Overview

The historic parish of Worksop covered 18,220 acres (7,373 hectares) and was the largest in Nottinghamshire; in addition to the town it comprised the settlements of Radford, Ratcliffe, Darfould, Sloswick, Rayton, Kilton, Manton, Gateford, Hagginfields, Shireoaks, Clumber, Hardwick and Osberton-with-Scofton.

Early Worksop

Aerial archaeology has revealed extensive brickwork plan field systems around Worksop, most likely dating from the late Iron-Age and Romano-British periods. A cropmark enclosure at Raymoth Lane was recently excavated and the faunal remains recovered suggest that "animal husbandry played a greater subsistence role than agriculture" in the area. The site also produced a Roman pottery kiln and evidence of metal working.

Other Romano-British finds made locally include a fragment of the side of a lead coffin unearthed at Gateford and coin hoards found in Osberton and Ranby.

Apart from a 9th century strap end discovered by a metal detectorist, evidence of Anglo-Saxon activity is limited to placenames such as Osberton, Kilton, Manton and Scofton. The name 'Worksop' itself derives from Weorchope, or Weorc's valley.

Medieval Worksop

The west front of Worksop Priory.

By the late 11th century Worksop formed part of Roger de Builli's vast estates, which he ran from his headquarters in Tickhill. Domesday Book (1086) records 22 sokemen, 24 villeins and eight bordars here.

Medieval Worksop was dominated by the castle and the priory. The surviving earthworks of the castle suggest it was of ringwork type rather than the more common motte and bailey. The castle buildings had, however, disappeared by the 1540s when John Leland observed that it was "clene down and scant knowen wher it was."

The manor had passed to William de Lovetot by the early 12th century and in the 1120s he founded and endowed a priory of the Augustinian order. The priory stood a distance from the castle and the small settlement of Radford developed around it. The building of the priory was a protracted process and culminated in the erection of an impressive gatehouse in the 14th century.

The town itself grew up between the castle and the priory. The nucleus of medieval Worksop was Bridge Street and Potter Street; the latter led directly to the twin township of Radford which from 1296 held a weekly Wednesday market and an annual fair.

16th/17th century Worksop

Leland observed in 1540 that Worksop was "a praty market of 2 streates and metely well buildid."

Worksop Priory was closed in 1539, and the Prior and 15 monks were pensioned off. All the Priory buildings, except the nave and west towers of the church, were subsequently demolished and the building materials taken and reused elsewhere.

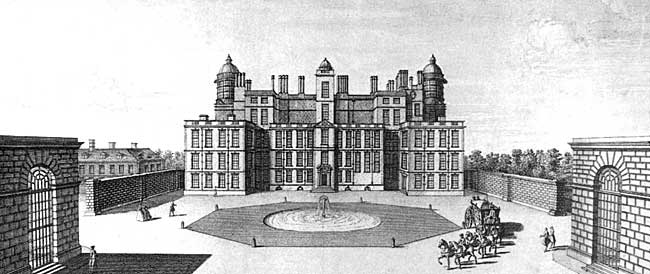

Worksop Manor, dating from the 1580s, as it appeared in the mid-18th century.

The priory's land and property in the town were granted to Francis, 5th Earl of Shrewsbury. In the 1580s Shrewsbury built a magnificent house to the south-west of the town. Worksop Manor was designed by Robert Smythson and was described in 1636 as "a very stately house ... build of freestone, being very pleasantly situated upon a hill, with gardens corresponding to the same." Manor Lodge, a possible hunting lodge associated with the house, was built at the same time.

By the 1630s ownership of Worksop had passed to the Earl of Arundel and he commissioned John Harrison to survey his property in the area. The survey describes Worksop in great detail. The manor house set in an extensive park of 2,300 acres that was over seven and a half miles in circumference. The houses of his tenants included 'Jesus house', a six-room dwelling occupied by Henry Cole, a farmer of 200 acres of arable who grazed his sheep on Manton sheepwalk.

The survey also reveals early industry in the town. Bracebridge mill, a corn-grinding water mill, is mentioned, along with the stone-built Manor Mill situated near to Castle Hill. There was also a kiln and a malthouse. A dye house and a tenter green, where lengths of cloth were stretched out to dry, indicates at least a small-scale cloth industry in the early 17th century. It is clear, however, that most people in Worksop at this time derived their livelihood from the land. Most people will have been involved in mixed farming, and there was one unusual crop mentioned in the survey: liquorice.

The Hearth Tax returns of 1674 record 176 households in Worksop, making it the fourth largest urban settlement in Nottinghamshire after Nottingham (967 households), Newark (339) and Mansfield (318). Based on these returns the population has been estimated to have been 748.

18th century Worksop

The eighteenth century saw important changes in the town. An ecclesiastical return of 1743 records 358 families in Worksop, suggesting a population of 1,500. By 1801, the population had more than doubled to 3,391. The town started to expand and new streets lined with brick and tile houses were developed to accommodate the growing population.

Early 19th century depository over the Chesterfield Canal at Bridge Place.

Transport links improved when the Chesterfield Canal was completed in 1777 and its opening had an immediate effect on the town’s economy. The canal ran for 46 miles contained 65 locks, 69 bridges, two tunnels and connected the River Trent with Retford, Worksop and Chesterfield. The Gentleman’s Magazine of 1777 observed that it was "already of prodigious advantage to the neighbouring country in conveying limes, coals, and other heavy articles, which are now carried at about one fifth part of the usual price of land-carriage and altogether as expeditious." The most visible sign of the new age in transport was housing and industrial development to the north of the canal in an area called The Common.

William Toplis of Cuckney attempted to introduce manufacturing industry to the town in 1792. Two textile mills were erected “for the purpose of spinning, worsted, and weaving filleting, turban stuff, sashes, etc.” One of the mills was on the south side of the canal at Bridge Place, the other was most likely situated on Mansfield Road. However, the enterprise was short-lived as the mills both closed within three years of operation and were converted to mill corn. Nevertheless, the experiment did leave a more tangible legacy in Norfolk Street and the 60 houses along it that were built to house mill workers.

19th century Worksop

The population of Worksop increased markedly in the 19th century, from 3,291 to 16,455. The period also saw a fundamental change in the nature of the local economy. At the start of the 19th century the economy was largely agricultural in nature: malting, corn milling and timber-working. However, by 1900 the majority of the workforce was employed in the mining industry.

The railway station opened in 1849 and heralded a new era in travel. The station was built in Jacobean style of local Steetley stone and has been described as “the most architecturally elegant station on the [Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire] railway.” This is not surprising as it was the local station of the Duke of Newcastle and many of his guests, including the Prince of Wales, passed through it on their way to Clumber House.

By the late 19th century Worksop had become a key part of the local tourism industry and was commonly known as ‘The Gateway to the Dukeries.’ Popular tours of the Worksop, Welbeck and Clumber country houses and associated parkland started from the town and tour operators were entrusted with the keys to the gates.

A former malthouse on Eastgate (photograph courtesy of Jane Sumpter).

The railway stimulated further building on the north side of the town, along Gateford Road and Carlton Road, and also had a major impact on the malting industry. Before the arrival of the railway, malting was largely seasonal but from now on not only could grain could be obtained from a far wider area but the market for the malt was also much wider. These factors led to a longer season and thus justified the construction of large-scale maltings which operated for much of the year. The largest malting buildings were the Clinton Maltkilns which were built near the station on Carlton Road in 1852.

Coal had been carried on the Chesterfield Canal for many years but it was not until 1854 when the first shaft at Shireoaks Colliery was sunk that the coal industry truly arrived in Worksop. In 1861 over 200 men were employed at the colliery and “within two years of raising its first saleable coal it was already the largest single source of employment in the district;” by 1871 over 600 worked at the pit. Other collieries followed: Steetley colliery started producing coal in 1876 and the first shaft at Manton was sunk in 1898, although coal production only started in 1906.

Local government had to adapt to cope with the changing demands of the growing town. Historically, it had been centred on the meetings of the parish vestry, the magistrates and the Court Leet but their inadequacies were all too obvious as the town grew in size. The first Local Board of Health was elected in 1852 and became a town council of nine members in all but name. It successfully organised an efficient system of sewage disposal and drainage and was eventually replaced by an Urban District Council.

Worksop’s growing importance was reflected in buildings like the Corn Exchange at the top of Potter Street, built in 1851. Initially, the corn exchange was situated on the ground floor and the first floor was used as an assembly room which hosted evening balls, public meetings and a variety of social events and entertainments. The assembly room was also used as the location for both the County Court and the Magistrate’s Court. A Reading Society and Mechanics Institute were formed and they were instrumental in establishing a library and news room elsewhere in the Exchange. Ownership of the Corn Exchange passed to the Local board of Health in 1882 and the building became the Town Hall.

Serious outbreaks of disease in the 19th century and a continuing problem with sewage disposal led the Local Board of Health to devise a scheme to use treated waste and sewage to fertilise farm land in the area. An Italian Romanesque style pumping station at Bracebridge formed the focal point of the new system which was completed in 1881.

The 19th century was less kind to Worksop Manor. Work had started on rebuilding the house in palatial style after a disastrous fire in 1761, although only the north wing of the planned quadrangular house was completed. However, in 1840 the Duke of Norfolk sold the estate to the Duke of Newcastle and having no use for the house he ordered its demolition. The domestic quarters survived and were converted into a large house which now bears the name.

Modern Worksop

On the 1 October 1931, Worksop received its Charter of Incorporation and was awarded the status of a borough. Worksop became part of Bassetlaw District in 1974 and with a population of 36,000 is the largest town in the district.

The last 30 years have seen the dramatic decline of Worksop’s most important industry, coal. Steetley Colliery was the first to be closed in 1968. Shireoaks was shut down in 1991 and was followed by Manton in 1994.

Worksop’s economy now depends on food production, retail and distribution.

Sources

- Michael J Jackson, Bygone Worksop, The Worksop Archaeological and Local History Society, 2005

- Michael J Jackson, Victorian Worksop, The Worksop Archaeological and Local History Society, 1992

- Michael J Jackson, Worksop of Yesteryear, The Worksop Archaeological and Local History Society, 1968

- Gill Stroud, Nottinghamshire Extensive Urban Survey Archaeological Assessment: Worksop, Nottinghamshire County Council, Environment Department, 2002

- W F Webster, Nottinghamshire Hearth Tax: 1664 - 1674, Thoroton Society Record Series, Volume XXXVII, 1988

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Sam Glasswell of Bassetlaw Museum and Jane Sumpter for information for this research pathway. The Worksop Heritage Trail website contains a wealth of information on the history of Worksop and the surrounding district: