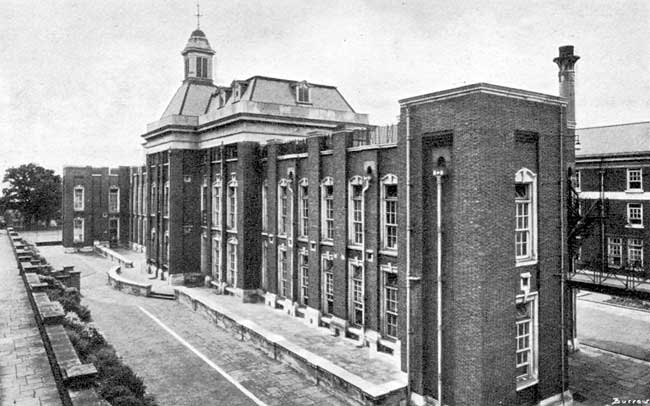

The Children’s Hospital, Nottingham

The Children's Hospital in the 1930s.

The year 1869 saw the formation in Nottingham of the first Children’s hospital. It was also the year of the Great Sanitary Commission which had looked into living conditions and health in Britain. Once again the standard of living of the poor was beginning to cause concern to the more enlightened of society. The housing of the poor in Nottingham was constantly criticised and many of the houses were nothing better than hovels where disease was rife. Childhood diseases, such as measles, whooping cough and scarlet fever killed many children in their first five years. Infant mortality killed many babies before their first birthday and those who survived into the later years were affected by diseases affecting their lungs, bones and sight.

This growing concern for the children living in these conditions was brought before the General Hospital Committee who in a short space of time had gathered support for a scheme to begin helping sick children. A committee was formed with the Reverend J C Willoughby as Chairman and Miss Hine, daughter of the architect T C Hine, became sister in charge of the new hospital, which was named as the Hospital for Sick Children and House of Charity. The first obstacle was to find a suitable building which after the third attempt was to be Russell House at 3 Postern Street, Nottingham at a cost of £1500. The owner of the property, Alderman Knight, gave £500 towards it and another £450 was provided from hospital funds, the remainder came from voluntary donations.

Despite its good intentions there was an air of sanctimony about its inception with Rev Willoughby commenting on the life of a woman who had given birth to 13 children, ten of whom had died, “There is a need for an institution to instruct the lower classes as to the effects of overcrowding, dirt, drunkenness and improper food.”

The aims of the hospital were to 1). To provide for the reception, maintenance and medical treatment of the children of the poor, from any distance, under ten years of age during sickness, and to furnish with medicine and advice those who cannot be admitted into the Hospital, as far as the means of the Institution will allow. 2). to obtain and diffuse a better acquaintance with the management of children during sickness and 3). To assist in the training of women in the special duties of children’s Nurses.

The hospital was opened on 1 July 1869 for eight in-patients and by the end of the year 80 patients had been admitted at an average cost of 4/6 per week. Parents who sought admission for their child had to sign a declaration that they were in poverty. Other poor children could obtain help but had to pay a small amount. The Nottingham Charity Organisation Society referred many children to the hospital. Like the beginnings of Harlow Wood, many children who were sick with diseases such as rickets, hip-joint or scrofulous diseases were refused admission because they needed to rest for many months or were in need of a good diet and fresh air. To offer such children a bed would be to convert the hospital into an asylum rather than a place of treatment. The hospital also treated out-patients, initially only one day a week and then later two days a week.

During the next ten years the hospital provided a necessary service but with the constraints of lack of space, money and quibbling over where the money came from and the necessity to build the hospital in the midst of a popular neighbourhood! This was further antagonised by the upper age for admission being raised to 12 years. There seemed to be a constant fear of the hospital being ‘used’ by parents, however with the help of the Charity Organisation Society the undeserving cases were filtered out. It would seem that life in the hospital for the 30 children was something completely different to their normal lives. A newspaper described Christmas on the wards with Christmas stockings, a visit from Santa Claus, presents and turkey for dinner! The Children’s Hospital was one of the few buildings in Nottingham to have a telephone installed. This enabled contacting the medical staff at the General Hospital much quicker.

In 1887 a new out-patients department was opened at a cost of £1000 which enabled over 2000 out-patients to attend. As well as the medical staff required to run the hospital the hospital relied on outside charity help, which included the Cot Fund (1881) initiated by the Nottingham Girls’ High School to help maintain beds. Local dignitaries also contributed, such as Colonel Charles Seely, who let children convalesce in his own home and a Mr Heslop who sent his carriage to take children out for rides.

The success of the hospital was its own enemy because by the last decade of the nineteenth century demands on the hospital’s resources outstripped the funds and there came a point where the hospital had to refuse deserving cases. By 1898 the space of 32 cots was just not sufficient to cope with growing number of needy cases.

Fortune shone down on the hospital as Thomas Birkin, lace manufacturer, heard of the plight and donated his home, Forest House, for their immediate use. The cost of converting the house into a hospital amounted to £8000. It was fitted with two main wards and was officially opened in 1900 by the Duchess of Portland, who was also greatly involved with the Orthopaedic hospital at Harlow Wood. In 1901 ‘The Grand Bazaar’ took place in November to raise funds for the hospital with Field Marshall Earl Roberts unveiling a memorial plaque commemorating Thomas Birkin’s generosity. Over £4000 was raised, which was no mean effort. The hospital was fortunate to attract the wealthy of Nottingham and with Birkin’s death in 1923, John Player and his wife offered to pay and equip a new wing at a cost of between £30000 and £40000. Thomas Birkin had stipulated that the house should not be altered during his lifetime so when John Player made his donation the house was extended and brought up to date and increased the bed capacity to 80. The new wing was opened by Princess Mary in April 1927.

The hospital continued to help as many children as possible throughout the 1930s and 1940s and after the Second World War the introduction of the National Health Service saw a radical change in how hospitals were run and managed; medical progress had reached the point where, without finances, it could not develop. The introduction of the National Health Service in 1946 meant just what the doctor ordered – more financial support and medical intervention. So it was that the Children's Hospital became administered by the Sheffield Regional Hospital Board and the Nottingham No. 2 Management Committee. The Children’s Hospital was now free and open to the poor and the rich.

And so the Children’s Hospital continued to treat the youngest members of society for another thirty years. Whereas at the inception of the hospital the patients were suffering from diseases and injuries which were untreatable at the time, today the vast majority of patients are admitted through ‘accidents’ which are now treatable. In 1978 a quarter of children admitted were from a similar background of poverty and social deprivation to those first admitted in 1869.

In 1977 along with many other departments the children’s hospital came under the umbrella of the University Hospital at the Queens Medical Centre. It is interesting to note that at the very outset of the Children’s Hospital the fear was of separating the child from its mother. Dr George Armstrong, founder of the first children's dispensary in Red Lion Square, London in 1769, had warned: "If you take away a sick child from its parents or nurse you will break its heart immediately." Today the acceptance and adoption of the new concepts in childcare of the Platt Report on the Welfare of Children recommendations have improved the conditions for the child but also his likelihood of a better recovery. Children in hospital need not necessarily be confined to bed, that special amenities for recreation and education should be available and that visiting should be unrestricted. One of the main philosophies behind this report was that the child "should be subjected to the least possible disturbance of the routines to which he is accustomed." When the Children’s Hospital transferred to the University Hospital the provision for parent accommodation, so they could be with their child whilst they were in hospital was something only the earlier generations of healthcare specialists could have dreamt of.