|

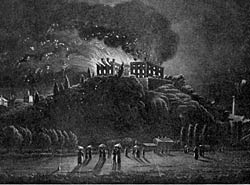

Nottingham Castle on fire, 10 October 1831. |

Nottingham gained a reputation as a centre for riotous behaviour associated with political radicalism. The town authorities were in favour of parliamentary reform from the 1780s, and this had an impact on the way elections were conducted at least until the 1880s. In addition, Nottingham was the centre of Luddite disturbances, it saw some of the worst riots in the country at the time the 1831 Reform Bill was thrown out by the House of Lords, and it was an acknowledged centre of the Chartist movement. With the passing of the Secret Ballot Act in 1872, and the end of election activity in the market place following further political reforms in the 1880s, the radical image of the town slowly faded. The Conservatives, out of power for over a century, finally triumphed on the Corporation in 1908, but Nottingham was one of the last major provincial cities to become a Labour stronghold. After amicable power sharing on the council during the inter-war years, Nottingham since the 1960s has become a Labour stronghold, both in local and parliamentary elections.

Nottingham’s political reputation was established at the 1790 Parliamentary election when the campaign was marked by violence. On 17 June all the windows of Smith’s bank, on the site of the present National Westminster branch next to the Council House, were smashed. One of the sitting members standing for re-election was Robert Smith of the banking family. According to Thomas Bailey, ‘the ground was everywhere as an entire sheet of glass’, and he claimed that the town had never seen such riots. Special constables were enrolled to restore order, and troops were called out, as a result of which one man was shot dead. This proved to be the start of frequent election disturbances, and Nottingham contests were marked by disorder over the following decades. In 1861, for example, the local diarist Samuel Collinson, wrote that ‘the town seemed to be given up to ruffianism, mobs of people were about every polling place insulting the voters for Lord Lincoln. Towards the afternoon all the shops in the Market Place, Pelham Street, Clumber Street, and Bridlesmith Gate were closed. Ruffians insulted all decent looking people, tearing their hats from their heads, pocket picking was carried on extensively, and the whole scene was a disgrace to the town and the times we live in.’ The situation was even worst in 1865 when a riot took place in the market place, the platform put up for the hustings was smashed, and the candidates’ committee rooms wrecked.

The Luddite disturbances were largely provoked by economic conditions in the hosiery trade, although they may have had political and possibly even revolutionary undertones. The first outbreak was in March 1811, and there was further trouble during the winter of 1811-12, the spring of 1814, and 1816-17. Luddism was a form of machine breaking. It broke out when some of the larger hosiery employers forced down wages to try to stimulate trade and open up new markets. Other employers looked for different, cheaper goods, which it was hoped would create new demands. To this end, some hosiers began to produced ‘cut-ups’ rather than fully-fashioned garments, and lace manufacturers started to produce single-press lace. The Luddites particularly objected to the frames producing cut-ups, although action against the wide frames on which these were produced followed, rather than accompanied, action triggered by falling wages. The framework knitters believed that they had been badly treated by the hosiers during the depression of 1811-12. One knitter claimed in 1812 that he had fed his family on barley-bread, old milk, and potatoes. The Luddites received no sympathy in Parliament, despite an appeal on their behalf in the House of Lords by the young Lord Byron. In 1812 Parliament passed legislation turning frame breaking into a capital offence.

Luddism originated in economic distress, but did it become a political movement? The Tory Nottingham Gazette suggested that the disturbances were expressions of political conflict: Jacobinism, according to the newspaper, was the root and spring of frame breaking, and so it saw Luddism as a revolutionary protest. It may have had seditious intentions, particularly in the later phases of the movement. George Coldham, the town clerk, was concerned in 1815 that law and order might be on the verge of breakdown in Nottingham, and his successor in the post, Henry Enfield, claimed in 1816 that suspicious meetings were taking place in public houses, and that there was ‘talk of revolution’ among the Luddites.

Few Luddites joined the ill-fated uprising led by Jeremiah Brandreth in 1817. He, together with a number of other local radicals, planned an uprising on 9 June 1817. Brandreth led the men of Pentrich in Derbyshire to Nottingham on the night of 9 June, promising that they would meet another 16,000 men in arms by the time they reached the town. A provisional government would be set up, and they would march on London. In Nottingham, about 100 men, rather than the promised 16,000, assembled, but dispersed peacefully. Meanwhile Brandreth and his followers were intercepted by troops near Eastwood, more than eighty were arrested, of whom fourteen were later transported and three, including Brandreth, executed.

Support for Parliamentary reform first surfaced in Nottingham politics during the 1780s, and the town remained committed to electoral reform through the following decades. In March 1831, following a public meeting in the town, more than 9,000 people signed a petition in favour of reform. When, in October 1831 the second Reform Bill was rejected in the House of Lords, the news was greeted in Nottingham with disbelief and, subsequently, a riot. There were disturbances in the town on 9 October, prior to a public meeting in the market place the following day. The crowd dispersed quietly after the meeting, except for a small group which took the law into its own hands by tracking down opponents of reform living in the town. This group first went to Colwick Hall, and subsequently returned through Nottingham to the castle. Colwick was a target because the owner, John Musters, was a known anti-reformer, while the castle was owned by the Duke of Newcastle, one of the peers who voted against reform in the crucial vote on 8 October. The castle was empty, but the crowd forced an entrance into the building, which was then gutted by fire. The following day the crowd reassembled and marched to Beeston, where a silk mill was burnt down. Three men were later tried, found guilty, and executed for their role in this event. The Nottingham riots were among the worst in the country following the rejection of the second Reform Bill, and the passing of the third bill in 1832 was suitably greeted in Nottingham where the corporation voted 150 guineas towards patriotic celebrations.

|

Fergus O'Conner (1794-1855), Chartist leader and MP for Nottingham (1847-52). |

Parliamentary reform enfranchised the middle classes but left the working man still without a vote. Chartism, the movement founded in 1837 to promote political democracy, was well supported in Nottingham. A meeting held on the Forest on 5 November 1838 was attended by about 3,000 people, and further gatherings followed in the early months of 1839. Of the 1.3 million signatures on the first Chartist petition to the House of Commons in July 1839, 17,000 were said to have come from Nottingham. The petition was rejected, and Chartism made no more progress until 1842. Feargus O’Connor, the Irishman who had become the leading light in the movement, spoke in Nottingham in February 1842, when people came on foot from all over the county. In August, there were Chartist disturbances in the town, leading to what was called the Battle of Mapperley Hills, when around 5,000 Chartists assembled on Mapperley Plains, and troops arrested 400 men. This led to a riot, but once again the movement faded. In 1847 O’Connor was elected MP for Nottingham, and the town became a leading centre of the third and final phase of Chartism, 1847-8. A third petition was presented to Parliament on 10 April 1848, but this was also rejected. In subsequent years, economic prosperity, and O’Connor’s descent into madness, saw the movement fade away.

By the 1850s, although elections still tended to be feisty affairs, there were no similar movements to Luddism or Chartism. This was partly because favourable economic conditions meant that energy once expended in such movements was channelled into trade unionism, and partly because reform acts in 1867, 1872, and 1883-5 met many of the political demands of the Chartists by extending the vote to working men, bringing in the secret ballot, and promoting equal electoral districts. Nottingham’s radicalism was tamed, and although a branch of the Independent Labour Party was well established by 1893, the willingness of Nottingham voters to return Conservatives for two of the three Parliamentary seats by the end of the century suggests that the Labour movement struggled to make political headway in the town. The corporation fell to the Conservatives in 1908, and the real breakthrough for the Labour Party was only in 1945, long after similar provincial cities such as Leeds and Sheffield.

Nottingham may have been radical, but the surrounding county was relatively quiet. The extent of radical activity in the county town may have been exaggerated because it was the venue for county and town elections, and it had a large meeting place (the market place, now Old Market Square) and a tradition of public meetings to discuss political affairs. Newark and East Retford also returned Parliamentary candidates, but although there were some scandals in elections in both towns, neither seems to have enjoyed either the radical reputation of Nottingham, or the accusations of disloyalty bordering on rebellion which stuck to the county town.

On the general theme of radical behaviour in Nottingham see John Beckett, ‘Radical Nottingham’, in John Beckett, ed., A Centenary History of Nottingham (1997), chapter 13, and Rebels, Riots and Reform, an inter-active CD-ROM (available through the County Library service).