Structual

The Ducal mansion of Nottingham Castle was built in the late 17th century and extensively restored in the 1890s.

There is a huge amount of written material on Nottingham. The most comprehensive guide is Michael Brook, A Nottinghamshire Bibliography: publications on Nottinghamshire history before 1998, Thoroton Society Record Series, 42 (2002). Copies are available in local studies libraries throughout the county. Relevant pages of this are indicated as Brook, Bibliography, xxx-xxx. The fullest recent history of the city, covering all periods and topics, and also available in libraries throughout Nottingham, is John Beckett, ed., A Centenary History of Nottingham (1997).

The most important items on particular topics are detailed below.

Topography

Nottingham was physically quite small until the nineteenth century, bounded to the west by Chapel Bar, to the north by the junction of what is now Parliament Street and Milton Street, to the east by the site of the Ice Centre, and to the south by the River Leen, now Canal Street. For its physical development see

- M.W. Barley & F.I. Straw, ‘Nottingham’, in M.D. Lobel, Historic Plans I (1969)

- F.I. Straw, ‘An Analysis of the Town Plan of Nottingham: a Study in Historical Geography’, (University of Nottingham, MA, 1967)

- Trevor Foulds, ‘”A Garden called Paradise”: Variant Street Names and the Changing Townscape in later Medieval Nottingham’, Transactions of the Thoroton Society, 101 (1997), 99-108

- D.C. Large, ‘Nottingham: its urban pattern’, East Midland Geographer, 1 (1956)

Standing Buildings

Nottingham has been redeveloped at various times during the 20th century, and it has relatively few historic buildings for a town of its size.

An informed overview of the buildings of Nottingham can be found in

- Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England: Nottinghamshire (2nd edn., rev by Elizabeth Williamson, 1979)

- Elain Harwood, Pevsner Architectural Guides: Nottingham, Yale University Press, 2008

General guides to the town’s buildings and architecture can be found in:

- Barley, M. W. and Cullen, R. Nottingham Now. Nottingham Civic Soc., 1975.

- Oldfield, G. The Changing Face of Nottingham in Old Photographs. [West Bridgford], Nottinghamshire County Council, Leisure Services/Stroud, Alan Sutton Publishing, 1994.

St Nicholas' church was rebuilt in brick after being severely damaged during the siege of the town and castle during the English Civil War.

There are two medieval churches, of which the largest, St Mary’s, was extensively rebuilt in the 18th and 19th centuries. St Peter’s is more modest, in the style of a village church, where St Mary’s has cathedral-like proportions. St Nicholas’s, a medieval church in origin, was rebuilt in brick on the original site in the 17th century after it was severely damaged in the civil wars.

Both St Mary’s and St Peter’s have good websites, which can be reached through the Southwell Diocesan website: http://southwellchurches.nottingham.ac.uk.

Little now remains of the Norman castle, although standing stone remains can be seen in the grounds of the current building, and the gatehouse is 13th century origin although extensively rebuilt in the 19th century. The Ducal Mansion on the castle site today was built by the 1st and 2nd Dukes of Newcastle from the 1650s. It is grade I listed.

For information on the castle see the items listed in Brook, Bibliography, 95-7. Also:

- Trevor Foulds, ‘”This Greate House, so lately begun, and all of freestone”: William Cavendish’s Italianate Palazzo called Nottingham Castle’, Transactions of the Thoroton Society, 106 (2002), 81-102

- Trevor Foulds, ‘”Old Road into the Park”: Nottingham Castle, Standard Hill and William Stretton’, Transactions of the Thoroton Society, 108 (2004)

- Gavin Kinsley, ‘Recent archaeological work on the Medieval Castle at Nottingham’, Transactions of the Thoroton Society, 107 (2003), 83-94

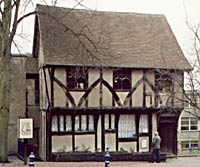

The 15th century Severns building is now on Castle Road; it was originally sited on Middle Pavement but was dismantled and moved in the late 1960s.

Few medieval domestic buildings have survived, although the Severns building, moved in 1970 to its present location outside the castle, dates from the 1430s. The Bell and Salutation public houses have fifteenth century timbers.

Few if any other timber-framed buildings have survived, but from the mid-seventeenth century the town has a good heritage, including Newdigate House on Castle Gate, of 1670, and other houses in this area. The rebuilding of Nottingham may have slowed down towards the end of the seventeenth century, although the buildings in Brewhouse Yard date from about 1700.

The urban renaissance of the late 17th and early 18th centuries brought with it a rebuilding and refashioning of the townscape in brick. There was also a slight change of fashion towards the more restrained and less ornamental style known as Palladian or Early Georgian, which can still be seen at Willoughby House on Low Pavement. Perhaps the best surviving example of this phase of building was Bromley House in the Old Market Square, completed in 1752.

The results of this architectural revolution are magnificently depicted on the splendid views of the market place drawn in the 1740s by Thomas Sandby, now in the Art Gallery collection at the Castle. Sandby showed only the frontages, but many houses had formal gardens, and small orchards. A number of householders on High and Low Pavements created vistas, or viewpoints over the surrounding countryside by maintaining a garden between their house and the cliff edge.

Public buildings from this period have generally been replaced, including the 1720s Exchange Building in the market place and the 1740s Guildhall at Weekday Cross. The 1770s county hall on High Pavement survives, and is now the Galleries of Justice.

Most of the poorer quality working class housing built between the 1770s and 1830s was swept away in the post-1920 slum clearance programmes. A handful of surviving houses on Lincoln Street have been converted into modern residences, but the small scale of these three-storey properties still gives an idea of the type of house once commonly found in the Broad Marsh area and around the eastern side of the town.

Nottingham was extensively developed in the nineteenth century. Middle class housing can be seen in the Wellington Square area, opened up from the 1840s, and the Park estate (largely designed by T.C. Hine, and built from the 1850s onwards). The huge warehouses which dominate the Lace Market area (many by Hine, and Watson Fothergill) date largely from the 1850s, and dominate the area around St Mary’s church.

A few examples of nineteenth century municipal housing survive, including Park View Flats, Bath Street, and Minitts Folly.

On the other hand, Nottingham has few industrial buildings per se, because hosiery manufacture largely took place in the home until the 1850s. the factory phase, as with lace production, was mainly located in the industrial villages including New Basford, New Radford and New Lenton, where a number of early factories and warehouses survive. These areas became part of the town in 1877.

The Guildhall.

The most notable civic building of the century was the Guildhall of 1876. For other public buildings see the entries listed in Brook, Bibliography, 97-8.

During the century a significant number of Anglican churches and nonconformist chapels were built in the town. Most of the Anglican churches have subsequently been demolished, but All Saints’, Raleigh Street, and St Saviour’s, in the Meadows, both of which were built in the 1860s outside of the main area of development, have survived. Other surviving Victorian churches, originally in surrounding parishes but now part of the conurbation, include Holy Trinity, Lenton (1842), St John’s Carrington (1844), and St Stephen, Hyson Green (1898).

Nonconformist chapels in the town have either been demolished or converted to other uses. The latter include the former Wesleyan chapel which is now the Broadway Cinema on George Street, and the Unitarian chapel (1876) on High Pavement, now the Pitcher and Piano public house.

The most distinguished nineteenth century church in the town is the Roman Catholic Cathedral on Derby Road, St Barnabas’s, by A.W.W. Pugin (1844). See Martin Cummins, Nottingham Cathedral: A History of Catholic Nottingham (3rd ed., Nottingham, 1994).

Towards the end of the century, the needs of primary education led to the creation of a school board and the building of a number of new schools. Among those surviving are Berridge Road School in Hyson Green, and Radford Board School on Lenton Boulevard.

In the twentieth century a further phase of building and redevelopment has seen a significant change in the city townscape. The most notable new civic building was the Council House, built by Cecil Howitt and opened by the Prince of Wales in 1929. It was erected on the site of the eighteenth century Exchange Building. See John Beckett and Ken Brand, The Council House Nottingham and Old Market Square (Nottingham, 2004)

Other public buildings of note include the University of Nottingham’s Highfields campus, and more recently its Jubilee campus by Sir Michael Hopkins, the University Hospital opened in 1970, and the Inland Revenue building (also by Hopkins). Articles about all these buildings can be found in successive editions of the Nottingham Civic Society Newsletter, available in Nottingham Local Studies Library on Angel Row.

The town centre has been largely redeveloped since 1900, and has become the commercial heart of the city as a result. The poorer quality housing of the marsh areas has been redeveloped since c.1920, and retail space such as the Broad Marsh has replaced the older housing areas. In turn, many of the families originally housed in these areas have moved out to the post-1920s council estates scattered around the western and northern edges of the city on land acquired through compulsory purchase and other deals, and through extensions in 1933 and 1951. On twentieth century development the best source is the newsletters of the Nottingham Civic Society from 1960 onwards.

Also in the new areas of development are to be found churches and schools, built to service the communities, together with leisure centres and smaller shopping areas. Some of these areas have a life of their own, closely guarded by their communities, but some places, as with St Ann’s and the Meadows, both areas of 1960s redevelopment, have acquired reputations for drug dealing and crime.

Ruins and Earthworks

In the development of the town during the 20th century most archaeological sites have been investigated and back filled. Some outer sections of the medieval castle have survived despite the 17th century rebuilding of the main structure: see Christopher Drage, Nottingham Castle: A Place Full Royal (Nottingham, 2nd edn., 1999).

Unlike Newark, Nottingham has no civil war fortifications, and nothing survives of the medieval town wall beyond a few stones in Brewhouse Yard museum. For a list of publications relating to the wall and Nottingham’s defences more generally see Brook, Bibliography, 97.

Archaeology

Archaeological excavation at Weekday Cross, 2005.

Although a great deal of archaeological research has been undertaken in Nottingham, little of it has been written up, although many of the artefacts can be seen in Brewhouse Yard museum.

For a discussion of the town’s pre-industrial archaeology see

- Young, C. S. B. 'Archaeology in Nottingham - The Pre-Conquest Borough', in Mastoris, S. N. and Groves, S. M., ed., History in the Making, 1985 (Nottingham Museums, 1986), 1-4

- Young, C. S. B. Discovering Rescue Archaeology in Nottingham. Nottingham City Council Museums, [1983?]

- MacCormick, A. G. 'Recent Archaeological Work in Nottingham', TTS, 80 (1976), [80]-81.

- MacCormick, A. G. 'Recent Archaeological Work in Nottingham', TTS, 82 (1978), [74]-75

- Alan MacCormick, ‘Nottingham’s underground maltings and other medieval caves: architecture and dating’, Transactions of the Thoroton Society, 105 (2001), 73-100

- Vicki Nailor, ‘Some Nottingham Medieval Pottery Wasters’, Transactions of the Thoroton Society, 104 (2000), 47-50

More recent excavations are usually noted briefly in Transactions of the Thoroton Society.

On Nottingham’s industrial archaeology see

- Morley, D. S. 'The Industrial Archaeology of the City of Nottingham', Nottingham Industrial Archaeology Society Journal, 11, 2 (1986), 1-20

Nothing has survived of the medieval hospital and other non-church ecclesiastical buildings.