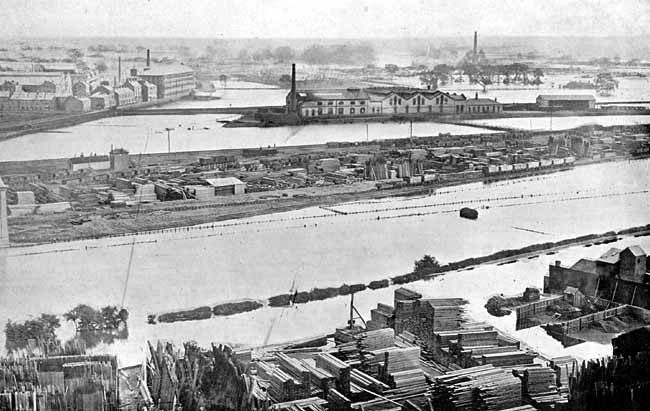

The Great Flood of 1875: view from Nottingham Castle.

Weather observing – origins

People have been observing the weather since the dawn of human awareness of their environment. Traveller, sailors and many others would naturally have kept an eye on the weather. However, recording of the weather only started seriously in the second half of the 18th century. Weather records prior to then are sparse, and are mainly confined to notes on a day’s weather in otherwise ordinary private diaries. Although useful, these usually only contain references to notably good or bad weather on specific days and do not give a long ‘run’ of information.

Meteorological instruments such as thermometers and barometers were in regular use since the middle of the 17th century. We do have temperature records going back to 1659, but some of the 17th century data are possibly a little unreliable. Monthly and annual rainfall totals for England and Wales go back to January 1766. There are earlier records known, but prior to 1766 there are gaps.

Most meteorological research and recording was carried out by gentleman amateurs. The British (later Royal) Meteorological Society was founded in 1850, with the objective of encouraging the study of the weather on a more formal basis. In 1860, following a series of around ten very dry years, George James Symons began to publish British Rainfall, an annual publication which included annual rainfall amounts from a wide variety of sources. At its peak, British Rainfall received observations from around 6,000 places. Many of the observer were amateurs. British Rainfall finally ceased publication in 1991. Rainfall data can now be obtained from the Environment Agency.

Notable weather events in Nottinghamshire

There have been many notable weather events in the county. This article relates just a few.

Tornadoes

One particularly dramatic account is of a tornado which passed over Nottingham on 1st November 1785. The previous day had been overcast with thunder at times. The 1st November was warm, with periods of heavy rain. At about 4pm, a funnel-cloud was observed near the village of West Bridgford. A funnel-cloud consists of a rapidly rotating patch of cloud which then descends in the shape of a funnel. If the funnel-cloud reaches the ground, it is usually then referred to as a tornado. The funnel-cloud moved over the river Trent towards the village of Sneinton, where it did considerable damage to houses, barns and trees. Fortunately, Green’s windmill had not at that time been built!

On 29th June 1848 a tornado did considerable damage in the village of Winkburn, near Newark.

In more recent times, tornadoes have been observed at Grantham and Newark in 1977, at Gotham in 1984; at Annesley in 1985 and on Christmas Day, 1990, at Keyworth.

Severe snowstorms

On 1st February 1772, there was a severe snowstorm over Nottinghamshire. Several people perished from cold on their way back from Nottingham Market. In 1776 there was a further report of people being frozen to death on the Mansfield Road between Redhill and the Seven Mile House.

Thunderstorms and lightning strikes

House in Whatton hit by lightning in March 1904.

Numerous accounts can be found. During a severe thunderstorm in March 1904, a house in Whatton was struck by lightning and wrecked.

On Sunday 4th July 1915, a severe thunderstorm crossed Nottinghamshire. The tower of the church at Bunny was struck by lightning whilst a bible class was being held. The young people at the class were terrified but fortunately unhurt.

In July 1975, a severe storm caused much damage at Welbeck Colliery. After the storm, hailstones up to two inches in diameter were found.

Weather Observers and Recorders in Nottingham

Walkeringham Rectory records

One of the most useful early records is that kept in a bound book by the Reverend J.K. Miller, Rector of Walkeringham in north Nottinghamshire. Rev. Miller kept a barometer and a thermometer, the latter on the outside north wall of his rectory where it would not be affected by the sun. He recorded the temperature and air pressure every day at 7am, 2pm and 9pm, from 1826 to 1855. He also kept very detailed notes of the weather on each day.

Records at Bromley House 1826. The end of the Little Ice Age

Bromley House on Angel Row in Nottingham was built in 1752 as a private residence for a prominent family of bankers. In 1816 the Nottingham Subscription Library was formed, in rented premises at Carlton Street, but the Library purchased the freehold of Bromley House in 1821 when the house became available. The early members of the Library were very interested in scientific matters, including meteorology. A remote-indicating wind-vane was installed in 1821, in the early days of the Library. The wind-vane was restored in 2000 and is now in good working order. Other scientific instruments noted in the records are terrestrial and celestial globes (sold in the early 20th century) and two mercury barometers. Both barometers are still at Bromley House. The older of the two instruments was restored recently and now gives accurate readings of the atmospheric pressure. The library holds a number of historic documents, one of which is a record of the weather for the year 1826 and for January and February 1827, made at the house. It is most likely that the record was kept by James Archer, who was appointed Librarian in 1821. Mr. Archer was allowed by the Library Board to take leave of absence of two to three weeks in each of the years 1826, 1828 and 1829. In 1826, he went to Scotland, and there is a gap in the weather record from 9th September to 6th October of that year which presumably corresponds to his trip to Scotland.

The document contains observations recorded in a printed booklet of page size 365mm x 230mm, with introductory information and hints on keeping the records. There are then twelve pages, one for each month, for observations. Measurements and comments were noted at the hours of 8am, 2pm and 8pm, for each of which there are columns for barometer, thermometer and weather, then a column for rainfall and finally a column for general comments. The records were entered in manuscript in the printed columns.

The Bromley House record covers January to December 1826, but inside the back cover are records for January 1827 and for 1st to 13th February 1827. Each day’s record has, for the three observing hours (8am, 2pm, 8pm) a column for barometric pressure, temperature and a note on the weather, usually as a single word such as fine, cloudy, raining, showery &c. Rainfall is very occasionally recorded, but there is no consistent rainfall record. This is surprising, as rainfall is one of the easiest meteorological parameters to measure. The record has been kept assiduously, with no gaps other than the period of James Archer’s vacation in Scotland.

In the early part of the 19th century, Britain was still in the grip of the Little Ice Age. The winter of 1826 was very cold; ice was recorded on the Thames. That of 1827 was almost as severe. The monthly agricultural report in the Nottingham Journal of 4th February 1826 stated that ‘the late frosts in January had put an entire stop to all field operations’. However, ‘The early part of February was tolerably dry, serene and mild, with some gentle frosts at night. There were heavy rains later in the month. Lambing was later than usual’ (Nottingham Journal 11th March 1826). The summer of 1826 was noted for a great drought; June, July and August were persistently very warm. The average temperature for those three months was 17.60C according to the Central England Temperature series, which began in 1659. The period mid-June to mid-July had a mean daily temperature of 19.70C. The summer was also notably dry. The England and Wales Precipitation series showed that the average rainfall in England and Wales in June 1826 was 12.4mm, making it one of the driest Junes on record. The total rainfall for the year 1826 was 122mm, which is well below average. The Nottingham Date Book records that in July 1826, ‘An extremely protracted drought so lowered the Trent, that no person living could remember the water so low before. Advantage was taken of the circumstance to examine and reconsolidate the bridge. One of the piers on the eastern side was entirely rebuilt and the others were repaired’.

The warm summer is corroborated by the records made by the Rev. Miller at Walkeringham in North Nottinghamshire, who notes on 18th July 1826, ‘First wheat cut in Mr. Belton’s field’ and from 23rd to 29th July, ‘Harvest general this week, principally wheat’. There were thunderstorms at Walkeringham on 31st July and 1st August, and on 8th August a temperature of ‘very nearly 79 out of doors, in shade on the N. side of the [illegible, presumably Rectory]’

Weather on 10th October 1831 – the sack of Colwick Hall and burning of Nottingham Castle

In October 1831 opposition to the passage of the Great Reform Bill occasioned serious rioting in Nottingham and, amidst other damage, the rioters set fire to Nottingham Castle. Heavy rain in the evening of 10th October did not douse the flames and the castle was gutted.

Edward J Lowe (1825-1900) of Highfield House

The Lowe family were wealthy landowners in Nottinghamshire. Alfred Lowe, father of Edward, was a member of many national and local learned societies. Alfred was especially interested in meteorology and astronomy, and Edward inherited these interests. In 1840, at the age of 15, Edward began to make weather observation and keep records at his home, Highfield House (now on the campus of the University of Nottingham). He wrote prolifically, his first paper being ‘A Treatise on Atmospheric Phenomena’ in 1846. In 1852 he published a book ‘The Climate of Nottinghamshire’ and in 1853 ‘The Conchology of Nottinghamshire’ as a result of his collecting of the shells of molluscs around the county. Edward built Broadgate House in Beeston with an observatory on the roof. As a result, his observations formed part of the regular weather reports in the Times newspaper.

The Royal Meteorological Society

On 3rd April 1850, a meeting of ten gentlemen interested in meteorology took place in the Library of Hartwell House in Buckinghamshire, the home of Dr John Lee, a well-known patron of astronomy and meteorology. Amongst their number was Edward J. Lowe of Nottingham. The meeting agreed to set up a British Meteorological Society to advance the science of meteorology. The Society quickly grew and by the end of the first year of its existence had almost 100 members. In 1886 Her Majesty Queen Victoria graciously bestowed the title of ‘Royal’ on the Society, which is now the Royal Meteorological Society. Amongst the early members were Lady Anne Isabella (Annabella) Noel Byron (1792-1860), the widow of the 6th Lord Byron (1788-1824), the rebellious English poet, and their daughter, Augusta Ada, who was born in 1815. Ada married William King in 1835, becoming the Countess of Lovelace in 1838 when her husband became the first Earl of Lovelace. Lady Byron, an able mathematician, encouraged her daughter to study mathematics and science. In 1833 Ada met Charles Babbage (1792-1871), the celebrated mathematician and pioneer of machine computing, and subsequently worked with him for many years. Ada can be regarded as the first computer programmer. Babbage’s ‘Calculating Engine’ is in the Science Museum, London.

William Tillery, Welbeck Abbey

Mr Tillery was the head gardener at Welbeck Abbey for many years. He came from Scotland and is recorded as aged 30 and living at Welbeck with his family in the 1841 census. He stayed at Welbeck until about 1873. He recorded the rainfall at Welbeck from 1837 until November 1872 and his records were included in British Rainfall from the first issue in 1860.

John Deverill Walker

John Deverill Walker was born in 1857, the son of Thomas Walker. For many years, the Walker family owned the Forge Mill at Mill Lane near Hucknall. The mill is one of a number built at Papplewick, Hucknall and Bulwell by the Robinson family who pioneered industrial cotton spinning and the use of steam power in Nottinghamshire. The Walker family used the mill to crush bones for fertiliser. The Forge Mill is now a Grade II listed building. Because the mill was water-powered, it was vulnerable to variations in the flow of water along the river Leen. Drought, and particularly floods, were of concern. John Deverill instituted the daily measurement of rainfall at the mill in about 1880, and from 1881 to 1922 he contributed his rainfall readings to British Rainfall. He retired to Ruddington and continued recording the rainfall there until his death in January 1947 at the age of 91. His record of seventy-five years as a rainfall recorder in British Rainfall has not been equalled.

Henry Mellish of Hodsock Priory

Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Mellish, CB, DL, JP, FRGS was born in 1856, the son of Lt Col William Leigh Mellish and his wife Margaret, daughter of Sir Samuel Cunard, who founded the Cunard shipping line. Educated at Eton and Balliol, Oxford, he was called to the Bar in 1882, elected a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society in 1902, and appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath in 1917. An excellent rifle shot, he set up an experimental rifle range at the family home, Hodsock Priory. From his studies, the Hodsock Ballistic Tables for Rifles was published in 1925 by FW Jones, with a preface contributed by Henry. He was fascinated by meteorology and kept detailed weather records at Hodsock for almost fifty years. Many of his observations were published. He was elected President of the Royal Meteorological Society for the years 1909 to 1911. Henry died in 1927. He was unmarried, and Hodsock passed to the Buchanan family, who were descendants of his grandfather Edward Mellish, sometime Dean of Hereford Cathedral.

Arnold Birkbeck Tinn (1891-1962)

Arnold Tinn was the son of the Rev Christopher Tinn and his wife Margaret. Rev. Tinn was a Primitive Methodist minister, and the family moved around the country at regular intervals. A move to Ramsay, Isle of Man, when Arnold was seven years old inspired his life-long interest in meteorology. Eventually, the family moved to Huddersfield where Arnold, at the age of seventeen, caught tuberculosis. He remained a semi-invalid all his life, but this did not diminish his interest in meteorology. The family moved to Nottingham in 1915. Arnold kept daily records of the weather, first at Burford Road in Forest Fields, and from 1935 at Calstock Road, Woodthorpe. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Meteorological Society in 1926.

During the Second World War he developed a firm friendship with Professor K.C. Edwards at the University of Nottingham. They corresponded regularly and most of the correspondence is included in the papers of Professor Edwards held in the University of Nottingham Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections.

Arnold wrote numerous papers on the weather and related topics, and a book ‘This Weather of Ours’ which ran to two editions. He was a regular contributor of weather notes to the Nottingham Evening Post. Arnold died in 1962 and is buried with his parents in Redhill Cemetery, Nottingham. His weather records, particularly those from 1935 to 1961, are amongst the most detailed we have for the City of Nottingham.

Nottingham Castle as the official Nottingham weather site

From 1876 to 1983, Nottingham Castle was an official meteorological observing site. Instruments were mounted on the roof, and daily readings taken. All the records are in the National Meteorological Library and Archive, Exeter. In 1983, the Nottingham meteorological site moved to the Watnall Weather Centre, which is outside the City boundary. The highest temperature ever recorded at the Nottingham Castle site was 94.60F (34.80C) on 9th August 1911.

Rainfall recording – long term records

George James Symons (1838-1900), at the age of 17, was one of the founder members of the British (later, Royal,) Meteorological Society. He was appointed by Admiral Robert Fitzroy to the newly formed Meteorological Department of the Board of Trade (the future Met Office) in 1860.

During the 1850s there was a severe drought in England which prompted George to set up the British Rainfall Organisation. He contacted as many people as he could find who kept rainfall records. The records eventually were published in the annual British Rainfall, a volume which only ceased publication in 1991 with the advent of computerised records.

Nottingham Weather Centre, Watnall

Nottingham Weather Centre started life in Spring 1940 as the H/Q no 12 Group RAF Fighter Command, as an underground control room. There was also a meteorological observation station above ground. After WW2, and during the Cold War, Watnall was used as a ROTOR station to plot incoming Russian bombers, should war break out with the then Soviet Union. The station closed in 1961 and the meteorological station at ground level became the Nottingham Weather Centre, which still functions as the official recording site for Nottingham.