Overview

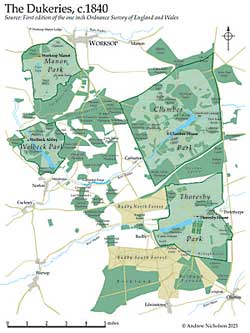

The origins of the Dukeries lay within the confines of Sherwood Forest and were maintained as a game preserve for the aristocracy. Situated in the north and central Nottinghamshire, the Dukeries, refers to an area, south of Worksop, north of Mansfield and extending eastwards to Ollerton. However, the true extent of the estates spills over into Derbyshire and Yorkshire. In 1772 the prolific eighteenth-century letter writer Horace Walpole wrote that ‘in Sherwood Forest lies together four seats of four dukes, Worksop, Welbeck, Clumber Park and Thoresby.’ With an acerbic flourish that was altogether typical he added, ‘I scarce know which I like the least.’

The word ‘forest’ may be misleading, for Sherwood was not a continuous area of great trees; a considerable part of it was heath, covered with bracken and similar vegetation, on poor sandy soil. Even in medieval times there was much open country in the forest area; the great oaks were fewer and further in between than they are today. The forest remained for longer because of its geological make-up, the sandstone being relatively infertile and it was not worth man’s efforts to clear it for cultivation. As a result of this wild animals sought safety within the forest and would only be hunted by royalty.

Nevertheless, parts of the forest were colonised initially by monastic orders, hence Rufford Abbey, Newstead Priory and Welbeck Abbey, but after the Reformation in 1530s, these lands fell into the hands of laymen who converted them into large parks for hunting and pleasure. In 1798 the agricultural reporter, Robert Lowe estimated than more than 10,000 acres had been taken into these estates during the eighteenth century – much of this must have been an encroachment on the Forest.

In a country with only 24 dukes, it is peculiar that four of them lived cheek-by-jowl in Sherwood Forest: the Dukes of Kingston, Newcastle, Norfolk and Portland. So, who were these Dukes and how did they come by their estates?

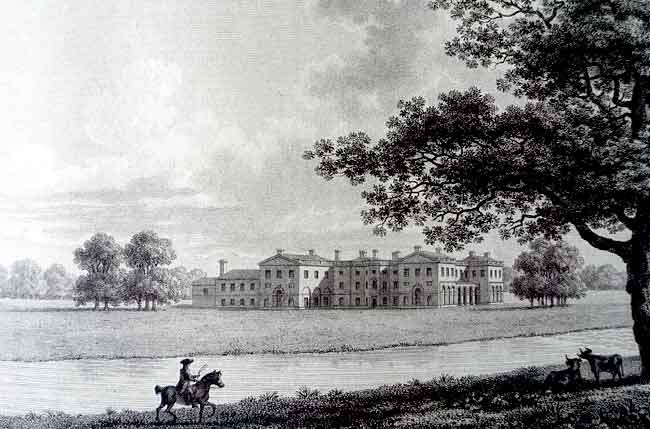

The Kingston’s country seat was at Thoresby Hall. They were a Nottinghamshire family, originally Earls, but raised to the dukedom in 1715, and the only one of the dukes permanently resident in the area, although they had another house at Holme Pierrepont, near Nottingham. The original Thoresby was built in 1671 by the Pierreponts. The house was remodelled between 1685 and 1687, at the same time permission was granted by the Crown to enclose 1,200 acres of the Forest as Thoresby Park. During the life of the second duke (grandson of the first) the Hall was destroyed by fire in 1745 and the building of a new house was undertaken and completed in red brick in 1771 at a cost of £17,000 with a further £13,000 for the complex of kennels and stables.

Evelyn, 1st Duke of Kingston and Thoresby Hall by Peter Tillemans, c.1725 (Courtesy of the British Library).

Evelyn, 1st Duke of Kingston and Thoresby Hall by Peter Tillemans, c.1725 (Courtesy of the British Library).Kingston died in 1773 leaving a widow and the property in a mess. The duchess, accused of bigamously marrying Kingston retired to the continent and on her death the property came into the hands of Charles Meadows, a nephew of the duke, who took the name of Pierrepont and who in 1806 was created Earl Manvers. He instigated some work on the property but mainly to increase the agricultural potential of the estate.

Thoresby Hall, c.1905.

Thoresby Hall, c.1905.In 1864 the third Thoresby Hall was commissioned by the third Earl Manvers who employed the celebrated High Victorian architect, Anthony Salvin. It was considered the most ambitious Victorian house in Nottinghamshire. The house was built of Steetley stone between 1864 and 1875 and a fine memorial to the Victorian age. It cost £17,000 with another £37,000 being laid out on stables, a woodyard and kennels.

The fourth Earl Manvers succeeded his father in January 1900 and after his death in 1926 the estate was inherited by the fifth Earl. During the Second World War, the army were accommodated there, along with scores of horses. The house descended to the 6th Earl Manvers, Gervas Pierrepont, who died in 1955 without a male heir and the title thereby became extinct. He was succeeded by his wife, Countess Manvers and daughter, Lady Rozelle Raynes. Lady Raynes died in 2015.

It is many years since a duke has lived at the Hall. Thoresby Hall was sold in 1998 to Warner Hotels. The estate was latterly divided into two between Hugh Matheson, High Sheriff of Nottinghamshire (1997) and Deputy Lieutenant of Nottinghamshire (2004) and Ian Thorn.

Whereas Thoresby Hall still stands, Clumber House has gone forever, all that remains is the park. At Domesday (1086) the land was in the possession of the King and his powerful kinsman Roger de Busli. The Cavendish interest in Clumber dates from 1629, when the Earl of Newcastle acquired Warr Wood. The family continued to acquire further territory through the marriage of a daughter to John Holles who was created Marquis of Clare and Duke of Newcastle. Through his influence as ‘steward, keeper and warden of Sherwood Forest’, he obtained in 1707 a license from the Crown to enclose 3000 acres of his property into a Royal deer park, for which he was granted £1000 annually by Queen Anne in 1709. The park was enclosed by a fence and contained 400 head of deer.

John, Duke of Newcastle, died in a riding accident and the property passed to his nephew, Thomas Pelham-Holles, created Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne in 1714. He was a major political figure who spent his life mainly in London. When he did visit the countryside, it was to his estate in Sussex or Claremont in Surrey. When he visited Nottingham, he stayed at Nottingham Castle, which he had inherited. He did not have the money to build a house at Clumber. This situation changed when, in about 1760, he transferred the property to his nephew and heir, Henry Fiennes Pelham-Clinton, the 9th Earl of Lincoln.

Clumber House, c.1780.

Clumber House, c.1780.The second Duke of Newcastle, as he became in 1768, had little interest in politics and he sold Claremont. He intended to create one of the largest houses in the Dukeries on the site of the existing manor house. From 1759, work on the house proceeded, under the supervision of a carpenter and builder named Fuller White (although he is likely to have been working to plans from the architect Stephen Wright). White was dismissed in 1767 and Wright took charge of the project, replacing some of the 1760s features in the 1770s. The project was still not complete when Wright died and some features in and around the park may have been designed by his successor, John Simpson, in the 1780s. The full potential of the site was realised with the construction of the lake between 1774 and 1789; the waters covered 83 acres and went past the house to almost Clumber Bridge, which had three semi-circular arches. The transformation from a ‘black heath, full of rabbits, having a narrow river running through it, with a small boggy close or two’, to an area of ten to eleven miles round with a magnificent mansion, noble lake and river and good agricultural land was noted by several contemporaries. Under the second Duke, Clumber became a major agricultural unit, with timber carefully cultivated, pasture land, as well as land under cultivation.

No sooner had there been improvements made than the incumbent died leaving the property in the hands of someone not as competent. The third Duke died in 1794 leaving his 10-year-old son in charge. From 1809 the fourth Duke made a number of improvements but he also ran the estates into severe financial difficulties by purchasing other estates which stretched his finances too far.

On his death in 1851, the estate passed to his son, the fifth Duke. This was something of a poisoned chalice for him, but he did his best to restore family affairs. In 1857 he invited the architect Sir Charles Barry to redesign the house in the Italian style but this was never acted on. The fifth Duke died in 1864 and was succeeded by his son, the sixth Duke, who through his gambling and racing speculations very nearly brought the estate to its knees. A new trust was established to run the estate, and with the land sales the family pulled through. He died in February 1879, two months before much of Clumber was badly damaged in a fire which destroyed twenty of the 105 rooms and numerous artefacts, including 72 pictures.

Clumber House by Ernest Haslehust (c.1913).

Clumber House by Ernest Haslehust (c.1913).The seventh Duke was still not of age when he inherited the estate in 1879, but his trustees took the immediate decision to hire the architect Charles Barry the younger to rebuild the house, although they rejected his plan for a massive tower over the western entrance front. In 1883 the seventh Duke owned 34,467 acres in Nottinghamshire, mostly in the Dukeries, with some property in Nottingham, with a gross income of £74,547. Despite increasing financial difficulties, in 1886-9 he built the church of St Mary the Virgin, Clumber Park, near the house.

Clumber House was not the largest of stately homes, being much smaller than neighbouring Welbeck Abbey. However, it had a vast collection of treasures. It was the last of the great estates to be won from the native forest. During the construction of the lake a broad woodland was planted.

The seventh Duke of Newcastle died in 1928 and with no children to inherit, the title passed to Lord Francis Pelham Clinton Hope, and Clumber to his nephew, the Earl of Lincoln (son of the new Duke). In 1936 Lincoln accepted that the spiralling costs of upkeep were beyond him. He planned to demolish Clumber and build a more modest house in the park. The contents were auctioned and in 1938 the house was demolished. The smaller house never materialised.

Clumber was requisitioned in the Second World War, and the ninth Duke, who succeeded in 1941, sold what was left in 1946 to The National Trust, who continue to run the park.

Welbeck Abbey dated originally from the twelfth century, and some of its cloistral buildings survived into the eighteenth century. In 1539 the religious house was dissolved by Henry VIII and granted to Richard Whalley. Through marriage the estate passed to the third son of Bess of Hardwick, Sir Charles Cavendish, whose son, William, was created Duke of Newcastle in 1664. He died in 1676 and was succeeded by his son Henry; two generations later, Lady Henrietta Cavendish-Holles, Countess of Oxford, owned the estate. Her cousin, Thomas Holles had been given Clumber. It was Lady Henrietta’s daughter, Lady Margaret Cavendish Harley, who married the second Duke of Portland, which is why the house became associated with the Portland rather than the Newcastle dukedom. Lady Henrietta refurbished what came to be known as the Oxford Wing in the 1740s and employed Francis Richardson to landscape the park. He converted various tracts of unproductive land into closes which were then hedged, planted and cultivated. A pleasure garden was formed around the house.

Welbeck Abbey from the south-west, c.1840.

Welbeck Abbey from the south-west, c.1840.The third Duke of Portland, who was Prime Minister in 1783 and between 1807 and 1809 completed the remodelling of the south wing in the 1770s. He employed Humphry Repton to create the Great Lake as a focal point of a fully landscaped parkland. He was a notable farmer who created the water meadows alongside the River Maun at Clipstone from unproductive heathland. Despite all of his inherited wealth, he managed to leave his heir, the fourth Duke, with debts amounting to £512,000 in 1809.

The fourth Duke, William Henry Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck, (Lord Privy Seal in 1827), immediately began selling land and was able to clear a large percentage of his debts. He was also a much more careful manager of his property and was able to capitalize on the rents from his London properties and improve his income. He had nine children, four boys and five girls. The eldest and third eldest son predeceased their parents. With his estates looking good he wanted to pass on the management of the estates to his eldest son and heir, but unfortunately the son would not play ball. The son died before his father, who was left to soldier on for another decade, and when he finally died, his heir, now the fifth duke, a handsome and generous man with an exaggerated shyness, withdrew from the limelight. He chose to occupy only four or five rooms in the house, ‘which were scantily and almost poorly furnished’ …and to communicate with the outside world only through letters. The rest of the mansion lay empty or stacked with countless treasures.

Bust of the 5th Duke of Portland.

Bust of the 5th Duke of Portland.The fifth Duke was an extremely wealthy man, with money coming from rents on his London properties, holdings and investments. Whereas previous ancestors had spent money unwisely, the fifth Duke used it on a series of unusual building works. He developed Welbeck, most of which, luckily still exists. Many of his building projects took place underground, including a suite of three library rooms, a chapel later converted to a ballroom, an underground railway and airy tunnels, which were heated by hot air and lit by thousands of gas lights. Perhaps the strangest construction was a tunnel that ran for over a mile from Welbeck, so that Portland could reach the railway station at Worksop, without being seen, at which point his closed carriage would be placed onto a train, and he would be whisked off to his London house. The house and grounds were in a terrible state, except for the rooms in which the fifth Duke had lived, all the others were bare – no furniture or pictures to be seen – but all were painted pink! He died at his London house in 1879, leaving Welbeck in a complete mess. He was unmarried and childless, so the dukedom passed to his first cousin, once removed, William John Arthur Charles James Cavendish-Bentinck.

6th Duke of Portland.

6th Duke of Portland.The sixth Duke was the complete antithesis to his predecessor, and brought the estate to a fine condition; these were the golden years of Welbeck. The duke married, Winifred Dallas-York, and had three children. They were very hospitable and entertained royalty and the great and the good of the period. The duke continued at Welbeck for 63 years. He was a great horseman and brought the stables and riding school erected by his eccentric predecessor, to life. The riding school was the second largest in the world and one of the uses made of this great building was to host the Welbeck Tenants’ Agricultural Society luncheons, which the duke and his wife held every year. The sixth duke was a very well-liked landlord and together with his wife, they improved the lot of many of their tenants and those around the area. The Orthopaedic Hospital at Harlow wood, south of Mansfield, came into being in 1929 as a direct result of the efforts of the Portlands, as did many other institutions and schemes for the welfare of children, miners and soldiers.

The Duke played a prominent role in Nottinghamshire public life during the first half of the 20th century. He served as an alderman of the County Council for nearly 40 years, was Lord Lieutenant of Nottinghamshire from 1898-1939, and President of Nottingham University College from 1903 to 1943. He was also honorary colonel of the 4th and 7th Sherwood Foresters, Provincial Grand Master of the Nottinghamshire Freemasons (1898-1933), President of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire (1897-1943) and President of the North Midland Divisional Council of Y.M.C.As.

On the death of the sixth Duke in 1943, the dukedom passed to his eldest son, William Arthur Henry, Marquess of Titchfield. The seventh Duke of Portland had built Welbeck Woodhouse, a large modern house within the grounds of the Abbey in 1930-2. His mother, the Dowager Duchess of Portland, continued to live in a wing of Welbeck Abbey until her death in 1954. The Dukedom of Portland became extinct following the death of Victor Cavendish-Bentinck, 9th Duke of Portland, in 1990.

Welbeck College, established at the Abbey to provide A-level education for boys planning to join the technical branches of the British Army, remained on the site from 1953 until 2005.

Lady Anne, the unmarried elder daughter of the 7th Duke of Portland, lived at Welbeck Woodhouse until her death in 2008. Her nephew, William Henry Marcello Parente (born 1951) inherited and moved into Welbeck Abbey making it a family home once again. The family-controlled Welbeck Estates Company and the charitable Harley Foundation have converted some estate buildings to new uses. These include the Dukeries Garden Centre in the estate glasshouses, the School of Artisan Food in the former fire stables, the Harley Gallery and Foundation and the Welbeck Farm Shop in the former estate gasworks and a range of craft workshops in a former kitchen garden. The house remains private, although tours of the principal rooms are briefly open to the public each August.

The final Dukeries estate was Worksop Manor, a house built in the 1580s by Robert Smythson for the sixth Earl of Shrewsbury.

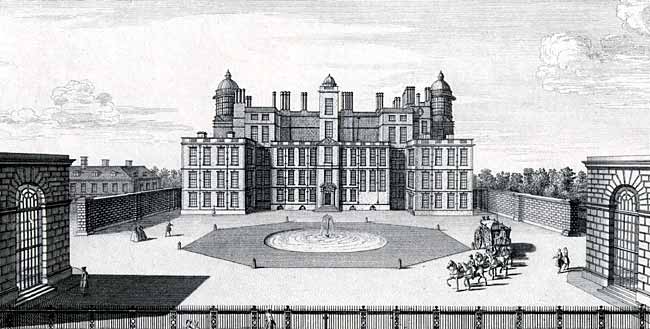

The north front of Worksop Manor by Samuel and Nathaniel Buck, 1727.

The north front of Worksop Manor by Samuel and Nathaniel Buck, 1727.The seventh Earl’s daughter married in 1606 Thomas Howard, earl of Arundel, and carried into his family estates in Yorkshire, Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire, rich in mineral (lead, coal and iron) and including Worksop. The extent of the property also transformed the family’s territorial power. One result was an increased importance for Worksop, which became the family’s main seat in the eighteenth century.

Worksop Manor was a great Elizabethan house with over 500 rooms and was the principal seat of the Earls of Shrewsbury. It is said to have looked like a castle when seen from a distance. This was because of its extreme height, over 90 feet high topped by towers and chimneys.

In 1660 the Dukedom of Norfolk was restored to Thomas Howard’s grandson, having been defunct since the 4th duke was beheaded in 1572 for his role in the affairs of Mary, Queen of Scots. We know it today only from illustrations because between 1701 and 1704, the eight duke (who succeeded in 1701) almost doubled the size of the original Elizabethan house – the centrepiece was a second-floor gallery and the interior was decorated in the baroque style. The duke also built the service and stable wing on the east side.

In 1732 the 8th duke died and was succeeded by the ninth duke who, in spite of being a recluse, continued to remodel Worksop, which was his chief seat. The alterations were nearly finished when a fire broke out destroying the vast stock of treasures.

The duke immediately decided to rebuild the house, on an even grander scale. The driving force behind the building was the duchess. Architect James Paine was employed. He had been responsible for the decorations in the old house and had worked at nearby Chatsworth, Kedleston and Serlby Hall, home of the Viscounts of Weymouth, north-east of Worksop.

Paine designed a new house, more a palace, on an even grander scale than the previous house. It was intended for the Norfolk’s nephew, Edward Howard, as heir presumptive but he died of measles in 1767. The design contained four ranges, or fronts, of 300 feet in length, with two internal court yards divided by a central ‘Egyptian Hall’, 140 feet long. The foundations were laid in 1763 and the north range was completed in July 1794. Over 500 men were employed on the site.

Had it been completed the new Worksop Manor would have been the largest country house since Blenheim in the first decade of the eighteenth century. It was intended as a visible proclamation of the duke’s position as the premier duke, built with the profits of his Sheffield mineral resources. However, it was criticized for being built too close to the Worksop-Mansfield Road, instead of being surrounded by parkland.

By the nineteenth century the house had become a white elephant, the tenth and later Dukes preferred Arundel Castle, rarely visiting the Manor. The grounds were let off as agricultural land and in 1839 the 12th duke sold the estate to the 4th duke of Newcastle for £375,000 and since he had no use for another house so near to his home at Clumber he had Worksop Manor demolished. The servants’ quarters were spared, however, and were remodelled to form a relatively modest house. The estate was again sold in 1890, by the seventh Duke of Newcastle, to John Robinson, a well-known public figure and brewer in Nottinghamshire and whose family still lives at Worksop Manor.

The sale of Worksop Manor by the Duke of Norfolk to the Duke of Newcastle in 1839 saw the passing from the Dukeries of a second of the dukedoms following Kingston in 1773. The four estates remained, although two were now owned by the Dukes of Newcastle, and the Thoresby title was an earldom. Even so, In the 1880s passing travellers would still have found little to suggest that the estate system was under threat except perhaps at Worksop.

The Dukeries estates were a reflection of one of the essential principles on which the English aristocracy were grounded until at least the 1880s – the large house, suitable in size and design to the aristocratic standing of the owner, set within its own landscaped park, and surrounded by a multitude of acres belonging to the owner, so that in whichever direction he looked he could claim it to be his own. From these estates the owners enjoyed a substantial income. Often the houses were built, rebuilt or remodelled, often more than once during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, sometimes at crippling costs to the owners.

Conclusion

However, the cold winds of change were beginning to blow and by the 1880s, agriculture was depressed and land value was falling. Death duties introduced in 1894 were coupled with a decline in the social and political position of the greater landowners, which made land less attractive than secure and often higher yielding assets were available elsewhere. Changes in the law, particularly the Settled Land Act, of 1882 enabled owners to dispose of their property more easily. Previously legislation acted to fuse estates together and made disposal difficult.

Before 1914 the landowners feared for the future, but after 1918 the situation became much bleaker. Across the country landowners began to sell land and houses. Nottinghamshire and the Dukeries were not immune and none of the Dukeries estates have survived intact.

In 1883 the Dukeries estates totalled one-fifth of Nottinghamshire, today they have gone. The breakup of the Dukeries estates began in the 1930s when Clumber was pulled down and the Newcastles departed and their title became extinct. Clumber was requisitioned in the Second World War, and the ninth Duke sold what was left to The National Trust in 1946. He went to live in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) and on his return bought a modest place in Boyton, Wiltshire. He died in 1988 and the dukedom is now extinct. The family papers and portraits are now held at the University of Nottingham.

The sixth Duke of Portland stayed at Welbeck from 1879 and the house was remodelled in 1900-2 following a disastrous fire. The seventh Duke built a house in the grounds, known as Welbeck Woodhouse, in the early 1930s.

On the seventh Duke’s death in 1977 his daughter, Lady Anne Cavendish-Bentinck, inherited the family estates and on her death in 2008 they passed to her nephew, William Parente, who has made Welbeck Abbey a family home.

The Dukedom became extinct in 1990 on the death of William Cavendish, the ninth Duke of Portland.

Thoresby only finally passed out of the hands of the Pierreponts and their successors in 1988. The third Earl of Manvers died in 1900. The property was requisitioned during the Second World War when forty officers and several hundred men occupied the top floor. The Manvers title died out in 1955 and the heirs managed to hold on to some but not all of their land. The owners no longer hold a major aristocratic title and the contents were sold in 1988 by Lady Rozelle Raynes, the only daughter of the last earl. Today Thoresby is a luxury hotel which is ironic as the third Earl had valued his privacy so much that he opposed the building of a coal mine within the estate and was unwilling to see coal mined at Thoresby.

Worksop Manor was sold in 1890 to Sir John Robinson (chairman of Home Brewery Co Ltd) and it ceased being the seat and inheritance of a Duke. It remains a private house and is home to the Worksop Manor Stud.

Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries the Dukeries were built up as large estates set in their own grounds and parks, but since 1880 much has changed in the socio-economic lives of the aristocracy. Nevertheless, passing north through Nottinghamshire even in the 21st century, we can still see on the ground the living evidence of the Dukeries; it is still possible to visit Clumber Park courtesy of the National Trust, Thoresby can be visited courtesy of Warner Hotels, and tours of Welbeck Abbey’s state rooms have been run every summer since 2012.