altogether 18 workhouses had been built in Nottinghamshire by 1776.

Gilbert Unions

In 1782 the policy changed. Under the terms of Gilbert’s Act, passed that year, the able bodied were to be found work or subsidised from the poor rate. As a result, existing workhouses became poor houses for elderly and infirm people. Parishes were empowered to come together to form unions to build poor houses. East Retford and twenty-five other parishes formed a Gilbert Union with a poorhouse in 1818 at East Retford. Under the same legislation around 1815 twenty-four parishes formed the Basford incorporation and erected a workhouse for 240 inmates.

Newark built a town workhouse in 1786 but in 1817 it became part of the Claypole Incorporation of twenty parishes, five in Nottinghamshire and fifteen in Lincolnshire with a workhouse at Claypole Bridge in Lincolnshire. The inmates worked on the 60-acre farm and in the one acre kitchen garden. A workhouse was built in Southwell in 1808, which survives, but in 1824 the formation of the Thurgarton Hundred Incorporation led to a union of forty-nine parishes with a new workhouse at Upton, now in the hands of the National Trust after it became the workhouse for the post-1836 Poor Law union.

Workhouses were not necessarily very pleasant places even though under Gilbert’s Act they were mainly to house the poor rather than being punitive. The St Mary’s, Nottingham, workhouse on York Street was described in 1795 as dark, verminous, ill-ventilated, and utterly unable to accommodate the 168 inmates. By 1808 it was in such a poor state that the St Mary's Vestry negotiated with the Corporation for a much larger site on which to build a new workhouse. In the event the Vestry voted to try to save expense by repairing and extending the existing building, which still cost them £5,000. This was not a great success: in 1840 the workhouse was described as ‘very uncomfortable, and not so much like a workhouse as a prison'. St Nicholas's workhouse was declared unfit for habitation in 1813, and the overseers bought a building in Park Row as a replacement.

The working of Gilbert’s Act was generally thought to be favourable to the poor, partly because it encouraged them to stay in the community and find work. Wage subsidization was adopted to help out labourers who could not earn enough to keep their family in food and shelter. It began in rural Nottinghamshire in 1783, twelve years before the so-called Speenhamland system dating from 1795, whereby the parish officers could provide an allowance in aid of wages depending on the size of a family and the price of bread. After 1818 this was gradually replaced by an allowance based only on size of families. Another variant was the roundsman system, where labourers without work were sent around the parish to work, and partly funded from the poor rate. A similar scheme was the was labour rate in which each labourer had a price according to his skills, and employers in the parish took them on at the set rate.

All of these methods were thought to favour the poor too much and to be too costly. Since the annual sums spent on poor relief were increasing, the argument appeared to be incontrovertible, and in 1833 the government set up a Royal Commission on the Poor Law to investigate its working. It reported in favour of a far more repressive regime, which was introduced in the form of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act.

The Poor Law after 1834

Southwell Workhouse. © Copyright Andy Stephenson and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

The 1834 Poor Law was designed with a number of principles in mind. These principles were:

- ‘Less eligibility’ – the lot of inmates to be worse than that of the lowest independent worker outside

- No outdoor relief for the able bodied poor – relief only in the workhouse. In theory, able-bodied individuals who applied for relief were to be relieved only in the workhouse under the terms of the 1834 legislation.

- ‘Workhouse test’, to establish whether someone was able bodied or not, and to ensure that some social categories were only relieved in the workhouse, such as single mothers.

The New Poor Law was run by a Poor Law Commission in London. In 1847 the commission was replaced by a Poor Law Board, and the inmates of workhouses were divided into 7 classes: (a) aged and infirm men, (b) able bodied males over 13, (c) boys 7-13, (d) aged and infirm women, (e) women and girls over 16, (f) all children over 7. The Union officials locally were expected to consult the Commission, and subsequently the Board, in regard to any decision which was not in accord with the principles laid down in the 1834 legislation.

To enforce these principles, it was intended that all 15,500 parishes across the country should be allocated to unions, each with its own workhouse. Each Union was to be managed by an elected Board of Guardians.

In total, 643 unions were formed across the country between 1834 and 1837.

Eight of these were in Nottinghamshire:

- Basford – New union formed in 1836 and took over the existing Basford workhouse, built in 1815. Parts of the original buildings survive as Highbury Hospital.

- Bingham – Union formed July 1836 and a new workhouse for 200 inmates built on a 2-acre site on the south side of the Nottingham Road, bought from Lord Chesterfield. Demolished in 1967.

- East Retford – Union formed July 1836, and a new workhouse built 1836-8 for 200 inmates, at the top of Spital Hill. Closed and demolished in the 1970s

- Mansfield – union formed June 1836. New workhouse built 1837 on the south side of Stockwell Gate, for 300 inmates. On the site of what is now the Mansfield Community Hospital but most of the workhouse buildings have been demolished.

- Newark – new union formed in 1836 using the Newark workhouse and the Claypole workhouse. The Newark workhouse on Hawton Road, partly survives at the rear of a former Castle Brewery

- Nottingham – in effect, two unions were formed:

- the central parishes of St Mary, St Peter and St Nicholas, formed in July 1836 using the St Mary’s workhouse. This proved inadequate, and a new workhouse was built on York Street c.1840. In turn this was demolished in 1896 when the Great Central Railway was built, and replaced with a building 1898-1903 at Bagthorpe, and partly survives within the Nottingham City Hospital complex.

- the outlying parishes of Radford, Sneinton and Lenton, July 1836. A new workhouse for 200 inmates was erected 1837-8 on Hartley Road. Following the extension of Nottingham’s boundaries in 1877 to include these three parishes, the union was dissolved and the member parishes were absorbed into Nottingham Union. The workhouse as converted into a school, and demolished in 1961

- Southwell - in 1836 a new Southwell Union was formed. 41 parishes of the now-dissolved Thurgarton Incorporation, together with Southwell and 18 other parishes, i.e. 60 parishes mainly within about 10 miles of Southwell, were brought together into a union, with the workhouse at Upton.

- Worksop – the union was formed in July 1836, and a workhouse for 400 inmates was erected on East Gate, Worksop, demolished c.1965

The early years of the New Poor Law were particularly fraught, largely because the legislation failed to consider the special needs of industrial and manufacturing areas. It was introduced in the hope of rectifying anomalies associated with the Old Poor Law in rural areas, so that the reforms had little chance of success in industrial areas where, during a trade downturn, hundreds of people were without work, and when conditions improved they rapidly returned to work.

Several of the Nottinghamshire unions ran into difficulties within months of being formed, largely because of a deep depression in the textile industries during the winter of 1837-8, which had an impact on much of the county. The Poor Law Commission in London wanted officials of the new unions to stick to the terms of the legislation, but they struggled to do so as the number of people applying for relief, and being admitted to the workhouse increased.

At Basford Union in 1837 the Poor Law Guardians were overwhelmed with applications for relief from able bodied men. Although initially outdoor relief was refused, the Board quickly wrote to the Poor Law Commission in London asking for consent to allow relief in kind. Although this was initially refused, it was eventually conceded in the light of local conditions. An outbreak of smallpox in the workhouse in 1840 pointed to the problems which could be caused by overcrowding.

Mansfield’s new workhouse was opened in November 1837 and could house 250, but by the time of its opening the worst of the slump for the framework knitters in the town was over. The guardians had resorted to supplying the unemployed knitters with cotton-twist to give them work.

The Nottingham Union had spaces for 260 people, but by late-November 1837

there were 947 people in workhouse accommodation, 208 men employed on road

construction and a similar number being fed daily in a temporary building

on milk porridge and bread at 10 a.m. and meat and vegetable soup at 2

p.m. By December 956 people were in the workhouse, 208 men at work, and

293 people being fed twice a day, but at the same time there was ‘a

very decided improvement in the hosiery trade and indications of a revival

in the lace trade.' Through January and February 1838 numbers fluctuated,

with the number of workhouse inmates rising and falling sharply as a result

of weather conditions. Numbers topped 900 again early in February, and

local statistician William Felkin estimated that in March 1838 1,155 houses

were vacant in the town including numerous retail premises ‘of which

seven were capitally situated in the market-place'. Families had been doubling

up to make ends meet, and ‘the pawnbrokers were unable to receive

the amount of property offered in pledge, and it was thrown away by forced

sales in the public streets'.

By March 1838 the position was improving, and the textile trades gradually

recovered, but Felkin's analysis of workhouse inmates in the spring of

1838 provides an interesting sidelight on Nottingham poverty at the time.

On 17 February 1838 there were 565 inmates. Of these, 42 per cent were

under sixteen, 35 per cent were between 16 and 60, and 22 per cent were

over 60. Of the 240 children 46 had both parents in the house, 65

had been deserted by their parents, 56 were orphans, and 73 had mothers

who were unable to support them; 35 per cent were illegitimate. Inmates

included 160 people there through age and infirmity, 51 through some form

of sickness including blindness, and 56 ‘mild insanity and total

imbecility'. Outdoor relief was being paid in another 596 cases.

Despite the short-term nature of such downturns, it was decided to build a new and larger workhouse, which, when eventually completed after the crisis was over, was seldom if ever filled.

Although the workhouse became a symbol of oppression over time, conditions of life within them were not necessarily as harsh and unforgiving as the 1834 reformers had envisaged, partly because this was almost impossible to achieve given the conditions of life endured by many families in the new urban communities. Both Basford and Southwell workhouses took on the nature of hospitals, although arrangements for sick inmates were far from ideal owing to inadequate sanitation, overcrowding, and a shortage of proper bedding. The standards of school provision for children fluctuated, although they seem to have been quite good in the Southwell Union.

Wherever possible, and sometimes at considerable risk to themselves and their families, people avoided the workhouse. At Basford between 1840 and 1870 no more than 7% of all workhouse inmates were able bodied. Although 1,500 people begged Mayor William Roworth of Nottingham for work in 1839, few families applied to the workhouse for relief if they could possibly avoid doing so. In general the problem of poverty was shifted out of the workhouse and off the rates, but it was not solved.

Later history of the Poor Law

Poor Law Unions in Nottinghamshire (1850).

Poor Law Unions in Nottinghamshire (1909). Click on the images above for larger versions of the maps.

Overtime the role of the workhouse changed from the days when it accommodated anyone in need. From 1909 poor children sent to workhouses were moved to barrack schools, cottage homes or scattered homes, to certified schools or institutions, and to families within and outside the union or with relatives. The Girls Friendly Society in Nottingham fostered, in 1909, four girls aged 14 at its premises 6, Regent Street. A nursery and orphanage in Beeston accommodated 50 children aged 4-6, and the Roman Catholic Nazareth House took 133 girls aged 2-12. Other children lived in cottage or scatter homes or training schools, i.e. Hartley Road. In 1903 2 maternity wards and a labour room were built at the east end of the main workhouse infirmary corridor at Bagthorpe.

With the introduction of pensions, and subsequently of unemployment and sickness benefits, from the early years of the twentieth century, the poor law came increasingly to represent an old and outmoded means of relieving poverty. It was abolished in 1930.

Relief of poverty outside the Poor Law

In Nottingham, the Vestry Society, established in 1713 in the vestry of St Mary's, aimed to promote piety and charity. Membership reached about 40 by the end of eighteenth century and then gradually declined ‘in consequence of the many facilities for effecting the laudable purposes of its institution'. By 1818 it had only 14 members, paying one shilling admission and 2d per week. The purpose of the society was to relieve the distressed who were not receiving parochial pay and to educate the children of the poor. Each member undertook to support one poor boy at school. The Society benefited from various bequests, and in 1810 it purchased the Huntingtonian chapel in Broad Lane and converted it into a schoolroom for the children. In 1818 the society sold the school to the National Society.

By 1839 the annual revenue from endowed charities exclusively devoted to the relief of poverty was £2,272 in Nottingham, of which £1,392 was given direct to the poor and £880 to the support of 15 almshouses. This was a drop in the ocean by comparison with the £20,000 being spent annually by the poor law guardians.

Some better-off families provided for themselves through friendly societies. In 1801 about 7 per cent of Nottingham's population belonged to a total of 51 such societies, while Endowed and Voluntary charities also offered poor relief.

In the absence of adequate state relief, particularly after 1834, poverty was increasingly relieved by charitable means, ranging from soup kitchens during harsh winters, to the systematic organisation of charitable giving through the Charity Organisation Society founded in 1869 to co-ordinate the work of the numerous different groups which sprang up in the years after 1834.

The Nottingham Town and County Social Guild, modelled on the COS, was founded in 1875 to co-ordinate the work of different charities. It was most interested in the environment of poverty, and concerned itself with housing and the provision of recreation and entertainment. For its housing schemes it followed guidelines laid down by Octavia Hill, but the total of its activities represented a poor match for the overall problem of poverty in the town. Straightforward relief to supplement the poor law was given by the Nottingham Society for Organising Charity, while from the 1880s a number of groups appeared in the town promoting socialist ideas and calling for a fairer social distribution of wealth.

The number of charitable bodies in Nottinghamshire rose from 51 in 1840 to 124 in 1850, and their value from £4,806 to £8,003.