Overview: 1660-1800

Newdigate House, Castle Gate, was built 1675-80.

From the mid-seventeenth century Nottingham was one of many provincial towns to enjoy a period of urban renewal, which witnessed a transformation of the town's housing, and a major refurbishment of the streets and public buildings. Members of local gentry families began moving into the town. They built substantial houses, some of which can still be seen on Low Pavement and Castle Gate. These new houses were designed in the latest architectural fashion and built of locally made brick.

Few of the seventeenth century houses have survived, although a handful can be seen at the top of Castle Gate, notably Newdigate House. A stimulus to the development of this fashionable residential area was provided by the Duke of Newcastle. He acquired and rebuilt or, more accurately, replaced the castle. The new building continued to be referred to as Nottingham castle, but it can best be described as a ducal palace, inspired as much by Continental baroque as by English styles.

Inside these houses, a revolution in consumer spending was reflected in a range of new furnishings. The ‘middling sorts' who we associate with late seventeenth and early eighteenth century town houses were able to afford mirrors and china ware, books and other luxury artefacts on a scale previously unknown.

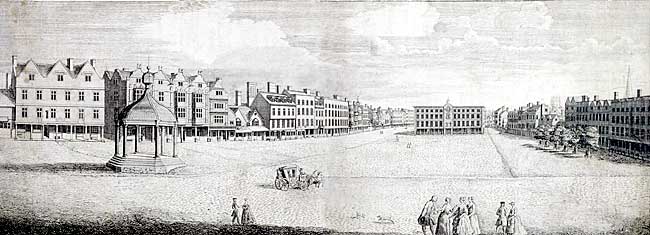

These people also took an interest in the townscape. Public buildings such as the Guildhall were restored or replaced, and new buildings erected, including the Bluecoat School, the Exchange (replaced in 1929 by the current Council House), Collin's almshouses, and the St Mary's Gate theatre.

Attention was also paid to the quality of life in the town, with improvements to the water supply and new regulations for cleaning the increasingly busy streets as greater affluence was reflected in the number of coaches, carriages, chaises and chairs. Chapel Bar, the last surviving medieval gate, was demolished in 1743 to ease traffic flow and several of the narrow medieval streets were widened.

New leisure pursuits particularly suited to the tastes of the emerging middle classes included bowling greens, assembly rooms, the race course on the Forest, plays and concerts. As a result, by the mid-eighteenth century Nottingham was a fashionable town.

Thomas Sandby's view of the Market Place from Beastmarket Hill looking towards the Exchange (1740). (© Nottingham City Museums and Galleries; Nottingham Castle).

This optimistic picture of Nottingham has to be tempered by some other changes which were rather less pleasant. Badder and Peat's map of 1744 shows a garden town with many open spaces, but the surrounding open fields limited the potential for development. As a result it was not possible to develop a new town with public buildings and public spaces in the form of planned promenades, crescents and squares as in Bath, York, Edinburgh and elsewhere.

By 1700 Nottingham's population had reached 6,000, but it grew rapidly in the following fifty years to reach 11,000 by 1750. Not surprisingly there were objections to newcomers settling locally. Traders feared possible threats to their position, while the corporation worried about a likely increase in the numbers of the poor.

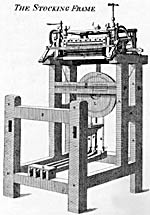

The major attraction for migrants was the hosiery industry which by 1750 was rapidly turning Nottingham into a prosperous industrial centre. During the course of the seventeenth century established industries such as clothmaking, tanning and ironworking went into decline. By contrast, hosiery, or knitted fabrics, grew rapidly. Wool was woven and knitted in the town from at least the sixteenth century, and silk stockings were being made from about 1640.

The stocking frame.

But it was from the 1690s that the hosiery trade boomed, and the following decades brought great prosperity. Charles Deering, Nottingham's first historian, estimated in 1739 that there were 1,200 stocking knitting frames in the town, and in 1754 one-third of the town's burgesses were hosiers. The industry was supported by the local banking network, particularly Smiths Bank in the market place.

Other expanding trades in the early eighteenth century included white lead manufacture (for high quality white paint used on many country houses of the period), glass making and pottery manufacture. These were manufactures aimed predominantly at a quality market, another reflection of the boom in consumer spending among the rising middle classes.

By the later eighteenth century Nottingham was a fashionable, elegant

town: as Robert Sanders enthused in 1772 ‘the situation is not exceeded

by any in