Overview

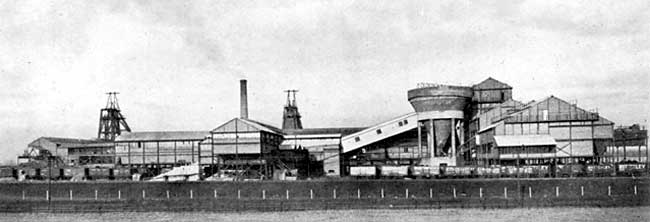

Ollerton Colliery, 1938.

Origins

Coal has been mined in Nottinghamshire for many centuries, but for a long time this was simply surface mining. Coal was probably being mined around Cossall and Selston in the 1270s. Certainly mining was taking place on a significant scale at Selston in the reign of Edward I. Mining at Cossall is again documented in the mid-14th century. The Carthusian religious house at Beauvale had a particular connection with coal mining, especially at Newthorpe, Selston and Kimberley, in the reign of Richard II.

The idea of mining deeper, sinking shafts, making drains and using timber for props, gradually gained acceptance, including the use of the sough – a method of gravity draining. In part, this was encouraged in the Selston area by a ready demand for coal from Nottingham by the 15th century. Perhaps recognising this market, in 1457 the priory of Lenton acquired from the Carthusians at Beauvale a portion of their coal at Newfield, on a lease for seven years. The Carthusians retained an interest in coal mining until the Dissolution of the Monasteries, when they were making money from a mine at Kimberley and taking rent from another at Selston.

Early modern coal mining

From the sixteenth century new methods of mining enabled work to take place immediately below the surface, but it remained the case that mines were shallow, and only coal quite close to the surface was worked out. Miners simply moved to another area rather than mining deeper, partly because there were plenty of easily worked surface seams and partly because the technology, particularly for draining mines of water, remained primitive.

Mining developed towards the end of the 15th century in and around Wollaton, and during the 16th century coal was worked both at Wollaton and Strelley. The mines were sufficiently profitable to create tension between the Willoughby family of Wollaton, and the Strelley family, who began mining around their manor of Strelley c.1540.

Prior to the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s and 1540s, the prior of Lenton had allowed Sir Henry Willoughby, then lord of the manor of Wollaton and owner of a mine within the manor, to make a sough from his own coalmines through various lands of the priory in order to remove water from the mine. At the Dissolution the reserved rent was commuted to 12s a year and paid to the king by Sir John Willoughby.

Subsequently the Willoughbys accused the Strelleys of diverting water into their mines in an attempt to ruin their trade.

In the reign of Edward VI (1547-53), Henry Willoughby of Wollaton sought permission to make a new sough on land owned by the king and previously in the ownership of the Lenton Priory. In fact, he was significantly increasing the mining on his Wollaton land, and subsequently Sir Francis Willoughby helped to finance the building of Wollaton Hall by selling coal into Lincolnshire, partly in return for the Ancaster stone with which the hall was faced. The Strelleys were less successful and by 1620 had mortgaged their mines to London merchants who subsequently foreclosed on them.

Nottingham corporation funded some trial borings for coal on land owned by the corporation in the 1590s, and they were still hoping to find coal in the 1630s, prospecting on wastes and woodlands in their ownership. By the 17th century coal mining was one of the most important industrial interests in Nottinghamshire, with new mines opened in the Hucknall area.

Most coal was sold locally to domestic consumers, but efforts were made from the 17th century to use coal commercially. Glassworks were established at Wollaton in 1615, the aim being to use local coal in the glass making process. The glass was to be sold on the London market. It was calculated that it would cost £1 2s 7d to sell a ton of Wollaton glass in London. The enterprise was not successful and had closed by 1617.

In 1601 the Willoughbys leased their Wollaton pits to Huntington and Nicholas Beaumont, father and son, on a 21 year lease. Two years later the Beaumonts also leased pits in Strelley which had been acquired in 1597 by the Byrons of Newstead. In 1604 Huntington Beaumont undertook to deliver 7,000 loads of coal to Nottingham annually, but meeting this target proved impossible. Beaumont’s financial backers pulled out and by 1618 he was imprisoned in Nottingham for debt.

Despite Beaumont’s failure coal mining continued and the collieries at Cossall and Trowell were in production during the 1650s and 1660s. They declined after 1672 and mining was not resumed at Trowell until 1720. The Willoughbys were making £1000 a year or more profit in the early 1730s but rather less later in the decade.

In the middle of the 18th century, Charles Deering recorded that Nottingham was well supplied with coal from neighbouring pits, particularly those of the Middleton family: ‘there are coal mines within 3, 4, 6 & 7 Miles, North-West and West of this Town, which being work’d furnish to it Plenty of Coal, at a reasonable Rate, for they are never above 4d. to 6d per Hundred unless when a wet Winter Season has made the Roads very bad, for which great Advantage Nottingham owes an everlasting Gratitude to the Memory of the Late, and the Personal and Family, of the Right Honourable the present Lord Middleton.’

Improved technology permitted deeper mining from the early eighteenth century, particularly through when steam engines were developed, which were powerful enough to raise water efficiently and drain coal mines. Deeper mining was mostly inhibited by the need to drain water from the mines, and also by the problems created by the build up of gasses, and, following from this, explosions, since miners used naked flames to light their way underground.

The Nottinghamshire coalfield lies on the eastern side of the Erewash Valley coalfield which begins on the Derbyshire side of the county boundary. The western part of the coal field is the shallowest, and this has historically made mining easier and cheaper in the Derbyshire area. This geological structuring was recognised by Robert Lowe in 1798 when he wrote that ‘the line of coal begins a little north of Teversall, runs about south and by west to Brookhill; then south to Eastwood; afterwards about south-east, or a little more easterly to Bilborough, Wollaton and the (River) Leen. This line is scarce above a mile broad in this county, and above the coal is a cold blue or yellow clay.’

Competition in the coal trade was increased by the building of canals. When the Erewash Canal, running from Trent Lock to Langley Mill, opened in 1779, coal proprietors on the Derbyshire side of the river Erewash were able to sell their coal in Nottingham via the canal and then the River Trent, and to undercut their Nottinghamshire rivals. The Nottingham canal opened in 1796, which enabled the pits in Wollaton, Strelley and Bilborough, to compete for business in the Nottingham market. By 1798 it was reported that prices in Nottingham had fallen significantly.

The 19th century

The Brinsley Colliery headstocks date from 1875.

By the early 19th century there were mines being worked at Beggarlee, Bilborough, Brinsley, Eastwood, Greasley, Hucknall, Skegby, Trowell and Wollaton.

The main mining method was still to dig new pits rather than go deeper – hence the large number of relatively shallow pits, and using these rather primitive methods production rose significantly:

1750 = c.140,000 tons p.a. on the 2 coalfields

1799 = 384,000 tons p.a.

1816 = 1.6m tons p.a.

As a result production in Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire increased from about 3% to about 6% of national production. Most of it was sold within the region along the canal and river network. At this time Erewash Valley meant in effect the 900 or so square miles on the Derbyshire side of the valley.

The rise in production was not sustained and by 1830 the figure had fallen below 6% of national output.

From the 1840s various developments in technology and carriage (notably the railway) made it financially viable to begin mining at deeper levels. As a result, coal mining spread east, to the deeper seams of Nottinghamshire on the eastern side of the Erewash Valley coalfield. This was feasible only by sinking deep mines, at greater capital cost, although by contrast with what would come later coal mining was relatively easy on the west side of the Erewash Valley because here the coal outcropped near to the surface and so capital requirements were relatively limited. This also meant that companies were small, output was limited, and the industry was technologically under-developed until well into the nineteenth century.

The 2000 square miles of deep coal veins on the Nottinghamshire side of the Erewash were a resource waiting to be exploited. Entrepreneurs saw the possibilities of profit. By 1856 Thomas North was owner of about 9,500 acres of continuous coalfield, centred on Cinderhill colliery, Basford, held from the Duke of Newcastle.

Nottinghamshire collieries and old coal pits, c.1880. Click on the image for a downloadable PDF version.

During the 1850s collieries were opened in the Langley Mill, Eastwood and Ilkeston areas. In 1854 the Duke of Newcastle began sinking two pits at Shireoaks near the Nottinghamshire border. By 1861 the main collieries near to Nottingham were Cinderhill, Newcastle, Kimberley, and Babbington, all belonging to Thomas North; Radford, Catstone Hill and the Old Engine-pit near Trowell Moor, belonging to Lord Middleton, and the Watnall Colliery. By 1860 there were 21 collieries operational in Nottinghamshire and 26 by 1869. Output reached 732,666 tons in 1862 and rose to 1,575,000 tons in 1867.

The 1870s saw no fewer than sixteen new collieries come into production, a larger number than in any other single decade. Another 25 opened 1880-1910, mostly situated along the Nottingham-Mansfield axis, except for Clifton and Gedling collieries. The results were impressive with production reaching 3.1m tons in 1854, 12m in 1880, and over 24m in 1900, when it was equivalent to more than 10% of national output. For Nottinghamshire alone output was 6,970,424 tons in 1897, 11,728,886 in 1907 and 11,028,639 tons in 1908. In 1897 23,024 men and boys were employed in the county’s collieries, rising to 35,415 in 1907.

Coal Production in the East Midlands, 1700-1900

| Year | 1700 | 1750 | 1800 | 1815 | 1830 | 1850 | 1890 | 1910 |

| Output (000s tons) | 75 | 140 | 750 | 1400 | 1700 | 3.4m | 18.5m | 31.2m |

| % UK total coal output | 2.5 | 2.8 | 5.0 | 6.3 | 5.6 | 5.1 | 10.4 | 11.7 |

Sources: M.W. Flinn, History of the British Coal Industry 1700-1830 (1984); R. Church, History of the British Coal Industry 1830-1913 (1986)

Mining families migrated into the area, sometime forming whole new communities such as Newstead Colliery Village. Until Newstead Colliery as sunk in 1873 Newstead was little more than a few scattered farms and cottages on the Newstead Abbey estate, famous for once having been the property of the poet, Lord Byron. As a result of migration, the population increased by 400% between 1871 and 1881, and the colliery owners built purpose-built housing for the men and their families.

The 20th century

Cotgrave Colliery in 1964.

The mid-Nottinghamshire reserves were exploited in the years after the First World War with the opening of the Dukeries coalfield, which stretched from the Yorkshire border to Cotgrave in south-east Nottinghamshire. This in turn led to the development of new mining villages in an area between Worksop and Mansfield, with rural villages such as Edwinstowe, Clipstone, Ollerton, Bilsthorpe and Harworth experiencing rapid growth from an invasion of miners. Ollerton, for example, grew from 676 to 3,912 between the 1921 and 1931 censuses as a result of the opening a the colliery in 1925. New collieries opened as a result of this initiative were Rufford (1915), Clipstone (1922), Blidworth (1926), Bilsthorpe (1927), and Thoresby (1928).

The coal industry was nationalised by the Labour government in 1947, but it remained a major employer in Nottinghamshire for the next four decades. By 1986 24,000 industrial workers were employed by British Coal in Nottinghamshire (excluding Manton and Shireoaks/Steetley which were in the South Yorkshire area). Production in Nottinghamshire rose from 7.46m tons at nationalisation in 1947 to a peak of 14.37m in 1963. Bevercotes, the first fully-automated colliery in the world – and Cotgrave, were both opened in the 1960s.

In the years after 1945 the coalfield was a major supplier of almost all the consumer regions in England serving the domestic and industrial needs of the London market, the south and East, South Lancashire and Cheshire. By the 1960s the picture was changing, with production moving away from the domestic market to the supply of the electricity industry. Production on the south Nottinghamshire coalfield was 8.54m tonnes in 1981-2, and the proportion acquired by the Central Electricity Generating Board was 79 per cent of output. Ratcliffe-on-Soar power station alone consumed 65 per cent of the output of mines in south Nottinghamshire.

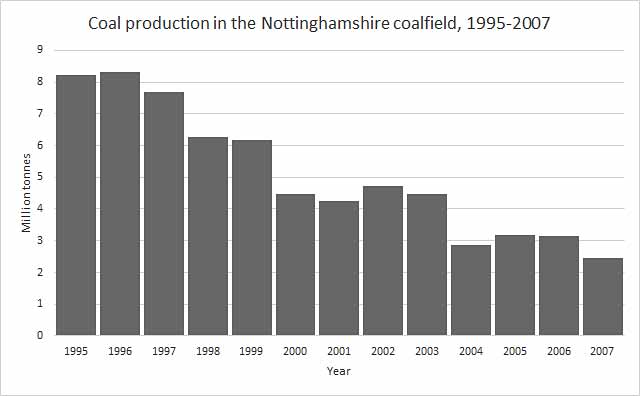

The future of the industry was increasingly called into question as workable reserves were exhausted. During the 1960s nine collieries ceased production, and by the 1970s the position of the coal industry came increasingly under threat and following strained industrial relations and periods of strike action in the mid-1970s and mid-1980s the decision was taken to reduce the number of local collieries. As a result, production in Nottinghamshire declined rapidly:

By the end of 2008 only Thoresby and Welbeck collieries remained in production. Welbeck, however, was closed in 2009 and in April 2014 UK Coal announced that it planned to close Thoresby Colliery in 2015 with the loss of over 500 jobs. The closure of Thoresby marked the end of deep-pit coal mining in Nottinghamshire.