Overview: the 19th century

King Street, with its distinctive buildings by Watson Fothergill, was created in the 1880s after clearing the infamous slums in the Rookeries

The development of hosiery manufacture from the later years of the seventeenth century gave Nottingham a manufacturing base. If urban renewal transformed the town between 1660 and 1750, textile manufacturing had no less an influence over the following century, not simply on the economy but on the town more generally.

By 1750 the hosiery industry already had a mature organisation with a well developed marketing system which operated through the City of London. Subsequently, as firms expanded and employed increasing numbers of knitters the independent framework knitter was rapidly sidelined, but changes in fashion and technical developments brought unprecedented prosperity. By 1812 there were 2,600 stocking frames in Nottingham. Two pioneers of mechanised cotton spinning also settled in Nottingham: Richard Arkwright in 1768, and James Hargreaves in 1769. Their lead was quickly taken up by other entrepreneurs, but in the longer term Nottingham did not become a major centre of cotton and worsted spinning. By 1833 the town had only four small cotton mills in production.

The impact of hosiery was astonishing. The town grew from about 11,000 people in 1750 to around 29,000 by the end of the century, and to 50,000 by 1831. Much of this growth was a result of migration as individuals and families travelled to Nottingham in search of work in the expanding textile trades. They needed to live somewhere and the building trades flourished, particularly from the 1780s. Many of the new properties were erected quickly and built cheaply on cramped sites. In the absence of effective controls they often lacked adequate sewage and waste disposal facilities. The town rapidly became crowded, and the middle classes started to vacate their fine houses in the centre in favour of newly built quality properties on the west side of the town. By the early years of the nineteenth century visitors no longer went into raptures about Nottingham, and nor is this surprising: population had tripled in sixty years without any appreciable expansion of the built-up area. The result was congestion.

From about 1810 the hosiery industry ran into trouble, and a long-term fall in demand was partly a result of changes in fashion as men began to prefer trousers to stockings. Around 1816 hosiery slipped into a deep depression which lasted until the middle of the century. This had serious repercussions for the Nottingham economy, but fortunately the decline of hosiery was offset by the rise of lace manufacture. In its machine-made form lace making evolved directly out of hosiery, considerably boosted by the technical work of John Heathcoat, who invented the bobbin net machine in 1808-9. Further major technical developments occurred in the early 1820s following the invention of the Levers machine.

During the so-call twist net fever of 1822-5 work was plentiful, population grew rapidly, and houses were built on every available piece of land until Nottingham became so overcrowded that many of those who worked in the lace industry moved into the villages just beyond the town boundaries.

In the later eighteenth century there had been some migration into villages along the River Leen (mainly Basford and Bulwell) but following enclosure acts in the 1790s New Radford, New Lenton and New Sneinton sprang up - in each case areas of industrial development between the town boundary and the existing ‘old' village cores. In addition, entirely new settlements developed at Carrington and Hyson Green. The first lace factories were built in the 1820s in New Basford.

The downside to these developments was that the framework knitters were left to crowd together within the old town. William Booth, founder of the Salvation Army, was born in Sneinton. He later recalled that his mission to the poor had been inspired by ‘the degradation and helpless misery of the poor stockingers of my native town wandering gaunt and hunger-stricken through the streets'. In these conditions epidemic disease flourished, and 330 people died in Nottingham during the 1832 nationwide outbreak of cholera.

Overcrowding partly reflected the impotence of the corporation when it came to governing a rapidly growing and industrialising town. It refused in the 1780s to contemplate enclosure of the open fields and meadows. Consequently little fresh land was made available for house building, and the price of what was available soared.

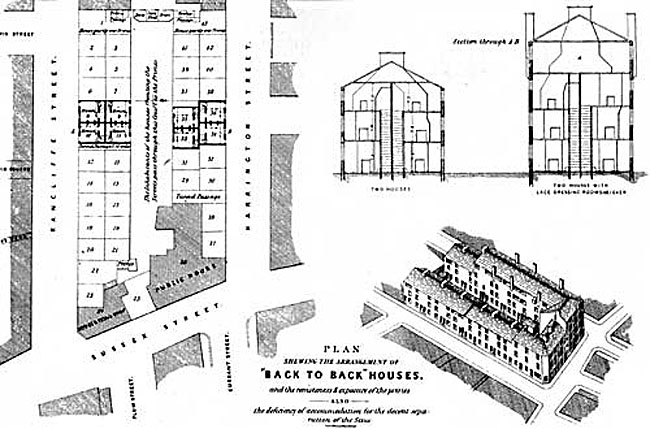

Thomas Hawksley's "Plan shewing the arrangement of 'Back to Back' houses and the remoteness and exposure of the privies, also the deficiency of accommodation for the decent separation of the Sexes" dates from 1845 and reveals the cramped conditions in the Broad Marsh area of the town.

Nottingham gradually acquired a tangled web of narrow courts, streets and alleys, poor quality housing often lacking basic facilities, and spiralling death rates. By the 1840s it had some claims to be one of the worst slums in the country.

In 1835 the Municipal Corporations Act swept away the old corporation and replaced it with a more democratically elected town council. Unfortunately the new corporation had few actual powers, and pressure for change within the town came from outsiders, particularly the early railway promoters. Space had to be found for the line, the station, and sidings. After much debate, land in the Meadows was made available to the Midland Railway Company.

This development did nothing for Nottingham's social and environmental problems, and little progress could be made during the trade depressions of the years 1836-42 as thousands of unemployed hosiery and lace workers were forced to seek temporary refuge in the workhouse. The efforts of William Felkin, one of the town's first reformers, drew little sympathy from a sceptical corporation which believed that the problems had been exaggerated.

Things changed in 1844 when Thomas Hawksley, the town's water engineer, gave evidence to a government Royal Commission in which he showed without any room for doubt that the conditions in which many textile workers were having to live had produced intolerably high death rates.

Hawksley placed the blame squarely on the shoulders of the corporation and all of those who supported retaining the open fields. His evidence was reproduced verbatim in the Nottingham Review and, as a direct result, the enclosure issue was brought back on to the local political agenda. After six months of acrimonious debate, legislation was passed in June 1845 authorizing the enclosure of the open fields and meadows surrounding the town.

Between 1831 and 1851 the population of Nottingham increased by only 14 per cent, but during the 1850s the combination of an upturn in the local economy and the release for housing and factory development of land previously in the open fields brought rapid change. The 1850s saw a 30 per cent increase in population.

The magnificent lace warehouse of Thomas Adams & Co, Stoney Street, was designed by the architect, T C Hine.

Perhaps the most significant development of the mid-nineteenth century was the growth of the area we now know as the Lace Market. The last open spaces left within the town boundaries, were gradually overbuilt with warehouses as this became a focal point of the national and international lace market. Nottingham's ascendancy in the marketing of lace was part of a long process in which the machine made product gradually usurped hand made lace. T.C. Hine designed several of the new warehouses in this area, which provided a great deal of work in finishing and marketing.

The enclosure did little for the existing poor areas of the town. The corporation appointed a Sanitary Committee to deal with ‘nuisances'. The committee had some success, but the real turning point for Nottingham came with the appointment of Marriott Ogle Tarbotton as borough surveyor in 1859, and Edward Seaton as the first Medical Officer of Health in 1872. The two men produced a report on the sanitary state of the town's housing stock, and they promoted a comprehensive Improvement Act in 1874. Under their guiding hand, in subsequent years the corporation bought the gas works in 1874 and the waterworks in 1880, the same year that the Stoke Bardolph sewage works opened. Tarbotton designed the new Trent Bridge in 1871. Following the 1875 Artizan's Dwelling Act Seaton began planning measures to improve the housing stock.

Water supply and sewage disposal problems (notably those affecting the River Leen) were a major factor in bringing about the borough extension of 1877. The town boundaries were extended to create a greatly enlarged borough which included the parishes of Basford, Bulwell, Lenton, Radford and Sneinton. A network of new roads (Gregory, Radford, Lenton and Castle boulevards) helped to knit the town together, while a developing tramway service (acquired by the corporation in 1897) enabled people to travel further for work purposes.

Lace and hosiery factories tended to be scattered about the town rather than concentrated into particular areas or zones.

Further house building saw the rapid development of Hyson Green and Forest Fields, parts of Radford and Lenton, and also Basford and Sherwood.

The corporation had lacked the imagination to adopt a scheme proposed by T.C. Hine in 1857 to transform the market place and the eighteenth century Exchange building, but following the borough extension a new Guildhall was built in the 1880s. Sadly, it lacked the grandeur of similar buildings in other provincial industrial towns.

New industrial interests also began to grow in and around the town. During the 1870s coal mining started at Clifton, and in the 1880s bicycle, tobacco, and pharmaceutical manufacturing, all came to prominence.

The corporation was persuaded by Seaton in 1881 to agree to a clearance scheme for the Rookeries, a slum area between Long Row and Parliament Street. King and Queen Streets were laid out in the subsequent redevelopment, but the project cost so much that the corporation refused to take further initiatives.

Victoria Station was opened in 1900 and demolished in the late 1960s to make way for the Victoria shopping centre. The clock tower and nearby hotel survived.

Until the 1890s the railway network made little impact on the town because the Midland Railway's three (successive) stations were all built on land released by the enclosure commissioners, and the lines ran around the outside of the built-up area. This all changed when the Great Central line was constructed through the heart of the town and its northern approaches. The new Victoria Station was built on a site of slum housing and opened in 1900. As with Seaton's Rookeries scheme in the 1880s, the fate of the families evicted to make way for the station and its approaches is less clear.

For their part, the middle classes had gradually vacated the centre of the town from the 1790s onwards, initially creating an enclave around the Ropewalk, and from the 1840s the Wellington Circus. Subsequently the middle classes also found a home in the Park and, towards the end of the nineteenth century, in Mapperley Park.

The physical expansion of Nottingham had many other implications for the use of space. Churches, chapels and schools were built in profusion, particularly after the Enclosure Act made available suitable plots of land. The nonconformists reacted quickly to the opportunities offered by industrialization, but it was the evangelical revival which inspired the Church of England to start building churches in new working class areas. Both Anglicans and nonconformists began Sunday Schools, and from the early years of the nineteenth century they moved into week day education.

Surveys in 1833 and 1851 showed just how fast they were needing to run to provide school places for children and pews for church and chapel goers. In particular, results from the 1851 survey stimulated a major church, chapel and school building programme in the second half of the nineteenth century.

A further survey in 1881 revealed that both churches and schools were seriously underprovided in the suburbs incorporated in 1877. The result was a flurry of mission churches and missioners, and a movement into social activities through semi-military movements such as the Boys Brigade. While fighting hard to keep up membership, the churches could not meet the educational challenge which passed after 1870 increasingly into the hands of the new School Board.

Pressure on space also affected leisure. Most middle class activities took place in discrete buildings such as the Assembly Rooms on Low Pavement, Bromley House Library on Beastmarket Hill and, from 1865, the new Theatre Royal. By contrast, the working classes were gradually squeezed for space, especially after the Meadows were enclosed in the 1850s. Racing and cricket took place on the Forest, but other games and interests were centred around the ubiquitous public house, and the allotment.

After 1850 new facilities were provided by the corporation including libraries, swimming pools and the Arboretum. Sport became popular in the second half of the century, including organized activities such as football and cricket (which had transferred from the Forest to the new ground at Trent Bridge in the 1830s), and cycling in the 1880s and 1890s. Towards the end of the century music hall grew out of the public house. Goose Fair, although shortened in the 1870s, remained popular, but increasingly as a social rather than as a business occasion.

By 1914 Nottingham was physically much larger than it had been in 1750, and a town of 11,000 had been transformed into a city of a quarter of a million people. Problem spots remained, particularly the working class housing in the inner core of the city, but many of the older streets had been widened to accommodate increasing traffic. The corporation took the lead in promoting electricity, and the market place was lit by electric lights for the first time in 1895. A wider range and better quality of food supply (including the first fish and chip shops) was helping to improve nutritional standards.

Better medical care was available as the General Hospital, opened in the 1780s, was supplemented towards the end of the nineteenth century by specialist institutions for women, children, and those with disabilities.

By the end of the nineteenth century Nottingham was thriving. The City Charter, granted in 1897, seemed to symbolise its prosperity. The Nottingham Daily Guardian, looking back over the nineteenth century in an article published on 1 January 1901, had no doubt that the new city had come a long way: it had been ‘a century of progress and development, such as no previous era can in the faintest degree be compared with'.